| Tai chi chuan (太極拳) | |

|---|---|

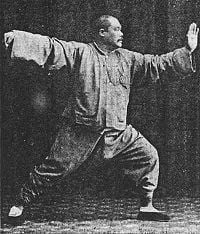

Yang Chengfu in a posture from the Yang style tai chi chuan solo form known as Single Whip c. 1931 | |

| Also known as | t'ai chi ch'üan; tai ji quan |

| Hardness | Forms competition, light-contact (no strikes), full contact (striking, kicking, etc.) |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Disputed |

| Parenthood | Tao Yin |

| Olympic Sport | No |

Tai chi chuan (Traditional Chinese: 太極拳; Simplified Chinese: 太极拳; Hanyu Pinyin: tài jí quán; Wade-Giles: t'ai4 chi2 ch'üan2) is an internal (neijia, Wudangquan) Chinese martial art, in which an aggressor's force and momentum is turned to his or her disadvantage through the use of “soft” techniques such as pushing, grappling, and open hand strikes. The least possible amount of force is exerted to “capture” the center of balance and bring an adversary under control. Tai chi training primarily involves learning solo routines, known as forms (套路, taolu), slow sequences of movements which emphasize a straight spine, abdominal breathing and a natural range of motion; and different styles of pushing hands (tui shou, 推手) martial arts techniques. Accurate, repeated practice of the solo routine improves posture, strengthens muscles, encourages circulation throughout the body, maintains flexibility of the joints and further familiarizes students with the martial application sequences implied by the forms.

The origins of tai chi chuan are known only through legend and speculation. The oldest documented tradition is that of the Chen family, dating from the 1820s.[1][2] Most modern styles of tai chi trace their development to at least one of the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu/Hao, Wu and Sun, all of which originated with the Chen family. Today, tai chi is practiced worldwide. Tai chi is practiced for a variety of reasons: its soft martial techniques, mind-body unity, training of sprituality, demonstration competitions, and promotion of health and longevity. A multitude of training forms, both traditional and modern, exists. Some of tai chi chuan's training forms are known to Westerners as the slow motion routines that groups of people practice together every morning in parks around the world, particularly in China.

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

Overview

| Part of the series on Chinese martial arts |

|

| List of Chinese martial arts |

|---|

| Terms |

|

| Historical places |

|

| Historical people |

|

| Related |

|

| view • talk |

The Mandarin term "t'ai chi ch'uan" literally translates as "supreme ultimate fist," "boundless fist," or "great extremes boxing" (note that 'chi' in this instance is an earlier romanization of modern 'ji,' not to be confused with the use of 'chi' in the sense of 'life-force' or 'energy', which is an earlier romanization of modern 'qi'). The word "quan" translates to English as "boxing" or "fist." The pinyin standard spells it "quan;" the Wade-Giles standard spells it "ch'uan." The concept of the "supreme ultimate" appears in both Daoist and Confucian Chinese philosophy where it represents the fusion [3] of Yin and Yang into an ultimate whole represented by the taijitu symbol (t'ai chi t'u, 太極圖), commonly known in the West as the "yin-yang" diagram. Tai chi theory and practice evolved in agreement with many of the principles of Chinese philosophy including both Daoism and Confucianism.

Tai chi chuan was classified by Sun Lutang in the 1920s as Wudangquan, a neijia (internal) Chinese martial art along with Xíngyìquán and Bāguàzhǎng. Most other martial arts are classified as "wàijiā" (lit. "external/outside sect"). It is considered a soft style martial art—an art applied with internal power—to distinguish its theory and application from that of the hard martial art styles.[4]In internal or soft technique martial arts, the receiver uses the aggressor's force and momentum against him by leading the attack in a direction where the receiver will be positioned at an advantage, then, in a seamless movement, effecting an appropriate martial arts technique. The goal of soft arts is to turn an adversary's force to his or her disadvantage, and use the least possible amount of force oneself.[5]

Tai chi training primarily involves learning solo routines, known as forms (套路 taolu). While the image of tai chi chuan in popular culture is typified by exceedingly slow movement, many tai chi styles (including the three most popular, Yang, Wu and Chen) have secondary forms of a faster pace. Some traditional schools of tai chi teach partner exercises known as pushing hands, and martial applications of the postures of the form.

Since the first widespread promotion of the health benefits of tai chi by Yang Shaohou (楊少侯), Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫), Wu Chien-ch'uan (吳鑑泉) and Sun Lutang (孫祿堂) in the early twentieth century,[6] it has developed a worldwide following among people with little or no interest in martial training.[7] Medical studies of tai chi support its effectiveness as an alternative exercise and a form of martial arts therapy. Focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form purportedly helps to combat stress by bringing about a state of mental calm and clarity. Regular practice of tai chi builds muscle strength, promotes balance and maintains flexibility. In some schools, aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are taught to advanced tai chi students [8].

