Swahili language

| Swahili Kiswahili | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spoken in: | ||

| Total speakers: | First language: 5-10 million Second language: 80 million[1] | |

| Language family: | Niger-Congo Atlantic-Congo Volta-Congo Benue-Congo Bantoid Southern Narrow Bantu Central G Swahili | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language of: | ||

| Regulated by: | Baraza la Kiswahili la Taifa (Tanzania) | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | sw | |

| ISO 639-2: | swa | |

| ISO 639-3: | variously: swa — Swahili (generic) swc — Congo Swahili swh — Swahili (specific) | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Swahili (also called Kiswahili; see below for derivation) is a Bantu language of the Sabaki subgroup of Northeastern Coast Bantu languages. Swahili is the mother tongue of the Swahili people (or Waswahili) who inhabit several large stretches of the Indian Ocean coastlines from southern Somalia as far south as Mozambique's border region with Tanzania.[2] Although only 5-10 million people speak it as their native language,[1] it is spoken as a second language by around 80 million people in Southeast African lingua franca, making it the most widely spoken language of sub-Saharan Africa. It is now the only African language among the official working languages of the African Union. Swahili is also taught in the major universities in the world, and several international media outlets, such as the BBC, Voice of America, and Xinhua, have Swahili programs.

In common with all Bantu languages, Swahili grammar arranges nouns into a number of classes according to their usage. Swahili verbs consist of a root and a number of affixes (mostly prefixes) which can be attached to express grammatical persons, tense and many clauses that would require a conjunction in other languages (usually prefixes).

Overview

Swahili, spoken natively by various groups traditionally inhabiting about 1,500 miles of the East African coastline, has become a second language spoken by tens of millions in three countries, Tanzania, Kenya, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where it is an official national language. The neighboring nation of Uganda made Swahili a required subject in primary schools in 1992—although this mandate has not been well implemented—and declared it an official language in 2005. Swahili, or another closely related language, is also used by relatively small numbers of people in Burundi, Rwanda, Mozambique, Somalia, and Zambia, and nearly the entire population of the Comoros.

Swahili is a Bantu language of the Sabaki subgroup of Northeastern Coast Bantu languages. It is most immediately related to the Kenyan Bantu languages of Ilwana, Pokomo, and Mijikenda (Digo, Giryama, Duruma, and so on), which are spoken in the Kenya coastal hinterland, and to Comorian (Ngazija, Nzuani, Mwali, and Maore) of the Comoro Islands. Other members of the group include Chimwiini of Barawa, Somalia, and Mwani of the Kerimba Islands and northern coastal Mozambique. Many second language speakers of Swahili are native speakers of another Bantu language, or of a Nilotic or Cushitic language.

In the Guthrie nongenetic classification of Bantu languages, Swahili is included under Bantoid/Southern/Narrow Bantu/Central/G.

One of the earliest known documents in Swahili, dated 1728, is an epic poem in the Arabic script titled Utendi wa Tambuka (The History of Tambuka). Under the influence of European colonial powers, the Latin alphabet became standard for written Swahili.

Name

The name "Kiswahili" comes from the plural of the Arabic word sahel ساحل: sawahil سواحل meaning "boundary" or "coast" (used as an adjective to mean "coastal dwellers" or, by adding 'ki-' ["language"] to mean "coastal language"). (The word "sahel" is also used for the border zone of the Sahara ("desert")). The incorporation of the final "i" is likely to be the nisba in Arabic (of the coast سواحلي), although some believe it is added for phonetic reasons.

"Ki-" is a prefix attached to nouns of the noun class that includes languages (see Noun classes below). Kiswahili refers to the "Swahili Language;" Waswahili refers to the people of the "Swahili Coast;" and Uswahili refers to the "Culture" of the Swahili People.

The Rise of Swahili to Regional Prominence[3]

There is as yet insufficient historical or archaeological evidence to establish, with confidence, when and where either the Swahili language or the Swahili ethnicity emerged. Nevertheless, it is assumed that the Swahili speaking people have occupied their present territories, hugging the Indian Ocean, since well before 1000 C.E.. Arab invaders from the Oman conquered and Islamicized much of the Swahili territories, in particular the twin islands of Zanzibar and Pemba to the south and the port towns to the north,such as Mombasa. Historically, Swahili literature first flowered in the northern half, though today Zanzibar is considered the center of Swahili culture.

