Tang Dynasty

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tang Dynasty (June 18, 618 – June 4, 907 C.E.) was preceded by the Sui Dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period in China. The dynasty was founded by the Li family, who seized opportunity in the decline and collapse of the Sui Empire. The dynasty was interrupted briefly by the Second Zhou Dynasty (October 16, 690 – March 3, 705) when Empress Wu Zetian seized the throne (the first and only Chinese Empress to rule in her own right).

The Tang Dynasty, with its capital at Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), the most populous city in the world at the time, is regarded by historians as a high point in Chinese civilization—equal to or surpassing that of the Han Dynasty—as well as a golden age of cosmopolitan culture. Its territory, acquired through the military campaigns of its early rulers, was greater than that of the Han period and rivaled that of the later Yuan Dynasty and Qing Dynasty. The dynasty featured two of Chinese history's major prosperity periods, the Zhen'guan Prosperity (Tang Taizong) and Kaiyuan Prosperity (Tang Xuanzong's early rule). The enormous Grand Canal of China (still the longest canal in the world) built during the previous Sui Dynasty facilitated the rise of new urban settlements along its route, as well as increased accessibility in mainland China to its own indigenous commercial market.

In Chinese history, the Tang Dynasty was largely a period of progress and stability (except for the An Lushan Rebellion and decline of central power during the ninth century). The Tang era is considered the greatest age for Chinese poetry. Two of China's most famous historical poets, Du Fu and Li Bai, belonged to this age, as well as Meng Haoran and Bai Juyi. There were also many famous visual artists, such as the renowned painters Han Gan, Wu Daozi, and Zhan Ziqian, although classic Chinese painting would not reach its zenith until the Song and Ming dynasties. By the ninth century the dynasty and central government where in decline. But, their art and culture would continue to flourish. Although the weakened central government withdrew largely from managing the economy, commercialism and mercantile affairs continued to thrive regardless. At its height, the Tang Dynasty had a population of 50 million people.

| History of China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | |||||||

| 3 Sovereigns and 5 Emperors | |||||||

| Xia Dynasty 2070–1600 B.C.E. | |||||||

| Shang Dynasty 1600–1046 B.C.E. | |||||||

| Zhou Dynasty 1122–256 B.C.E. | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn Period | |||||||

| Warring States Period | |||||||

| IMPERIAL | |||||||

| Qin Dynasty 221 B.C.E.–206 B.C.E. | |||||||

| Han Dynasty 206 B.C.E.–220 C.E. | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin Dynasty | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 C.E. | |||||||

| Wu, Shu & Wei | |||||||

| Jin Dynasty 265–420 C.E. | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | 16 Kingdoms 304–439 C.E. | ||||||

| Southern & Northern Dynasties 420–589 C.E. | |||||||

| Sui Dynasty 581–619 C.E. | |||||||

| Tang Dynasty 618–907 C.E. | |||||||

| 5 Dynasties & 10 Kingdoms 907–960 C.E. |

Liao Dynasty 907–1125 C.E. | ||||||

| Song Dynasty 960–1279 C.E. |

|||||||

| Northern Song | W. Xia Dyn. | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin Dyn. | ||||||

| Yuan Dynasty 1271–1368 C.E. | |||||||

| Ming Dynasty 1368–1644 C.E. | |||||||

| Qing Dynasty 1644–1911 C.E. | |||||||

| MODERN | |||||||

| Republic of China 1911–present | |||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present |

Republic of China | ||||||

Timeline of Chinese history Dynasties in Chinese history Military history of China History of Chinese art History of science and technology in China History of Education in China | |||||||

Establishment

Li Yuan (later to become Emperor Gaozu) was a former governor of Taiyuan when other government officials were fighting off bandit leaders in the collapse of the Sui Empire. With prestige and military record 'under his belt', he later rose in rebellion at the urging of his second son, the skilled and militant Li Shimin (later Emperor Taizong of Tang). Their family came from the background of the northwest military aristocracy. In fact, the mothers of both Emperor Yang of Sui and Gaozu of Tang were sisters, making these two emperors of different dynasties first cousins.[1]