Some martial arts, especially the Japanese martial arts, have students wear a uniform during practice. Tai chi chuan schools do not generally require a uniform, but both traditional and modern teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[9][10]

In the tai chi classics (a set of writings by traditional masters), the physical techniques of tai chi chuan are characterized by the use of leverage through the joints based on coordination in relaxation, rather than muscular tension, to neutralize or initiate attacks. The slow, repetitive work involved in learning to generate that leverage gently and measurably increases and opens the internal circulatory systems of the body (breath, body heat, blood, lymph, peristalsis, etc.).

The study of tai chi chuan involves three aspects:

- Physical fitness and health: Tai chi training relieves the physical effects of stress on the body and mind and promotes physical fitness. For those learning tai chi as a martial art, physical fitness is essential for effective self-defense.

- Meditation: The focus and calmness cultivated by the meditative aspect of tai chi is necessary for maintaining optimum health (relieving stress and maintaining homeostasis) and in application of the form as a soft style martial art.

- Martial art: The martial aspect of tai chi chuan is the study of appropriate change in response to outside forces; yielding and "sticking" to an incoming attack rather than attempting to meet it with opposing force. The ability to use tai chi as a form of self-defense in combat is the test of a student's understanding of the art.

History and styles

The formative period of tai chi is not historically documented and there are various contradictory theories regarding its origins. One legend relates that the Indian Monk, Bodhidharma, said to have introduced Chan Buddhism (similar to Japanese Zen Buddhism) at Shaolin Temple in Henan during the sixth century, taught physical exercises called “18 Hands of the Lohan,” which are said to be the origin of tai chi chuan and other methods of fighting without weapons, such as kung fu.

Other Chinese legends say that Zhang Sanfeng (Simplified Chinese: 张三丰; Traditional Chinese: 張三丰; pinyin: Zhāng Sānfēng; Wade-Giles: Chang1 San1-feng1, variant 張三豐, pronounced the same), a semi-mythical Chinese Daoist priest who is believed by some to have achieved immortality, created tai chi chuan in the monasteries of the Wudang Mountains of Hubei Province. Zhang Sanfeng is said variously to date from either the late Song Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty or Ming Dynasty. Legends from the seventeenth century onwards credit him with a Neo-Confucian syncretism of Chán Buddhist Shaolin martial arts with his mastery of Taoist Tao Yin (neigong) principles from which originated the concepts of soft, internal martial arts (neijia, 內家). Tai chi chuan's practical connection to and dependence upon the theories of Sung dynasty( 宋朝) Neo-Confucianism (a conscious synthesis of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian traditions, especially the teachings of Mencius 孟子) is claimed by some traditional schools.[4] Tai chi's theories and practice are believed by these schools to have been formulated by the Daoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the twelfth century, at about the same time that the principles of the Neo-Confucian school were making themselves felt in Chinese intellectual life.[4]

According to the legends, in his youth Zhang Sanfeng studied Tao Yin (導引, Pinyin dǎoyǐn) breathing exercises from his Taoist teachers[11] and martial arts at the Buddhist Shaolin monastery,[12] eventually combining the martial forms and breathing exercises to formulate the soft or internal principles we associate with tai chi chuan and related martial arts. Zhang Sanfeng is also sometimes attributed with the creation of the original 13 Movements of Tai Chi Chuan, found in all forms of tai chi chuan. Wu Tang monastery became known as an important martial center for many centuries thereafter, its many styles of internal kung fu(功夫) preserved and refined at various Daoist temples.

Documents preserved in the Yang and Wu family archives from the nineteenth century onwards credit Zhang Sanfeng with specifically creating tai chi chuan, and the tai chi chuan schools who ascribe the foundation of their art to Zhang traditionally celebrate his birthday as the 9th day of the 3rd Chinese lunar month.