Starting about 1800, the rulers of Zanzibar organized trading expeditions into the interior of the mainland, up to the various lakes in the continent's Great Rift Valley. They soon established permanent trade routes and Swahili-speaking merchants settled in villages along the new trade routes. Generally, this process did not lead to genuine colonization except for in the area west of Lake Malawi, in what is now Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a highly divergent dialect arose. However, trade and migration helped spread the Swahili dialect of Zanzibar Town (Kiunguja) to the interior of Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Rebublic, and Mozambique. Later, Christian missionaries learned Swahili as the language of communication to spread the Gospel in Eastern Africa and spread the language through their schools and publications. The first Swahili-English dictionary was prepared by a missionary,[4] and the first Swahili newspaper, Habari ya Mwezi, was published by missionaries in 1895.[5]

After Germany seized the region known as Tanganyika (present day mainland Tanzania) as a colony in 1886, it took notice of the wide (but shallow) dissemination of Swahili, and soon designated Swahili as an official administrative language. The British did not follow suit in neighboring Kenya, though they made moves in that direction. The British and Germans were both anxious to facilitate their rule over colonies where dozens of languages were spoken, by selecting a single local language that could be well accepted by the natives. Swahili was the only possible candidate.

In the aftermath of Germany's defeat in World War I, it was dispossessed of all its overseas territories. Tanganyika fell into British hands. The British authorities, with the collaboration of British Christian missionary institutions active in these colonies, increased their resolve to institute Swahili as a common language for primary education and low-level governance throughout their East African colonies (Uganda, Tanganyika, Zanzibar, and Kenya). Swahili was to be subordinate to English: university education, much secondary education, and governance at the highest levels would be conducted in English.

In order to establish Swahili as an official language it was necessary to create a standard written language. In June 1928, an interterritorial conference was held at Mombasa, at which the Zanzibar dialect, Kiunguja, was chosen to be the basis for standardizing Swahili.[6] The version of standard Swahili taught today as a second language, is for practical purposes Zanzibar Swahili, though there are minor discrepancies between the written standard and the Zanzibar vernacular.

Foreign loan words

A thousand years of contact between Indian Ocean peoples and Swahili resulted in a large number of borrowed words entering the language, mainly from Arabic, but also from other languages such as Persian and various Indian languages. At different periods Swahili also borrowed vocabulary from Portuguese and English. The proportion of such borrowed words is comparable to the proportion of French, Latin, and Greek loans used in English. Although the proportion of Arabic loans may be as high as fifty percent in classical Swahili poetry (traditionally written in Arabic script), it amounts to less than twenty percent of the lexicon of the spoken language.[7]

Swahili language

Sounds

Swahili is unusual among sub-Saharan languages in having lost the feature of lexical tone (with the exception of the Mijikenda dialect group that includes the numerically important Mvita dialect, the dialect of Kenya's second city, the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa).

Vowels

Standard Swahili has five vowel phonemes: /ɑ/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/, and /u/. They are very similar to the vowels of Spanish and Italian, though /u/ stands between /u/ and /o/ in those languages. Vowels are never reduced, regardless of stress. The vowels are pronounced as follows:

- /ɑ/ is pronounced like the "a" in father

- /ɛ/ is pronounced like the "e" in bed

- /i/ is pronounced like the "i" in ski

- /ɔ/ is pronounced like the first part of the "o" in American English home, or like a tenser version of "o" in British English "lot"

- /u/ is pronounced between the "u" in rude and the "o" in rote.

Swahili has no diphthongs; in vowel combinations, each vowel is pronounced separately. Therefore the Swahili word for "leopard," chui, is pronounced /tʃu.i/, with hiatus.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

| Nasal stop | m /m/ | n /n/ | ny /ɲ/ | ng’ /ŋ/ | ||||

| Prenasalized stop | mb /mb/ | nd /nd/ | nj /ɲɟ/~/ndʒ/ | ng /ŋɡ/ | ||||

| Implosive stop | b /ɓ/ | d /ɗ/ | j /ʄ/ | g /ɠ/ | ||||

| Tenuis stop | p /p/ | t /t/ | ch /tʃ/ | k /k/ | ||||

| Aspirated stop | p /pʰ/ | t /tʰ/ | ch /tʃʰ/ | k /kʰ/ | ||||

| Prenasalized fricative | mv /ɱv/ | nz /nz/ | ||||||

| Voiced fricative | v /v/ | (dh /ð/) | z /z/ | (gh /ɣ/) | ||||

| Voiceless fricative | f /f/ | (th /θ/) | s /s/ | sh /ʃ/ | (kh /x/) | h /h/ | ||

| Trill | r /r/ | |||||||

| Lateral approximant | l /l/ | |||||||

| Approximant | y /j/ | w /w/ |

Notes:

- The nasal stops are pronounced as separate syllables when they appear before a plosive (mtoto [m.to.to] "child," nilimpiga [ni.li.m.pi.ɠa] "I hit him"), and prenasalized stops are decomposed into two syllables when the word would otherwise have one (mbwa [m.bwa] "dog"). However, elsewhere this doesn't happen: ndizi "banana" has two syllables, [ndi.zi], as does nenda [ne.nda] (not *[nen.da]) "go."