Li Yuan installed a puppet child emperor of the Sui dynasty in 617 but he eventually removed the child emperor and established the Tang dynasty in 618. Li Yuan ruled until 626 before being forcefully deposed by his son, Li Shimin, known as "Tang Taizong." Li Shimin had commanded troops since the age of eighteen, had prowess with a bow, sword, lance and in cavalry charges. In a violent elimination of fellow royal family for political power, Li Shimin ambushed two of his brothers, one being the heir to the throne, and had all ten of their sons executed. Shortly after, his father abdicated in favor of him and he ascended the throne as Emperor Taizong of Tang. Although his rise to power was brutal and violent, he was also known for his benevolence and care for governance. For example, in 628 C.E., Emperor Taizong held a Buddhist memorial service for the casualties of war and in 629 had Buddhist monasteries erected at the sites of major battles so that monks could pray for the fallen on both sides of the fight.[2]

Taizong then set out to solve internal problems within the government, problems which had constantly plagued past dynasties. He issued a new legal code that subsequent Chinese dynasties would model theirs upon, as well as neighboring polities in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. The Emperor had three administrations (省, shěng), which were obliged to draft, review, and implement policies respectively. There were also six divisions (部, bù) under the administration that implemented policy, each of which was assigned different tasks.

Although the founders of the Tang related to the glory of the earlier Han Dynasty, the basis for much of their administrative organization was very similar to the previous Southern and Northern Dynasties.[1] The Northern Zhou divisional militia (fubing) was continued by the Tang governments, along with farmer-soldiers serving in rotation from the capital or frontier in order to receive appropriated farmland. The equal-field system of the Northern Wei Dynasty was also kept, with a few modifications.[1]

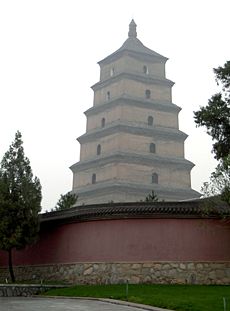

The center of the political power of the Tang was the capital city of Chang'an (modern Xi'an), where the emperor maintained his large palace and entertained political emissaries with music, acrobatic stunts, poetry, paintings, early dramatic theater performances (see Pear Garden acting troupe.

Culture and Society

Both the Sui and Tang Dynasties had turned away from the more militant culture of the preceding Northern Dynasties, in favor of staunch civil Confucianism. A government system supported by a large class of Confucian literati selected through civil service examinations was perfected under Tang rule. This competitive procedure was designed to draw the best talents into government. But perhaps an even greater consideration for the Tang rulers, was to create a body of career officials having no autonomous territorial or functional power base. As it turned out, these scholar-officials acquired status in their local communities, family ties, and shared values that connected them to the imperial court. From Tang times until the closing days of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, scholar officials functioned often as intermediaries between the grassroots level and the government.

The Tang period was the golden age of Chinese literature and art (see Tang Dynasty art). Tang poems in particular are still read today. For example, Du Fu's poem To My Retired Friend Wei:

- It is almost as hard for friends to meet

- as for the morning and evening stars.

- Tonight then is a rare event,

- joining, in the candlelight,

- two men who were young not long ago

- but now are turning grey at the temples.

- … To find that half our friends are dead

- shocks us, burns our hearts with grief.

- We little guessed it would be twenty years

- Before I could visit you again.

- When I went away, you were still unmarried;

- But now these boys and girls in a row

- are very kind to their father's old friend.

- They ask me where I have been on my journey;

- and then, when we have talked awhile,

- they bring and show me wines and dishes,

- spring chives cut in the night-rain

- and brown rice cooked freshly a special way.

- … My host proclaims it a festival,

- He urges me to drink ten cups—

- but what ten cups could make me as drunk

- as I always am with your love in my heart?

- … Tomorrow the mountains will separate us;

- after tomorrow - who can say? —Du Fu [3]

Stimulated by contact with India and the Middle East, the Empire saw a flowering of creativity in many fields. Buddhism, originating in India around the time of Confucius, continued to flourish during the Tang period and was adopted by the imperial family, becoming thoroughly sinicized and a permanent part of Chinese traditional culture. In an age before Neo-Confucianism and figures such as Zhu Xi, Buddhism had begun to flourish in China during the Southern and Northern Dynasties and became the dominant ideology during the prosperous Tang. However, situations changed as the dynasty and central government began to decline from civil authority into rule of regional military governors (jiedushi). During the 9th century, as economic prosperity was in decline, Buddhist convents and temples that had been exempt from state taxes were now targeted for taxation and their land for liquidation in order to increase the states failing revenues. Buddhism became heavily persecuted in late Tang China. Although, it would remain within the framework of Chinese cultural it never again gained its dominant status. This situation also came about through new revival of interest in native Chinese philosophies, such as Confucianism and Daoism. The "brilliant polemicist and ardent xenophobe" known as Han Yu (786 - 824) was one of the first men of the Tang to denounce Buddhism.[4] Although his contemporaries found him crude and obnoxious, he would foreshadow the later persecution of Buddhism in the Tang, as well as the revival of Confucian theory with the rise of Neo-Confucianism of the Song Dynasty.[4]