Around the 1600s, the Chen clan of Chenjiagou (Chen Village), Henan province, China was identified as possessing a unique martial arts system. Oral history says that Chen Bu (the founder of Chen Village) brought this martial art from Shanxi when the clan was forced to leave there. According to historical sources, Chen Wangting (1600-1680), codified pre-existing Chen training practice into a corpus of seven routines including five routines of tai chi chuan (太极拳五路), 108-form Long Fist (一百零八势长拳)and Cannon Fist (炮捶一路). Wangting is said to have incorporated theories from earlier classic martial arts texts. A legend says that Jiang Fa (蔣發 Jiǎng Fā), a monk from Wudang mountain and a skilled martial artist, came to Chen village in the time of Chen Wangting or Chen Changxing (1771-1853) and transformed the Chen family art by teaching internal fighting practices.[13]

The other four modern orthodox family styles of tai chi chuan are traced to the teachings in the Chen family village in the early nineteenth century.[13][14]

There are five major styles of tai chi chuan, each named after the Chinese family from which it originated:

Chen style (陳氏)

The Chen family style (陳家、陳氏 or 陳式 太極拳) is the oldest and parent form of the five main tai chi chuan styles. It is third in world-wide popularity compared to the other main taijiquan styles. Chen style is characterized by its lower stances, more explicit “silk reeling” (chan si jin; continuous, cyclic patterns performed at constant speed with the "light touch" of drawing silk) and bursts of power (fajing).[15]

Many modern tai chi styles and teachers emphasize a particular aspect (health, aesthetics, meditation and/or competitive sport) in their practice of tai chi chuan, while the teaching methods of the five traditional family styles tend to retain the original orientation towards martial arts. Some argue that Chen style schools succeed to a greater degree in teaching tai chi chuan as a martial art.[15]

The Chen lao jia consists of two forms lao jia yi lu (old frame, 1st routine) and er lu (new frame, 2nd routine). Yi lu (the first empty hand form) at the beginner level is mostly done slowly with large motions interrupted by occasional expressions of fast power (fajing) that comprise less than 20 percent of the movements, with the overall purpose of teaching the body to move correctly. At the intermediate level it is practiced in very low stances (low frame) with an exploration of clear directional separation in power changes and in speed tempo. The movements become smaller and the changes in directional force become more subtle. At the advanced level the leg strength built at the previous level allows full relaxation and the potential for fajing in every movement. The second empty hand form, "er lu" or "cannon fist" is done faster and is used to add more advanced martial techniques such as advanced sweeping and more advanced fajing methods. Both forms also teach various martial techniques.

Around the time of the 14/15th generation after Chen Bu, Chen Village practice of tai chi chuan appears to have differentiated into two related but distinct practice traditions which are today known as big frame (ta chia, 大架, sometimes called large frame) and small frame. Big frame encompasses the classic "old frame" (lao jia) routines, yi lu and er lu, which are very well known today. It also includes the more recent "new frame" (xin chia) routines which evolved from the classic Old Way/Frame routines under Chen Fake in Beijing in his later years (1950s). Small frame tradition (xiao jia, 小架) is known mainly for its emphasis on internal movements; all "silk-reeling" action is within the body, and the limbs are the last place the motion occurs. This form emphasizes manipulation, seizing and grappling (qinna) rather than striking techniques. From the time of Chen Chang-hsing, the creator of these routines, it was taught privately in Chen Village.

In the late 1920s Chen Fake (陳發科, 陈发科, Chén Fākē, Ch'en Fa-k'e, 1887-1957) and his nephew broke with Chen family tradition and openly began to teach Chen style tai chi chuan, providing public classes in Beijing for many years. A powerful tradition of the Beijing Chen style, featuring Chen Fake’s "new frame" variant of the Chen Village "old frame" style, survived his death and spread throughout China. Following changes in Chinese foreign policy in the 1980s, Chinese Chen stylists migrated around the world, triggering a wave of interest and popularity in the West.

Weapon forms

Chen Tai Chi has several unique weapon forms.

- the 49 posture Straight Sword (Jian) form

- the 13 posture Broadsword (Dao) form

- Spear (Qiang) solo and partner forms

- 3, 8, and 13 posture Gun (staff) forms

- 30 posture Halberd (Da Dao/Kwan Dao) form

- several double weapons forms utilizing the above-mentioned items

Yang style (楊氏)

The founder of the Yang style, Yang Lu-ch'an (楊露禪), aka Yang Fu-k'ui (楊福魁, 1799-1872), began studying under Ch'en Chang-hsing in 1820. Yang's interpretation of tai chi chuan when he subsequently became a teacher in his own right was known as the Yang style, and led directly to the development of the other three major styles of tai chi chuan (see below). Yang Lu-ch'an and the art of tai chi chuan came to prominence when he was hired by the Chinese Imperial family to teach tai chi chuan to the elite Palace Battalion of the Imperial Guards in 1850, a position he held until his death.