- The fricatives in parentheses, th dh kh gh, are borrowed from Arabic. Many Swahili speakers pronounce them as [s z h r], respectively.

- Swahili orthography does not distinguish aspirate from tenuis consonants. When nouns in the N-class begin with plosives, they are aspirated (tembo [tembo] "palm wine," but tembo [tʰembo] "elephant") in some dialects. Otherwise aspirate consonants are not common.

- Swahili l and r are confounded by many speakers, and are often both realized as /ɺ/

Noun classes

In common with all Bantu languages, Swahili grammar arranges nouns into a number of classes. The ancestral system had twenty-two classes, counting singular and plural as distinct according to the Meinhof system, with most Bantu languages sharing at least ten of these. Swahili employs sixteen: Six classes that usually indicate singular nouns, five classes that usually indicate plural nouns, a class for abstract nouns, a class for verbal infinitives used as nouns, and three classes to indicate location.

| class | nominal prefix |

example | translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m- | mtu | person |

| 2 | wa- | watu | persons |

| 3 | m- | mti | tree |

| 4 | mi- | miti | trees |

| 5 | Ø/ji- | jicho | eye |

| 6 | ma- | macho | eyes |

| 7 | ki- | kisu | knife |

| 8 | vi- | visu | knives |

| 9 | Ø/n- | ndoto | dream |

| 10 | Ø/n- | ndoto | dreams |

| 11 | u- | uani | backyard |

| 14 | u- | utoto | childhood |

Nouns beginning with m- in the singular and wa- in the plural denote animate beings, especially people. Examples are mtu, meaning "person" (plural watu), and mdudu, meaning "insect" (plural wadudu). A class with m- in the singular but mi- in the plural often denotes plants, such as mti "tree," miti trees. The infinitive of verbs begins with ku-, for example, kusoma "to read." Other classes are harder to categorize. Singulars beginning in ki- take plurals in vi-; they often refer to hand tools and other artifacts. This ki-/vi- alteration even applies to foreign words where the ki- was originally part of the root, so vitabu "books" from kitabu "book" (from Arabic kitāb "book"). This class also contains languages (such as the name of the language Kiswahili), and diminutives, which had been a separate class in earlier stages of Bantu. Words beginning with u- are often abstract, with no plural, for example, utoto "childhood."

A fifth class begins with n- or m- or nothing, and its plural is the same. Another class has ji- or no prefix in the singular, and takes ma- in the plural; this class is often used for augmentatives. When the noun itself does not make clear which class it belongs to, its concords do. Adjectives and numerals commonly take the noun prefixes, and verbs take a different set of prefixes.

| singular | plural | |||||

| mtoto | mmoja | anasoma | watoto | wawili | wanasoma | |

| child | one | is reading | children | two | are reading | |

| One child is reading | Two children are reading | |||||

| kitabu | kimoja | kinatosha | vitabu | viwili | vinatosha | |

| book | one | suffices | books | two | suffice | |

| One book is enough | Two books are enough | |||||

| ndizi | moja | inatosha | ndizi | mbili | zinatosha | |

| banana | one | suffices | bananas | two | suffice | |

| One banana is enough | Two bananas are enough | |||||

The same noun root can be used with different noun-class prefixes for derived meanings: Human mtoto (watoto) "child (children)," abstract utoto "childhood," diminutive kitoto (vitoto) "infant(s)," augmentative toto (matoto) "big child (children)." Also vegetative mti (miti) "tree(s)," artifact kiti (viti) "stool(s)," augmentative jiti (majiti) "large tree," kijiti (vijiti) "stick(s)," ujiti (njiti) "tall slender tree."