Woodblock printing

Block printing made the written word available to vastly greater audiences. The text of the Diamond Sutra is an early example of Chinese woodblock printing, complete with illustrations embedded with the text. With so many more books coming into circulation for the general public, literacy rates could improve, along with the lower classes being able to obtain cheaper sources of study. Therefore, there were more lower class people seen entering the Imperial Examinations and passing them by the later Song Dynasty (960-1279). Although the later Bi Sheng's movable type printing in the eleventh century was innovative for his period, woodblock printing that became widespread in the Tang would remain the dominant printing type in China until the more advanced printing press from Europe became widely accepted and used in East Asia.

Technology during the Tang period was built also upon the precedents of the past. The mechanical gear systems of Zhang Heng and Ma Jun gave the Tang engineer, astronomer and Buddhist monk Yi Xing (683-727) a great source of influence when he invented the world's first escapement mechanism in 725 C.E.[5] This was used alongside a clepsydra clock and waterwheel to power a rotating armillary sphere in representation of astronomical observation.[6]

Women's social rights and social status during the Tang era were also incredibly liberal-minded for the medieval period. Women who were full-figured (even plump) were considered attractive by men, as men also enjoyed the presence of assertive, active women. For example, the foreign horse-riding sport of polo (from Persia) became a wildly popular trend amongst the Chinese elite, as women often played the sport. There are even glazed earthenware figurines from the time period showing women playing the sport.

During the earlier Southern and Northern Dynasties (and perhaps even earlier) the drink of tea had been popular in southern China. Tea comes from the leaf buds of Camelia sinensis, native to southwestern China. Tea was viewed then as a beverage of tasteful pleasure and looked upon with pharmacological purpose as well. During the Tang Dynasty, tea was synonymous with everything sophisticated in society. The eighth century author Lu Yu (known as the Sage of Tea) even wrote a treatise on the art of drinking tea, called the Classic of Tea (Chájīng).[7] Although wrapping paper had been used in China since the 2nd century B.C.E.,[8] during the Tang Dynasty the Chinese were using wrapping paper as folded and sewn square bags to hold and preserve the flavor of tea leaves.[8] Indeed, paper found many other uses besides writing and wrapping during the Tang. Earlier, the first recorded use of toilet paper was made in 589 by the scholar official Yan Zhitui,[9] and in 851 (during the Tang) an Arab traveler commented on how the Chinese were not careful about cleanliness because they did not wash with water when going to the bathroom; instead, he said, they simply used paper to wipe with.[9]

Chang'an, the Tang Capital

Although Chang'an was the site for the capital of the earlier Han and Jin dynasties, after subsequent destruction in warfare, it was the Sui Dynasty model that comprised the Tang era capital. The roughly-square dimensions of the city had six miles of outer walls running east to west and more than five miles of outer walls running north to south. From the large Mingde Gates located mid-center of the main southern wall, a wide city avenue stretched from there all the way north to the central administrative city, behind which was the Chentian Gate of the royal palace, or Imperial City. Intersecting this were fourteen main streets running east to west, while eleven main streets ran north to south. These main intersecting roads formed 108 rectangular wards with walls and four gates each. The city was made famous for this checkerboard pattern of main roads with walled and gated districts, its layout even mentioned in one of Du Fu's poems. Of these 108 wards, two of them were designated as government-supervised markets, and other space reserved for temples, gardens, etc.[2]

The Tang capital was the largest city in the world at its time, the population of the city wards and its outlying suburbs reaching 2 million inhabitants.[2] The Tang capital was very cosmopolitan, with ethnicities of Persia, Central Asia, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, India and many other places living within. Naturally, with this plethora of different ethnicities living in Chang'an, there were also many different practiced religions, such as Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Islam. During the Heian period, the city of Kyoto in Japan (like many cities) was arranged in the checkerboard street grid pattern of the Tang capital and in accordance with traditional geomancy following the model of Chang'an/Xi'an.[2]