Yang Lu-ch'an’s second son Yang Pan-hou (楊班侯, 1837-1890) was also retained as a martial arts instructor by the Chinese Imperial family and became the formal teacher of Wu Ch'uan-yü (Wu Quanyou), a Manchu Banner cavalry officer of the Palace Battalion. Wu Ch'uan-yü and his son, Wu Chien-ch'üan (Wu Jianquan), also a Banner officer, became known as the co-founders of the Wu style.

Yang Lu-ch'an also trained Wu Yu-hsiang (Wu Yuxiang, 武禹襄, 1813-1880) who also developed his own Wu style, which after three generations led to the development of Sun style tai chi chuan.

Yang Lu-ch'an’s third son Yang Chien-hou (Jianhou) (1839-1917) passed the tradition to his sons, Yang Shao-hou (楊少侯, 1862-1930) and Yang Ch'eng-fu (楊澄甫, 1883-1936). Yang Ch'eng-fu is largely responsible for standardizing and popularizing the Yang style tai chi chuan widely practiced today. Yang Ch'eng-fu removed the vigorous Fa-jing (發勁 release of power), energetic jumping, stamping, and other abrupt movements and emphasized Ta Chia (大架, large frame style), whose slow, steady, expansive and soft movements were suitable for general practitioners. Yang Ch'eng-fu moved to Shanghai in the 1920s, teaching there until the end of his life. His descendants are still teaching in schools associated with their family internationally.

Tung Ying-chieh (Dong Yingjie, 董英杰, 1898-1961), Ch'en Wei-ming (Chen Weiming), Fu Zhongwen (Fu Chung-wen, 1903-1994), Li Yaxuan (李雅轩, 1894-1976) and Cheng Man-ch'ing were famous students of Yang Ch'eng-fu. Each of them taught extensively, founding groups that teach tai chi to this day. Cheng Man-ch'ing, perhaps the most famous teacher outside of China, significantly shortened and simplified the traditional forms Yang taught him.

Wu or Wu/Hao style of Wu Yu-hsiang (Wu Yuxiang, 武氏)

The Wu or Wu (Hao) style (武氏 or 武/郝氏) of tai chi chuan established by Wu Yu-hsiang (武禹襄, 1813-1880), is separate from the more popular Wu style (吳氏) of Wu Chien-ch'üan. Wu Yu-hsiang, a scholar from a wealthy and influential family, became a senior student (along with his two older brothers Wu Ch'eng-ch'ing and Wu Ju-ch'ing) of Yang Lu-ch'an. A body of writing on the subject of t'ai chi theory attributed to Wu Yu-hsiang is considered influential by many other schools not directly associated with his style. Wu Yu-hsiang’s most famous student was his nephew, Li I-yü (李亦畬, 1832-1892), who taught Hao Wei-chen (郝為真, 1842-1920), who taught his son Hao Yüeh-ru (郝月如) who in turn taught his son Hao Shao-ju (Hao Shaoru, 郝少如) Wu Yu-hsiang's style of training, so that it is now sometimes known as Wu/Hao or just Hao style t'ai chi ch'uan. Hao Wei-chen also taught the famous Sun Lu-t'ang.

Hao Yüeh-ru taught during the 1920s when t'ai chi ch'uan was experiencing an initial degree of popularity, and is known for having simplified and standardized the forms he learned from his father in order to more effectively teach large numbers of beginners. Other famous tai chi chuan teachers, notably Yang Ch'eng-fu, Wu Chien-ch'üan and Wu Kung-i, made similar modifications to their beginning level forms around the same time.

Wu Yu-hsiang's tai chi chuan is a distinctive style with small, subtle movements; highly focused on balance, sensitivity and internal ch'i development. It is a rare style today, especially compared with the other major styles. Direct descendants of Li I-yü and Li Ch'i-hsüan still teach in China, but there are no longer Hao family members teaching the style.

Wu style of Wu Ch'uan-yü (Wu Quanyuo) and Wu Chien-ch'uan (Wu Jianquan, 吳氏)

Wu Ch'uan-yü (吳全佑, 1834–1902) was a military officer cadet of Manchu ancestry in the Yellow Banner camp (see Qing Dynasty Military) in the Forbidden City, Beijing and also a hereditary officer of the Imperial Guards Brigade.[16] He studied under Yang Lu-ch'an (楊露禪, 1799–1872), the martial arts instructor in the Imperial Guards, who was teaching t'ai chi ch'uan.[13]

The Wu style's distinctive hand form, pushing hands and weapons training emphasizes parallel footwork and the horse stance, with the feet relatively closer together than in the modern Yang or Chen styles. Small circle hand techniques are featured, although large circle techniques are trained as well. The Wu style's martial arts training focuses initially on grappling, throws (shuai chiao), tumbling, jumping, footsweeps, pressure point leverage and joint locks and breaks, in addition to more conventional t'ai chi sparring and fencing at advanced levels.[17]

Sun style Tai Chi Chuan (孫氏)

Sun style tai chi chuan is well known for its smooth, flowing movements which omit the more physically vigorous crouching, leaping and Fa jing of some other styles. The footwork of Sun style is unique; when one foot advances or retreats, the other follows. It also uses an open palm throughout the entirety of its main form, and exhibits small circular movements with the hand. Its gentle postures and high stances make it very suitable for geriatric exercise and martial arts therapy.