Although the Swahili noun class system is technically grammatical gender, there is a difference from the grammatical gender of European languages; in Swahili, the class assignments of nouns is still largely semantically motivated, whereas the European systems are mostly arbitrary. However, the classes cannot be understood as simplistic categories such as "people" or "trees." Rather, there are extensions of meaning, words similar to those extensions, and then extensions again from these. The end result is a semantic net that made sense at the time, and often still does make sense, but which can be confusing to a non-speaker.

For example, the ki-/vi- class was originally two separate genders: artifacts (Bantu class 7/8, utensils & hand tools mostly) and diminutives (Bantu class 12). Examples of the first are kisu "knife;" kiti "chair, stool," from mti "tree, wood;" chombo "vessel" (a contraction of ki-ombo). Examples of the latter are kitoto "infant," from mtoto "child;" kitawi "frond," from tawi "branch;" and chumba (ki-umba) "room," from nyumba "house." It is the diminutive sense that has been furthest extended. An extension common to many languages is approximation and resemblance (having a 'little bit' of some characteristic, like -y or -ish in English). For example, there is kijani "green," from jani "leaf" (compare English "leafy"), kichaka "bush" from chaka "clump," and kivuli "shadow" from uvuli "shade." A "little bit" of a verb would be an instance of an action, and such instantiations (usually not very active ones) are also found: Kifo "death," from the verb -fa "to die;" kiota "nest" from -ota "to brood;" chakula "food" from kula "to eat;" kivuko "a ford, a pass" from -vuka "to cross;" and kilimia "the Pleiades, from -limia "to farm with," from its role in guiding planting. A resemblance, or being a bit like something, implies marginal status in a category, so things that are marginal examples of their class may take the ki-/vi- prefixes. One example is chura (ki-ura) "frog," which is only half terrestrial and therefore marginal as an animal. This extension may account for disabilities as well: Kilema "a cripple," kipofu "a blind person," kiziwi "a deaf person." Finally, diminutives often denote contempt, and contempt is sometimes expressed against things that are dangerous. This might be the historical explanation for kifaru "rhinoceros," kingugwa "spotted hyena," and kiboko "hippopotamus" (perhaps originally meaning "stubby legs").

Another class with broad semantic extension is the m-/mi- class (Bantu classes 3/4). This is often called the 'tree' class, because mti, miti "tree(s)" is the prototypical example, but the class encompasses much broader meaning. It seems to cover vital entities which are neither human nor typical animals: Trees and other plants, such as mwitu "forest" and mtama "millet" (and from there, things made from plants, like mkeka "mat"); supernatural and natural forces, such as mwezi "moon," mlima "mountain," mto "river;" active things, such as moto "fire," including active body parts (moyo "heart," mkono "hand, arm"); and human groups, which are vital but not themselves human, such as mji "village," perhaps msikiti "mosque," and, by analogy, mzinga "beehive." From the central idea of tree, which is thin, tall, and spreading, comes an extension to other long or extended things or parts of things, such as mwavuli "umbrella," moshi "smoke," msumari "nail;" and from activity there even come active instantiations of verbs, such as mfuo "hammering," from -fua "to hammer," or mlio "a sound," from -lia "to make a sound." Words may be connected to their class by more than one metaphor. For example, mkono is an active body part, and mto is an active natural force, but they are also both long and thin. Things with a trajectory, such as mpaka "border" and mwendo "journey," are classified with long thin things in many languages. This may be further extended to anything dealing with time, such as mwaka "year" and perhaps mshahara "wages." Also, animals which are exceptional in some way and therefore don't fit easily in the other classes may be placed in this class.

The other classes have foundations that may at first seem similarly counter intuitive.[8]

Verb affixation

Swahili verbs consist of a root and a number of affixes (mostly prefixes) which can be attached to express grammatical persons, tense and many clauses that would require a conjunction in other languages (usually prefixes). As sometimes these affixes are sandwiched in between the root word and other affixes, some linguists have mistakenly assumed that Swahili uses infixes which is not the case.

Most verbs, the verbs of Bantu origin, will end in "-a." This is vital to know for using the Imperative, or Command, conjugation form.

In most dictionaries, verbs are listed in their root form, for example -kata meaning "to cut/chop." In a simple sentence, prefixes for grammatical tense and person are added, for example, ninakata. Here ni- means "I" and na- indicates present tense unless stated otherwise.