Administration and Politics

Following the example from the Sui, the Tang abandoned the Nine Ranks System in favor of a large civil service system. The Tang drafted learned and skilled students of Confucian studies who had passed standardized exams, and appointed them as state bureaucrats in the local, provincial, and central government (see Imperial Examination). These difficult exams were largely based on the Confucian classics, yet during the Tang Dynasty other subjects of study were made requirements for officials, even the recitation of poetry. The latter fell under the part of the exam known as the jinshi ('presented scholar examination'), which also included requirements for writing essay-style responses to questions on general and specific matters of governance and politics.[10]

These exams differed from the exams given by previous dynasties, in that they were open to all (male) citizens of all classes, not just those wealthy enough to receive a recommendation. Religion, namely Buddhism, also played a role in Tang politics. People bidding for office would have monks from Buddhist temples pray for them in public in return for cash donations or gifts if the person was to be elected.

Taxes and the Census

The Tang government attempted to create an accurate census of their empire's population size, mostly for effective taxation and matters of military conscription for each region. The early Tang government established the grain tax and cloth tax at a relatively low rate for each household. This was meant to encourage households to enroll for taxation and not avoid authorities, thus providing the government with the most accurate estimate possible. In the census of 609 C.E., the population was tallied by efforts of the government at a size of 9 million households, or about 50 million people.[1] Even if a rather significant amount of people had avoided the registration process of the tax census, the population size during the Tang had not grown since the earlier Han Dynasty (the census of the year 2 C.E. being 59 million people).[1] Chinese population size would not dramatically increase until the Song Dynasty (960-1279 C.E.), where the population doubled to 100 million people due to extensive rice cultivation in central and southern China.

Military and foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy, the Chinese had to deal now with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui and Tang government repaired fortifications, received their trade and tribute missions, sent royal princesses off to marry Turkic clan leaders, stirred trouble and conflict amongst ethnic groups against the Turks and recruited non-Chinese into the military. In the year 630 C.E., the Tang government issued order for an ultimately successful military campaign in capturing areas of modern-day northern Shaanxi province and southern Mongolia from the Turks. After this military victory, Emperor Taizong won the title of Great Khan amongst the various Turks in the region who pledged their allegiance to him and the Chinese empire. While the Turks were settled in the Ordos region (former territory of the Xiongnu), the Tang government took on the military policy of dominating the central steppe. Like the earlier Han Dynasty, the Tang Dynasty (along with Turkic allies) conquered and subdued Central Asia during the 640s and 650s C.E.[10]

Like the emperors of the Sui Dynasty before him, Taizong established a military campaign in 644 against the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo. Since Han Dynasty China once had a commandery in ancient northern Korea, the Tang Chinese desired to incorporate the region into their own empire. Allying with the Korean Silla Kingdom, the Chinese fought against Baekje and their Yamato Japanese allies in the Battle of Baekgang in August of 663 C.E., a decisive Tang-Silla victory. The Tang Dynasty navy had several different ship types at its disposal to engage in naval warfare, these ships described by Li Quan in his Taipai Yinjing (Canon of the White and Gloomy Planet of War) of 759 C.E.[11] There was also made a joint invasion with Silla against Goguryeo. Goguryeo defeated a Tang Army lead by King Taijong in 644, where King Taijong was wounded in the Battle of Ansi Fortress in Yodong. Some historians assert that he was wounded by the Goguryeo general Yang Manchun. Because of his wounds, he died soon after the war was lost. By 668 C.E., the Kingdom of Goguryeo was no more. However, the Goguryeo Kingdom remained in the hands of Unified Silla, not Tang.

Some of the major kingdoms paying tribute to the Tang Dynasty included Kashmir, Neparo (Nepal), Vietnam, Japan, Korea, over nine kingdoms located in Amu Darya and Syr Darya valley in south of mid-Asia. Nomadic kingdoms addressed the Emperor of Tang China respectfully as Tian Kehan (Celestial Kaghan) (天可汗). The seventh to eighth century was generally considered the zenith point of the Tang dynasty. Emperor Tang Xuanzong brought the Middle Kingdom to its "Golden Age" while the Silk Road thrived, with sway over Indochina in the south, and in the West China was the protector of Kashmir and master of the Pamirs.