The Yang style is most popular in terms of number of practitioners, followed by Wu, Chen, Sun, and Wu/Hao.[4] The five major family styles share much underlying theory, but differ in their approaches to training. There are now dozens of new styles, hybrid styles and offshoots of the main styles, but the five family schools are recognized by the international community as being orthodox. Zhaobao Tai Chi (趙堡忽靈架太極拳), a close cousin of Chen style, has been newly recognized by Western practitioners as a distinct style.

Family trees

These family trees are not comprehensive. Names denoted by an asterisk are legendary or semi-legendary figures in the lineage; while their involvement in the lineage is accepted by most of the major schools, it is not independently verifiable from known historical records. The Cheng Man-ch'ing and Chinese Sports Commission short forms are derived from Yang family forms, but neither are recognized as Yang family tai chi chuan by standard-bearing Yang family teachers. The Chen, Yang and Wu families are now promoting their own shortened demonstration forms for competitive purposes.

Legendary figures

| Zhang Sanfeng c. 12th century NEIJIA | |||||||

| Wang Zongyue 1733-1795 | |||||||

Five major classical family styles

| Chen Wangting 1600–1680 9th generation Chen CHEN STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen Changxing 1771–1853 14th generation Chen Chen Old Frame | Chen Youben c. 1800s 14th generation Chen Chen New Frame | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Lu-ch'an 1799–1872 YANG STYLE | Chen Qingping 1795–1868 Chen Small Frame, Zhaobao Frame | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yang Pan-hou 1837–1892 Yang Small Frame | Yang Chien-hou 1839–1917 | Wu Yu-hsiang 1812–1880 WU/HAO STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ch'uan-yü 1834–1902 | Yang Shao-hou 1862–1930 Yang Small Frame | Yang Ch'eng-fu 1883–1936 Yang Big Frame | Li I-yü 1832–1892 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Chien-ch'üan 1870–1942 WU STYLE 108 Form | Yang Shou-chung 1910–85 | Hao Wei-chen 1849–1920 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Kung-i 1900–1970 | Sun Lu-t'ang 1861–1932 SUN STYLE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu Ta-k'uei 1923–1972 | Sun Hsing-i 1891–1929 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Modern forms

| Yang Ch`eng-fu | |||||||||||||||

| Cheng Man-ch'ing 1901–1975 Short (37) Form | Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing 24 Form | ||||||||||||||

| 1989 42 Competition Form (Wushu competition form combined from Sun, Wu, Chen, and Yang styles) | |||||||||||||||

Training and techniques

In literature preserved in its oldest schools, tai chi chuan is said to be a study of yin (receptive) and yang (active) principles, using terminology found in the Chinese classics, especially the Book of Changes (易經) and the Tao Te Ching( 道德經).[4]

The core training involves two primary features: the solo form (ch'üan or quán, 拳), a slow sequence of movements which emphasize a straight spine, abdominal breathing and a natural range of motion; and different styles of pushing hands (tui shou, 推手) that apply the movement principles of the solo form in a more practical way.

The solo form takes the students through a complete, natural range of motion over their center of gravity. Accurate, repeated practice of the solo routine improves posture, encourages circulation throughout the body, maintains flexibility of the joints and further familiarizes students with the martial application sequences implied by the forms. The major traditional styles of tai chi have forms which differ from each other cosmetically, but many obvious similarities point to their common origin. The solo forms, empty-hand and weapon sequences are catalogs of movements that are practiced individually in “pushing hands” and martial application scenarios to prepare students for self-defense training. In most traditional schools, different variations of the solo forms can be practiced, such as fast–slow, small circle–large circle, square–round (different expressions of leverage through the joints), low sitting/high sitting (the degree to which weight-bearing knees are kept bent throughout the form).