Verb Conjugation

ni- -na- kata 1sg DEF. TIME cut/chop

- "I am cutting (it)"

Now this sentence can be modified either by changing the subject prefix or the tense prefix, for example:

u- -na- kata 2sg DEF. TIME cut/chop

- "You are cutting"

u- -me- kata 2sg PERFECT cut/chop

- "You have cut"

The simple present is more complicated and learners often take some of the phrases for slang before they discover the proper usage. Nasoma means "I read." This is not short for ninasoma ("I am reading"). -A- is the indefinite (gnomic tense) prefix, used for example in generic statements such as "birds fly," and the vowel of the prefix ni- is assimilated. It may be simpler to consider these to be a single prefix:

| 1st PERSON | na- | twa- |

| 2nd PERSON | wa- | mwa- |

| 3rd PERSON | a- | wa- |

na- soma 1sg:GNOM read

- "I read"

mwa- soma 2pl:GNOM read

- "You (pl) read"

The complete list of basic subject prefixes is (for the m-/wa- or human class):

SINGULAR PLURAL 1st PERSON Ni- Tu- 2nd PERSON U- M- 3rd PERSON A- Wa-

The most common tense prefixes are:

a- gnomic (indefinite time) na- definite time (often present progressive) me- perfect li- past ta- future hu- habitual

“Tense prefixes” are not only used to express tenses, in the sense used in the English language, but also to articulate conjunctions. For example ki- is the prefix for <conditional>—the sentence, "nikinunua nyama wa mbuzi sokoni, nitapika leo," means "If I buy goat meat at the market, I'll cook today." The conjunction "if" in this sentence is simply represented by -ki.

A third prefix can be added, the object prefix. It is placed just before the root and can either refer to a person, replace an object or emphasize a particular one, for example:

a- na- mw- ona 3sg DEF.T. 3sg.OBJ see

- "He (is) see(ing) him/her"

ni- na- mw- ona mtoto 1sg DEF.T. 3sg.OBJ see child

- "I (am) see(ing) the child"

Suffixes are also used. The “root” of words as given in most Swahili dictionaries is not the true root; the final vowel is also an affix. The suffix “a” on the root words provided by Swahili dictionaries indicates the indicative form of each word. Other forms also occur; for instance, with negation: In the word. sisomi (the "-" it represents an empty space and means null morpheme):

si- - som- -i 1sg.NEG TENSE read NEG

- "I am not reading/I don't read"

Other instances of this change of the final vowel include the conjunctive, where an -e is implemented. This rule is true only for Bantu verbs ending with -a; ones derived from Arabic follow more complex rules.

Other suffixes, which once again look suspiciously like infixes, are placed before the end vowel, such as

wa- na- pig -w -a 3pl DEF.T. hit PASSIVE IND.

- "They are being hit"

Swahili time

(East African) Swahili time runs from dawn (at six a.m.) to dusk (at six p.m.), rather than midnight to midday. Seven a.m. and seven p.m. are therefore both “one o'clock,” while midnight and midday are “six o'clock.” Words such as asubuhi "morning," jioni "evening," and usiku "night" can be used to demarcate periods of the day, for example:

- saa moja asubuhi ("hour one morning") 7:00 a.m.

- saa tisa usiku ("hour nine night") 3:00 a.m.

- saa mbili usiku ("hour two evening") 8:00 p.m.

More specific time demarcations include adhuhuri "early afternoon," alasiri "late afternoon," usiku wa manane "late night/past midnight," "sunrise" macheo, and "sunset" machweo.

At certain times there is some overlap of terms used to demarcate day and night; 7:00 p.m. can be either saa moja jioni or saa moja usiku.

Other relevant phrases include na robo "and a quarter," na nusu "and a half," kasarobo/kasorobo "less a quarter," and dakika "minute(s):"

- saa nne na nusu ("hour four and a half") 10:30

- saa tatu na dakika tano ("hour three and minutes five") five past nine

- saa mbili kasorobo ("hour two less a quarter") 7:45

- saa tatu kasoro ("a few minutes to nine")

Swahili time derives from the fact that the sun rises at around six a.m. and sets at around six p.m. everyday in the equatorial regions where most Swahili speakers reside.

Dialects of Swahili

Modern standard Swahili is based on Kiunguja, the dialect spoken in Zanzibar town.

There are numerous local dialects of Swahili, including the following.[10]

- Kiunguja: Spoken in Zanzibar town and environs on Zanzibar island. Other dialects occupy the bulk of the island.

- Kitumbatu and Kimakunduchi: The countryside dialects of the island of Zanzibar. Kimakunduchi is a recent renaming of "Kihadimu;" the old name means "serf," hence it is considered pejorative.

- Kimrima: Spoken around Pangani, Vanga, Dar es Salaam, Rufiji, and Mafia Island.