Trade and the spread of culture

Through use of the land trade along the Silk Road and maritime trade by sail at sea, the Tang were able to gain many new technologies, cultural practices, rare luxury and contemporary items. From the Middle East the Tang were able to acquire a new taste in fashion, favoring trousers over robes, new improvements on ceramics, and rare ingenious paintings. To the Middle East, the Islamic world coveted and purchased in bulk Chinese goods such as lacquer-wares and porcelain wares.

The Silk Road

Under this period of the Pax Sinica, the Silk Road, the most important pre-modern trade route, reached its golden age, whereby Persian and Sogdian merchants benefited from the commerce between East and West. At the same time, the Chinese empire welcomed foreign cultures, making the Tang capital the most cosmopolitan area in the world. In addition, the maritime port city of Guangzhou in the south was also a home to many foreign merchants and travelers from abroad.

Although the Silk Road from China to the West was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141 B.C.E. - 87 B.C.E.) centuries before, it was reopened by the Tang in Zhengguan Year 13 (639 C.E.) when Huo Jun Ji conquered the West, and remained open for about 60 years. It was closed after the majority of vassals rebelled, blocking the road. About 20 years later, during Xuanzong's period, the Silk Road reopened when the Tang empire took over the Western Turk lands, once again reconnecting West and East for trade. After the An Shi Rebellion, the Tang Empire lost control over many of its outer western lands, which largely cut off China's direct access to the Silk Road. However, the Chinese still had maritime affairs.

Maritime trade abroad

Although the 5th century Buddhist monk Fa Xian sailed through the Indian Ocean and traveled to places of modern-day Sri Lanka and India, it was during the Tang Dynasty that Chinese maritime influence was extended to the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up even the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia) and Somalia in East Africa.[12] From the same Quraysh tribe of Muhammad, Sa'd ibn Abi-Waqqas sailed from Ethiopia to China during the reign of Emperor Gaozu. In the 630s C.E., he traveled back to China with a copy of the Qur'an, establishing China's first mosque, the Mosque of Remembrance. To this day he is still buried in a Muslim cemetery at Guangzhou.

During the Tang Dynasty, thousands of foreigners came and lived in Guangzhou for trade and commercial ties with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Jews and Nestorian Christians of the Near East and many others (much like Chang'an). In 748 C.E., the Buddhist monk Jian Zhen described Guangzhou as a bustling mercantile center where many large and impressive foreign ships came to dock. He wrote that "many big ships came from Borneo, Persia, Qunglun (Indonesia/Java)… with … spices, pearls, and jade piled up mountain high",[13] as written in the Yue Jue Shu (Lost Records of the State of Yue). After the Arabs burned and looted Guangzhou in 758 C.E., the Tang government reacted by shutting the port down for roughly five decades. However, when the port reopened it continued to thrive. In 851 C.E. the Arab merchant Suleiman al-Tajir observed the manufacturing of Chinese porcelain and admired its transparent quality.[14] He also provided description on the mosque at Guangzhou, its granaries, its local government administration, some of its written records, the treatment of travellers, along with the use of ceramics, rice-wine and tea.[15] However, in another bloody episode at Guangzhou in 878 C.E., the Chinese rebel Huang Chao ransacked the city, and purportedly slaughtered thousands of native Chinese, along with foreign Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the process. His rebellion was eventually suppressed in 884.

Beginning in 785 C.E., the Chinese began to call regularly at Sufala on the East African coast in order to cut out Arab middle-men,[16] with various contemporary Chinese sources giving detailed descriptions of trade in Africa. In 863 the Chinese author Duan Chengshi provided detailed description about the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade in a country called Bobali, which historians point to the possibility of being Berbera in Somalia.[17] In Fustat (old Cairo), Egypt, the fame of Chinese ceramics there led to an enormous demand for Chinese goods, hence Chinese often traveled there, also in later periods such as Fatimid Egypt. From this time period, the Arab merchant Shulama once wrote of his admiration for Chinese seafaring junks, but noted that the draft was too deep for them to enter the Euphrates River, which forced them to land small boats for passengers and cargo.[18] Shulama also noted in his writing that Chinese ships were often very large, large enough to carry aboard 600 to 700 passengers each.