In the Dao De Jing (道德經), Lao Tzu( 老子) wrote,

"The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong." The philosophy of tai chi chuan is that if one uses “hardness” to resist violent force, both sides are certain to be injured to some degree. Such injury, according to tai chi theory, is a natural consequence of meeting brute force with brute force. Instead, students are taught not to directly fight or resist an incoming force, but to meet it in softness and follow its motion while remaining in physical contact until the incoming force of attack exhausts itself or can be safely redirected, meeting yang with yin. A primary goal of tai chi chuan training is to achieve this yin-yang or yang-yin balance in combat, and in a broader philosophical sense.

Tai chi's martial aspect relies on sensitivity to the opponent's movements and center of gravity to dictate appropriate responses. The primary goal of the martial tai chi student is to effectively affect or "capture" the opponent's center of gravity immediately upon contact.[18] The sensitivity needed to capture the opponent’s center of gravity is acquired over thousands of hours of yin (slow, repetitive, meditative, low impact) training followed by yang ("realistic," active, fast, high impact) martial training including forms, pushing hands and sparring. Tai chi trains in three basic ranges, close, medium and long. Pushes and open hand strikes are more common than punches, and kicks are usually to the legs and lower torso, never higher than the hip depending on style. The fingers, fists, palms, sides of the hands, wrists, forearms, elbows, shoulders, back, hips, knees and feet are commonly used to strike. Techniques such as strikes to the eyes, throat, heart, groin and other acupressure points are taught to advanced students. Joint traps, locks and breaks (chin na 擒拿) are also used. Most tai chi teachers expect their students to thoroughly learn defensive or neutralizing skills first, and a student will have to demonstrate proficiency with them before he or she can begin training in offensive skills. In the traditional schools, students are expected to show wu te (武德, martial virtue or heroism), to protect the defenseless and show mercy to opponents.[19]

In addition to the physical form, martial tai chi chuan schools also focus on how the energy of a strike affects the other person. Palm strikes that look the same physically may be performed in such a way that they have completely different effects on the target's body. A palm strike could simply push the person forward, be focused in such a way as to lift them vertically off the ground and break their center of gravity, or terminate the force of the strike within the other person's body with the intent of causing internal damage.

Other training exercises include:

- Weapons training and fencing applications employing the straight sword known as the jian or chien or gim (jiàn 劍); a heavier curved sabre, sometimes called a broadsword or tao (dāo 刀, which is actually considered a big knife); folding fan, also called san; 7-foot (2 m) wooden staff known as kun (棍); 7-foot (2 m) spear; and 13 foot (4 m) lance (both called qiāng 槍). More exotic weapons still used by some traditional styles are the large Dadao or Ta Tao (大刀) and Pudao or P'u Tao (撲刀) sabres, halberd (jǐ 戟), cane, rope-dart, three sectional staff, wind and fire wheels, lasso, whip, chain whip and steel whip.

- Two-person tournament sparring, as part of push hands competitions and/or sanshou (散手);

- Breathing exercises; nei kung (內功 nèigōng) or, more commonly, ch'i kung (氣功 qìgōng) to develop ch'i (氣 qì) or "breath energy" in coordination with physical movement and post standing or combinations of the two. These were formerly taught only to disciples as a separate, complementary training system. In the last 50 years they have become better known to the general public.

Modern tai chi

Tai chi classes have become popular in hospitals, clinics, community and senior centers in the last 20 years or so, as baby boomers aged and tai chi chuan acquired a reputation as an ideal low-stress training for seniors.[20][21] As a result of this popularity, there has been some divergence between those who practice tai chi primarily for self-defense, those who practice it for its aesthetic appeal (see wushu, 武術, below), and those who are more interested in its benefits to physical and mental health. The wushu aspect is primarily for show; the forms taught for those purposes are designed to earn points in competition rather than to maintain physical health or strengthen martial ability. More traditional stylists believe the two aspects of health and martial arts are equally necessary: the yin and yang of tai chi chuan. The tai chi "family" schools therefore still present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students in studying the art.[22]

Along with Yoga, tai chi is one of the fastest growing fitness and health maintenance activities in the United States.[21]

Tai chi as sport

To standardize tai chi chuan for wushu tournament judging, and because many of the family tai chi chuan teachers had either moved out of China or had been forced to stop teaching after the Communist regime was established in 1949, the Chinese government established the Chinese Sports Committee, which brought together four wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures in 1956. They wanted to retain the look of tai chi chuan, but create a routine that was less difficult to teach and much less difficult to learn than longer (generally 88 to 108 posture), classical, solo hand forms. In 1976, for demonstration purposes, a slightly longer form, the Combined 48 Forms, was developed that still did not require the memory, balance and coordination of the traditional forms. Features of the classical forms from four of the original styles, Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun, were simplified and combined. As tai chi again became popular on the mainland, more competitive forms were developed to be completed within a six-minute time limit.