- Kimgao: Formerly spoken around Kilwa and to the south.

- Kipemba: Local dialect of the island of Pemba.

- Mijikenda, a group of dialects spoken in and around Mvita island. Includes Kimvita, the other major dialect alongside Kiunguja.

- Kingare: Subdialect of the Mombasa area.

- Chijomvu: Subdialect of the Mombasa area.

- Chi-Chifundi: Dialect of the southern Kenya coast.

- Kivumba: Dialect of the southern Kenya coast.

- Kiamu: Spoken in and around the island of Lamu (Amu).

- Sheng: A sort of street slang, this is a blend of Swahili, English, and some ethnic languages spoken in and around Nairobi in informal settings. Sheng originated in the Nairobi slums and is considered fashionable and cosmopolitan among a growing segment of the population.

Languages similar to Swahili

- Kimwani: Spoken in the Kerimba Islands and northern coastal Mozambique.

- Kingwana: Spoken in the eastern and southern regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sometimes called Copperbelt Swahili, especially the variety spoken in the south.

- Comorian language, the language of the Comoros Islands, which form a chain between Tanzania and the northern tip of Madagascar.

- Chimwiini was traditionally spoken around the Somali town of Barawa. In recent years, most of its speakers have fled to Kenya to escape civil war. Linguists specializing in Swahili, Chimwiini speakers, and speakers of other Swahili dialects all debate whether Chimwiini is Swahili or a distinct language.

Current usage of Swahili

At the present time, some 90 percent of approximately 39 million Tanzanians speak Swahili.[11] Kenya's population is comparable, but the prevalence of Swahili is lower, though still widespread. The five eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (to be subdivided in 2009) are Swahili speaking. Nearly half the 66 million Congolese speak it;[12] and it is starting to rival Lingala as the most important national language of that country. In Uganda, the Baganda generally don't speak Swahili, but it is in common use among the 25 million people elsewhere in the country, and is currently being implemented in schools nationwide in preparation for the East African Community. The usage of Swahili in other countries is commonly overstated, being common only in market towns, among returning refugees, or near the borders of Kenya and Tanzania. Even so, Swahili possibly exceeds Hausa of West Africa as the sub-Saharan indigenous language with the greatest number of speakers, who may number some ten to fifteen percent of the 750 million people of sub-Saharan Africa.[13]

Swahili literature

The first literary works in Swahili date back to the beginning of the eighteenth century, when all Swahili literature was written in the Arabic script. Jan Knappert considered the translation of Arabic poem Hamziya from the year 1652 to be the earliest Swahili written text. Starting in the nineteenth century, Christian missionaries and orientalists introduced the Roman alphabet for recording Swahili language.

During the nineteeth century, western scholars began to study Swahili literature, and a few of them tried to establish a canon of Swahili writing.[14] Because of this orientalist exploration and interest in the Swahili culture and language, it much of the analysis and commentary on Swahili literature has been done outside of its place of origin.

One of the main characteristics of the Swahili literature is the relative heterogeneity of the Swahili language. Works are written in Kiamu, Kimvita, Kipemba, Kiunguja, Kimrima, Kimtang'ata, Ki-Dar-es-salaam and Ki-Nairobi.[15]

Swahili literature has sometimes been characterized as Islamic by western scholars such as Jan Knappert, but others such as Alamin Mazrui and Ibrahim Noor Shariff[16] point out that Swahili poetry includes many secular works by such poets as Muyaka bin Ghassany and Muhammad Kijuma.[17]

Swahili literature is classified into three genres: Riwaya (the novel), tamthilia (drama) and shairi (from Arabic: Shîir, poetry). Fiction in Swahili literature mainly consisted of oral narrative traditions; it was not until the 1940s that Swahili began to have a written fiction. At first, written fiction consisted mostly of stories inspired by indigenous oral narrative traditions, Arabic tales, and translations of works by European writers. An important exception was James Mbotela's 1934 historical novel Uhuru wa Watumwa (Freedom for the Slaves).

Swahili poetry or "shairi" is generally derived from Arabic poetry and is still written in the traditional manner. It began in the northern Kenya coastal towns of Lamu and Pate before spreading to Tanga Region, Zanzibar and other nearby areas.[18] There are, however, fundamental differences between the Arabic poetry and Swahili poetry, which arises from the experiences of life on the African subcontinent. [19] Traditional poetry can be classified into different groups, epic, lyrical, or didactic, according to its form and content; it can be further classified as religious or secular.[20] Examples of narrative poetry, known as utenzi, include the Utendi wa Tambuka by Bwana Mwengo (dated to about 1728) and the Utenzi wa Shufaka.