Chinese geographers such as Jia Dan wrote accurate descriptions of places far abroad. In his work written between 785 and 805 C.E., he described the sea route going into the mouth of the Persian Gulf and that the medieval Iranians (whom he called the people of the Luo-He-Yi country) had erected 'ornamental pillars' in the sea that acted as lighthouse beacons for ships that might go astray.[19] Confirming Jia's reports about lighthouses in the Persian Gulf, Arabic writers a century after Jia wrote of the same structures, writers such as al-Mas'udi and al-Muqaddasi. The Chinese also used pagoda towers as lighthouses, such as the Song Dynasty era Liuhe Pagoda of 1165, in Hangzhou. The Tang Dynasty Chinese diplomat Wang Xuan-ce traveled to Magadha (modern northeastern India) during the seventh century C.E. Afterwards he wrote the book Zhang Tian-zhu Guo Tu (Illustrated Accounts of Central India), which included a wealth of geographical information.[20]

Decline

It is yet unkown the actual series of events that lead to the decline of the Tang Dynasty.

By the 740s C.E., the Arabs of Khurasan - by then under Abbasid control - had established a presence in the Ferghana basin and in Sogdiana. At the Battle of Talas in 751 C.E., mercenaries under the Chinese defected, which forced Tang commander Gao Xianzhi to retreat.

Soon afterward, the An Shi Rebellion 756 - 761 C.E. destroyed the prosperity that took years to be established. It left the dynasty weakened, the Tang never regained its glory days of the seventh and eighth century. The Tang were eventually driven out of Central Asia and imperial China did not regain ground in that region until the Mongol led regime during the Yuan Dynasty.

Another legacy of the An Shi rebellion were the gradual rise of regional military governors (jiedushi) which slowly came to challenge the power of the central government. The Tang government relied on these governors and their armies for protection and to suppress locals that would take up arms against the government. In return, the central government would acknowledge the rights of these governors to maintain their army, collect taxes and even to pass on their title. With the central government collapsing in authority over the various regions of the empire, it was recorded in 845 C.E. that bandits and river pirates in parties of 100 or more were largely unchecked by authorities while they plundered settlements along the Yangtze River.[21]Bowman, 105</ref>

In 858 C.E., flooding along the Grand Canal inundated vast tracts of land and terrain of the North China Plain, which drowned tens of thousands of people. [21] The Chinese belief in the Mandate of Heaven granted to the ailing Tang was also challenged when natural calamities occurred, forcing many to believe the Heavens were displeased and that the Tang had lost their right to rule. Then in 873 C.E. a disastrous harvest shook the foundations of the empire and tens of thousands faced famine and starvation.[21] In the earlier period of the Tang, the central government was able to meet crisis in the harvest, as it was recorded from 714-719 C.E. that the Tang government took assertive action in responding to natural disasters by extending the price regulation granary system throughout the country.[21] The central government was then able to build a large surplus stock of foods to meet the danger of rising famine,[21], yet the Tang government in the ninth century was nearly helpless in dealing with any calamity.

Fall of the Tang dynasty

Near the end of the Tang Dynasty, regional military governors took advantage of their increasing power and began to function more like independent regimes. At the same time, natural causes such as droughts and famine in addition to internal corruptions and incompetent emperors contributed to the rise of a series of rebellions. The Huang Chao rebellion of the ninth century, which resulted in the destruction of both Chang'an and Luoyang took over 10 years to suppress. Although the rebellion was defeated by the Tang, it never really recovered from that crucial blow. A certain Zhu Wen (originally a salt smuggler) who had served under the rebel Huang had later surrendered to Tang forces, his military merit in betraying and defeating Huang's forces meant rapid military promotions for him.[22]

In 907, after almost 300 years in power, the dynasty was ended when this military governor, Zhu Wen (known soon after as Taizu of Later Liang), deposed the last emperor of Tang and took the throne for himself. He established his Later Liang Dynasty, which thereby inaugurated the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period.