In the late-1980s, the Chinese Sports Committee standardized many different competition forms. Different teams created five sets of forms to represent the four major styles as well as combined forms. Each set of forms was named after its style; for example, the Chen Style National Competition Form is the 56 Forms, and the combined forms are The 42 Form or simply the Competition Form. Another modern form is the 67 movements Combined Tai-Chi Chuan form, created in the 1950s, blending characteristics of the Yang, Wu, Sun, Chen and Fu styles.

These modern versions of tai chi chuan (pinyin: Tai ji quan) have since become an integral part of international wushu tournament competition, and have been featured in several popular Chinese movies starring or choreographed by well known wushu competitors, such as Jet Li ( 李連傑) and Donnie Yen ( 甄子丹).

At the 11th Asian Games in 1990, wushu was included for the first time and the 42 Forms was chosen to represent tai chi. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) has applied for wushu to be part of the Olympic games, but will not count medals.[23]

Health benefits

Before its introduction to Western students, the health benefits of tai chi chuan were largely understood in terms of traditional Chinese medicine, which is based on a view of the body and healing mechanisms not always studied or supported by modern science. Some prominent tai chi teachers have advocated subjecting tai chi to rigorous scientific studies to gain acceptance in the West.[24] Researchers have found that long-term tai chi practice shows some favorable but statistically insignificant effects on the promotion of balance control, flexibility and cardiovascular fitness and reduced the risk of falls in elderly patients.[25] The studies also show some reduced pain, stress and anxiety in healthy subjects. Other studies have indicated improved cardiovascular and respiratory function in healthy subjects as well as those who had undergone coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients that suffer from heart failure, high blood pressure, heart attacks, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's may also benefit from tai chi. Tai chi, along with yoga, has reduced levels of LDLs 20–26 milligrams when practiced for 12–14 weeks.[26] However, a thorough review of most of these studies showed limitations or biases that made it difficult to draw firm conclusions on the benefits of tai chi.[24] There have also been indications that tai chi might have some effect on noradrenaline and cortisol production and consequently on mood and heart rate. However, as with many of these studies, the effect may be no different than those derived from other types of physical exercise.[27]

In one study, tai chi has also been shown to reduce the symptoms of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in 13 adolescents. The improvement in symptoms seem to persist after the tai chi sessions were terminated.[28] Tai chi's gentle, low impact movements burn more calories than surfing and nearly as many as downhill skiing.[29] In addition, a pilot study, which has not been published in a peer-reviewed medical journal, has found preliminary evidence that tai chi and related qigong( 氣功) may reduce the severity of diabetes.[30]

Some health professionals have called for more in-depth studies to determine the most beneficial style, optimal duration of practice, and relative effectiveness of tai chi compared to other forms of exercise.[24]

Tai chi chuan in fiction

Neijia ( 內家) and specifically Tai chi are featured in many wuxia (武俠, a Chinese martial literary form) novels, films, and television series, among which are Yuen Wo Ping's Tai Chi Master starring Jet Li, and the popular Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Ang Lee (李安)'s first western film Pushing Hands, features a traditional tai chi chuan teacher as the lead character. Internal concepts may even be the subject of parody, such as in Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle. Fictional portrayals often refer to Zhang Sanfeng and the Taoist monasteries on Wudangshan.

See also

- Chinese martial arts

Notes

- ↑ Douglas Wile. Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). (State University of New York Press. 1995).

- ↑ Douglas Wile. Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. (Sweet Ch'i Press. 1983. ISBN 978-0912059013).

- ↑ Man-ch'ing Cheng. Cheng-Tzu's Thirteen Treatises on T'ai Chi Ch'uan. (North Atlantic Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0938190455), 21

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Douglas Wile, "Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion." Journal of Asian Martial Arts 16(4) (2007) Via Media Publishing issn 1057-8358 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Wile2007" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Zhongwen Fu and Louis Swaine, (translator). Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. (Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake Books, (1996) 2006. ISBN 1583941525)

- ↑ Wile, 1995

- ↑ T'ai Chi gently reduces blood pressure in elderly. The Lancet Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ Kung-tsao Wu. Wu Family T'ai Chi Ch'uan (吳家太極拳). (Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association. 2006.)