Until recently, Swahili prose was restricted to practical uses such as the dissemination of information or the recording of events. However, the traditional art of oral expression, characterized by its homiletic aspects, heroic songs, folklore ballads and humorous dialogues which accurately depict Swahili life, cultural beliefs and traditions, has produced a number of valuable works.

Shaaban Robert (1909–62), a Tanganyikan poet, novelist, and essayist, wrote works in the new Standard Swahili that gained wide circulation in the 1940s, '50s, and '60s and are highly esteemed in East Africa today. Another important writer from this period was the Zanzibari Muhammed Saleh Farsy, whose novel Kurwa na Doto (1960; “Kurwa and Doto”) is a minor classic. Muhammed Said Abdulla, another Zanzibari, wrote a series of detective adventures, the first of which, Mzimu wa Watu wa Kale (1960; “Shrine of the Ancestors”), marked the beginning of a Swahili fiction reflecting the modern East African experience of industrialization, westernization, the struggle for self-government and the development of post-independence society. Tanzanian Faraji Katalambulla published a successful modern crime thriller, Simu ya Kifo (Death Call), in 1965, after which the volume of works published in Swahili grew dramatically.

Romances, detective fiction, and traditional tales continue to be the mainstay of the literature, but there are several novels and plays that examine historical events and contemporary social and political problems in a sophisticated and stylistically elegant manner. Swahili-language translations now also include works by African as well as Western writers. Authors who have received local and international acclaim include the novelists

Notable literary people

- Farouk Topan—Tanzania

- Ebrahim Hussein (1943- ) Tanzania

- Muhammed Said Abdulla (April 25, 1918) Tanzania

- Pera Ridhiwani (1917-1997) Tanzania

- May M Balisidya (?-1987), Tanzania

- Mzee Hamis Akida (November 22, 1914- ), Tanzania

- Said Khamis (December 12, 1947-), Zanzibar

- Abdilatif Abdalla (April 14, 1946-), Kenya

- Euphrase Kezilahabi (April 13, 1944- ), Tanzania

- Mohammed S. Mohammed (1945- ), Tanzania

- Ebrahim Hussein (1943- ), Tanzania

- Penina O. Muhando (1948- ), Tanzania

- Ali Jemaadar Amir, Kenya

- Katama Mkangi (1944–2004), Kenya

- P.M. Kareithi, Kenya

Swahili in non-African popular culture

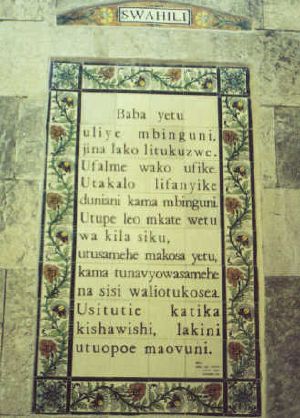

In Civilization IV, the title music is a rearrangement of the Lord's Prayer in Swahili, sharing the same name—"Baba Yetu" ("Our Father").

In Michael Jackson's 1987 single, "Liberian Girl," the repeated intro is the Swahili phrase "Nakupenda pia, nakutaka pia, mpenzi wee!" which translates "I love you too, and I want you too, my love!"

Disney's animated film The Lion King contains several Swahili references. "Simba," the main-character's name, means lion, "Rafiki" means friend, and the name of the popular song "Hakuna Matata" means "no problems."

Bungie Studios uses this language in some of its games (Halo 2).

Gene Roddenberry took the name of Lieutenant Uhura in Star Trek from the Swahili word Uhuru meaning "freedom."

Also, the word "Imzadi" used in Star Trek: The Next Generation has a derivative in Swahili. It means "beloved."

Swahili Literature

- Bertoncini-Zúbková, Elena. 1996. Vamps and Victims - Women in Modern Swahili Literature. An Anthology. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, pp. 134-137. ISBN 3-927620-74-2

- Bertoncini-Zúbková, Elena. 1989. Outline of Swahili Literature: Prose, Fiction and Drama. Brill, pp. 353. ISBN 90-04-08504-1

- Knappert, Jan. 1979. Four Centuries of Swahili Verse: A Literary History and Anthology. Heinemann, 333 p.. ISBN 0-435-91702-1

- Knappert, Jan. 1982. "Swahili oral traditions", in V. Görög-Karady (ed.) Genres, forms, meanings: essays in African oral literature, 22-30.