Although cast in a negative light by many for usurping power from the Tang, Zhu Wen turned out to be a skilled administrator. He was also responsible for the building of a large sea-wall, along with new walls and roads for the burgeoning city of Hangzhou, which would later become the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty.[23]

Historiography about the Tang

The first classic work about the Tang is the Jiu Tang Shu (Old Book of Tang). Liu Xu (887-946 C.E.) of the Later Jin dynasty redacted it during the last years of his life. This was edited into another history (labelled Xin Tang shu, the New Book of Tang) in order to distinguish it, which was a work by the historian Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) and Song Qi (998-1061) of the Song Dynasty (between the years 1044 and 1060). Both of them were based upon earlier annals, yet those are now lost. (c.f. ![]() PDF). Both of them also rank among the Twenty-Four Histories of China. One of the surviving sources of the Jiu Tang shu, primarily covering up to 756 C.E., is the Tongdian, which Du You presented to the emperor in 801 C.E. The Tang period was again placed into the enormous universal history text of the Zizhi Tongjian, edited, compiled, and completed in 1084 by a team of scholars under the Song Dynasty Chancellor Sima Guang (1019-1086). This historical text, written with 3 million Chinese characters in 294 volumes, covered the history of China from the beginning of the Warring States (403 B.C.E.) until the beginning of the Song Dynasty (960 C.E.).

PDF). Both of them also rank among the Twenty-Four Histories of China. One of the surviving sources of the Jiu Tang shu, primarily covering up to 756 C.E., is the Tongdian, which Du You presented to the emperor in 801 C.E. The Tang period was again placed into the enormous universal history text of the Zizhi Tongjian, edited, compiled, and completed in 1084 by a team of scholars under the Song Dynasty Chancellor Sima Guang (1019-1086). This historical text, written with 3 million Chinese characters in 294 volumes, covered the history of China from the beginning of the Warring States (403 B.C.E.) until the beginning of the Song Dynasty (960 C.E.).

| Preceded by: Sui Dynasty |

Tang Dynasty 618 – 907 |

Succeeded by: Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms |

Other notes

- During the reign of the Tang the world population grew from about 190 million to approximately 240 million, a difference of 50 million.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, and James B. Palais. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006), 91.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, 93.

- ↑ 300 Tang Poems e-text online[1]. English translations from Witter Bynner. The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology. (New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 1929). University of Virginia. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Arthur F. Wright. Buddhism in Chinese History. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959), 88 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Wright 88" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Joseph Needham. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. (Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986), 319.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 473-475.

- ↑ Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, 95.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 122

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 123.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ebrey, Wallhall, Palais, 92.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 685-687.

- ↑ John S. Bowman. Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 104-105.

- ↑ Zhiba Tang. The influence of the sail on the development of the ancient navy. (Proceedings of the International Sailing Ships Conference in Shanghai, 1991), 61.

- ↑ Fuwei Shen. Cultural flow between China and the outside world. (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1986), 163.

- ↑ Frances Woods. Did Marco Polo go to China? (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), 143.

- ↑ Shen, 155.

- ↑ Louise Levathes. When China Ruled the Seas. (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 38.

- ↑ Pean Liu. Viewing Chinese ancient navigation and shipbuilding through Zheng He's ocean expeditions. (Proceedings of the International Sailing Ships Conference in Shanghai. 1991), 178.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 661.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 511.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Bowman, 105.

- ↑ Needham, 320.

- ↑ Needham, 321.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benn, Charles. 2002. China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. NY: Oxford University Press, 2002 ISBN 0195176650.

- Schafer, Edward H. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985 ISBN 0520054628.

- Bowman, John S. Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000 ISBN 9780231110051

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, and James B. Palais. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006. ISBN 9780618133840

- Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled the Seas. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1994 ISBN 0671701584

- Liu, Pean (1991). Viewing Chinese ancient navigation and shipbuilding through Zheng He's ocean expeditions. Proceedings of the International Sailing Ships Conference in Shanghai.

- Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd, 1986.

- Needham, Jospeh. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd, 1986.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd, 1986.

- Schafer, Edward H. The Vermilion Bird: T’ang Images of the South. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press, 1967.

- Shen, Fuwei Cultural flow between China and the outside world. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1986 ISBN 711900431X.

- Tang, Zhiba (1991). The influence of the sail on the development of the ancient navy. Proceedings of the International Sailing Ships Conference in Shanghai.

- Woods, Frances. Did Marco Polo go to China? Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0813389992.

- Wright, Arthur F. Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959.

- de la Vaissière, E. Sogdian Traders. A History. Leiden: Brill, 2005 ISBN 9004142525

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/200px-Jade_dragon_(Tang).jpg)