- ↑ Dr. Paul Lam, What should I wear to practice Tai Chi? Tai Chi Productions Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ Fu and Swaine

- ↑ Cen Lao, "The Evolution of T'ai Chi Ch'uan." T’AI CHI The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan 21 (2) (April 1997) Wayfarer Publications issn 0730-1049

- ↑ Wolfram Eberhard. A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Wile, 1995 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Wile1995" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Wile, 1983.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ren Guang Yi, Stephen Berkwick, Jose Figueroa. Taijiquan: Chen 38 form and applications. (North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0804835268)

- ↑ Kung-tsao Wu. Wu Family T'ai Chi Ch'uan (吳家太極拳). (Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association, (1980), 2006. ISBN 097804990X)

- ↑ Margaret Philip-Simpson, "A Look at Wu Style Teaching Methods" - T’AI CHI The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch'uan 19 (3) (June 1995), Wayfarer Publications

- ↑ Wu, 2006

- ↑ Wile, 1995

- ↑ Y. L. Yip, "Pivot – Qi." The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness 12 (3)(Autumn 2002) Insight Graphics Publishers issn 1056-4004

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 SGMA 2007 Sports & Fitness Participation Report From the USA Sports Participation Study, 2. SGMA. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ Doug Woolidge, "T’AI CHI" The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan. 21 (3) (June 1997) Wayfarer Publications, issn 0730-1049

- ↑ Wushu likely to be a "specially-set" sport at Olympics Chinese Olympic Committee, 2006.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 JP Collet & Lau J Wang. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review, Archives of Internal Medicine 2004, 164 (5): 493–501. Retrieved November 11, 2008

- ↑ SL Wolf, RW Sattin & M Kutner. "Intense tai chi exercise training and fall occurrences in older, transitionally frail adults: a randomized, controlled trial." Journal of the American Geriatric Society 2003, 51 (12): 1693–701. doi=10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51552.x Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ Jane E. Brody, Cutting Cholesterol, an Uphill Battle, The New York Times (August 21, 2007) Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ P. Jin, Changes in Heart Rate, Noradrenaline, Cortisol and Mood During Tai Chi Journal of Psychosomatic Research 33 (2): 197–206. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- ↑ M. Hernandez-Reif, TM Field, & E. Thimas, 2001. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: benefits from Tai Chi. [1]. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies 5 (2):120–123. accessdate 2007-04-13 doi=10.1054/jbmt.2000.0219

- ↑ Calories burned during exercise CHART.[2]. NutriStrategy. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ LD Pennington, 2006 Tai chi: an effective alternative exercise. DiabetesHealth Retrieved November 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cheng Man-ch'ing. Cheng-Tzu's Thirteen Treatises on T'ai Chi Ch'uan. North Atlantic Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0938190455.

- Eberhard, Wolfram. A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986. ISBN 0415002281.

- Fu, Zhongwen; translator, Louis Swaine. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Berkeley, CA: Blue Snake Books. 2006. ISBN 1583941525.

- Lao, Cen. "The Evolution of T'ai Chi Ch'uan." T’AI CHI The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan 21 (2)(April 1997).

- Philip-Simpson, Margaret, "A Look at Wu Style Teaching Methods." T’AI CHI The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch'uan 19 (3)(June 1995), Wayfarer Publications

- Ren, Guang Yi, and Stephen Berkwick, Jose Figueroa. Taijiquan: Chen 38 form and applications. North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0804835268.

- Wile, Douglas. Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty. (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. 1995. ISBN 978-0791426548.

- Wile, Douglas. "Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion." Journal of Asian Martial Arts 16 (4)(2007).

- Wile, Douglas. Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch'i Press. 1983. ISBN 978-0912059013.

- Woolidge, Doug. T’AI CHI. The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan 21 (3)(June 1997).

- Wu, Kung-tsao. Wu Family T'ai Chi Ch'uan (吳家太極拳). Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association. 2006. ISBN 097804990X.

- Yip, Y. L. "Pivot – Qi." The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness 12 (3)(Autumn 2002).

External Sources

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Medical Research on T'ai Chi & Qigong (Chi Kung) World Tai Chi Day.

- World T'ai Chi & Qigong Day's Headline News. World Tai Chi Day.

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- "Tai Chi Exercises: Fad Unsettles Indonesia"

- Tai Chi 'improves body and mind' at BBC

- Yang Zhenduo's Yang style at YouTube

- Wu Yinghua's Wu Jianquan style

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Neijia history

- Wuxia history

- Hard_and_soft_(martial_arts history

- Chen_style_tai_chi_chuan history

- Wu_(Hao)_style_tai_chi_chuan history

- Wu_style_tai_chi_chuan history

- Sun_style_tai_chi_chuan history

- Zhang_Sanfeng&oldid=243083106 Zhang_Sanfeng Zhang_Sanfeng&action=history history

- Silk_reeling history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.