- Knappert, Jan. 1983. Epic poetry in Swahili and other African languages. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004068775 ISBN 9789004068773

- Knappert, Jan. 1990. A grammar of literary Swahili. (Working papers on Kiswahili, 10). Lewiston, N.Y. : E. Mellen Press. ISBN 0773478825 ISBN 9780773478824 ISBN 077347949X ISBN 9780773479494

- Nagy, Géza Füssi. The rise of Swahili literature and the œuvre of Shaaban bin Robert (Academic journal)

- Topan, Farous. 2006. Why Does a Swahili Writer Write? Euphoria, Pain, and Popular Aspirations in Swahili Literature (Academic journal) Research in African Literatures.

- Lodhi, Abdulaziz Y. and Lars Ahrenberg. 1985. Swahililitteratur - en kort šversikt. (Swahili literature: a short overview.) In: Nytt från Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, no 16, pp 18-21. Uppsala. (Reprinted in Habari, vol 18(3), 198-.)

- Ali A. Mazrui, Alamin M. Mazrui. 1999. The Political Culture of Language: Swahili, Society and the State (Studies on Global Africa). Binghamton, N.Y. : Institute of Global Culture Studies (IGCS), Binghamton University, the State University of New York. ISBN 1883058066 ISBN 9781883058067

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 L Marten, "Swahili," Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd ed., 2005, Elsevier Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "marten" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Prins (1961).

- ↑ Whiteley (1969); N&H (1993).

- ↑ UCLA, Swahili, Language Materials Project.

- ↑ Omniglot, Swahili (kiSwahili). Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ Whiteley (1969), 80.

- ↑ Omniglot, Swahili (kiSwahili). Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ Virginia University, Noun Classification in Swahili. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ N&H (1993).

- ↑ H.E. Lambert 1956, 1957, 1958.

- ↑ Brock-Utne (2001), 123.

- ↑ Mail & Guardian, DRC welcomes Swahili as an official AU language. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ World Bank, Sub-Saharan Africa Data Profile. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ Jan Knappert, The Canon of Swahili Literature (London: Middle East Studies and Libraries, 1980).

- ↑ Nordic Journal of African Studies, The Heterogeneity of Swahili Literature.

- ↑ Alamin Mazrui and Ibrahim Noor Shariff, The Swahili. Idiom and Identity of an African People, 95-97.

- ↑ Harriet Tubman Seminar, Islam, language and ethnicity in Eastern Africa: Some literary considerations. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- ↑ Ossrea, ossrea.net The Waswahili/Swahili Culture.7

- ↑ Lyndon Harries, Poetry provides a remarkable outlet for personal expression in Swahili culture. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ↑ Vessella, vessella.it Swahili. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashton, E. O. 1947. Swahili Grammar: Including Intonation. Essex: Longman House. ISBN 0-582-62701-X.

- Brock-Utne, Birgit. 2001. Education for all—in whose language? Oxford Review of Education 27(1): 115-134.

- Chiraghdin, Shihabuddin, and Mathias Mnyampala. 1977. Historia ya Kiswahili. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-572367-8.

- Contini-Morava, Ellen. 1994. Noun Classification in Swahili. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- Lambert, H.E. 1956. Chi-Chifundi: A Dialect of the Southern Kenya Coast.

- Lambert, H.E. 1957. Ki-Vumba: A Dialect of the Southern Kenya Coast.

- Lambert, H.E. 1958. Chi-Jomvu and ki-Ngare: Subdialects of the Mombasa Area.

- Marshad, Hassan A. 1993. Kiswahili au Kiingereza (Nchini Kenya). Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. ISBN 9966-22-098-4.

- Nurse, Derek, and Thomas J. Hinnebusch. 1993. Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History. Series: University of California Publications in Linguistics, v. 121.

- Prins, A.H.J. 1961. The Swahili-Speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and the East African Coast (Arabs, Shirazi and Swahili). Ethnographic Survey of Africa, edited by Daryll Forde. London: International African Institute.

- Prins, A.H.J. 1970. A Swahili Nautical Dictionary. Preliminary Studies in Swahili Lexicon - 1. Dar es Salaam.

- Whiteley, Wilfred. 1969. Swahili: The Rise of a National Language. London: Methuen.

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Omniglot's entry on the Swahili writing system.

- Swahili Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: Factors of Its Development and Expansion.

- Swahili educational and cultural Website.

- New Testament in Swahili.

Dictionaries:

Live Streams

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.