Teapot Dome scandal

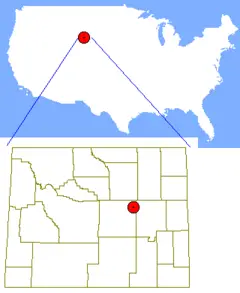

Teapot Dome was an oil reserve scandal that began during the administration of President Harding. Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills in California, and Teapot Dome in Wyoming, were tracts of public land that were reserved by previous presidents for emergency use by the U.S. Navy only when the regular oil supplies diminished.

The Teapot Dome oil field received its name because of a rock resembling a teapot that was located above the oil-bearing land. Many politicians and private oil interests had opposed the restrictions placed on the oil fields claiming that the reserves were unnecessary and that the American oil companies could provide for the U.S. Navy.

The Teapot Dome scandal became a parlor issue in the presidential election of 1924, but as the investigation had only just started earlier that year, neither party could claim full credit for exposing the wrongdoing. Eventually, when the Depression hit, the scandal was part of a snowball effect that damaged many of the big business Republicans of the 1920s. Increasingly, legal safeguards have been put in place to prevent corruption of this type, although the influence of big business and of lobbyists on government remains a matter of public concern, leading some to question whether politicians really represent their constituents, or those who, however legally, fund their campaigns. The problem is that some people will yield to temptation to profit from their political office, especially given the comparatively modest salaries that even U.S. Senators earn, which is less than what many lobbyists earn.[1]

Scandal

One of the public officials most avidly opposed to the reserves was New Mexico Republican Senator Albert B. Fall. A political alliance ensured his appointment to the Senate in 1912, and his political allies—who later made up the infamous Ohio Gang—convinced President Harding to appoint Fall as United States Secretary of the Interior in March of 1921.

The reserves were still under the jurisdiction of Edwin C. Denby, the Secretary of the Navy 1n 1922. Fall convinced Denby to give jurisdiction over the reserves to the Department of the Interior. Fall then leased the rights of the oil to Harry F. Sinclair of the original Sinclair Oil, then known as Mammoth Oil, without competitive bidding. Contrary to popular belief, this manner of leasing was legal under the General Leasing Act of 1920. Concurrently, Fall also leased the Naval oil reserves at Elk Hills, California, to Edward L. Doheny of Pan American Petroleum in exchange for personal loans at no interest. In return for leasing these oil fields to the respective oil magnates, Fall received gifts from the oilmen totaling about $404,000. It was this money changing hands that was illegal—not the lease itself. Fall attempted to keep his actions secret, but the sudden improvement in his standard of living prompted speculation.

On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal reported a secret arrangement in which Fall had leased the petroleum reserves to a private oil company without competitive bidding. Of course, Fall denied the claims, and the leases to the oil companies seemed legal enough on the surface. However, the following day, Wyoming Democratic Senator John B. Kendrick introduced a resolution that would set in motion one of the most significant investigations in the Senate's history. Wisconsin Republican Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. arranged for the Senate Committee on Public Lands to investigate the matter. At first, he believed Fall was innocent. However, his suspicions deepened after La Follette's office was ransacked.[2]

Despite the Wall Street Journal's report, the public did not take much notice of the suspicion, the Senate Committee Investigation, or the scandal itself. Without any proof and with more ambiguous headlines, the story faded from the public eye. However, the Senate kept investigating.

The investigation and its outcome

La Follette's committee allowed the investigation panel's most junior minority member, Montana Democrat Thomas J. Walsh, to lead what most expected to be a tedious and probably futile inquiry seeking answers too many questions.

For two years, Walsh pushed forward while Fall stepped backward, covering his tracks. The Committee continually found no evidence of wrongdoing, the leases seemed legal enough, and records simply kept disappearing mysteriously. Fall had made the leases of the oil fields appear to be legitimate, but his acceptance of the money was his undoing.

Any money from the bribes went to Fall's cattle ranch along with investments in his business. Finally, as the investigation was winding down and preparing to declare Fall innocent, Walsh uncovered one piece of evidence Fall had forgotten to cover up: Doheny's loan to Fall in November of 1921, in the amount of $100,000.

The investigation led to a series of civil and criminal suits related to the scandal throughout the 1920s. Finally in 1927 the Supreme Court ruled that the oil leases had been corruptly obtained and invalidated the Elk Hills lease in February of that year and the Teapot lease in October of the same year. The Navy regained control of the Teapot Dome and Elk Hills reserves as a result of the Court's decision. Another significant outcome was the Supreme Court case McGrain v. Daugherty which, for the first time, explicitly established Congress' right to compel testimony.

Albert Fall was found guilty of bribery in 1929, fined $100,000 and sentenced to one year in prison, making him the first Presidential cabinet member to go to prison for his actions in office. Harry Sinclair, who refused to cooperate with the government investigators, was charged with contempt, fined $100,000, and received a short sentence for tampering with the jury. Edward Doheny was acquitted in 1930 of attempting to bribe Fall.

Aftermath

The concentrated attention on the scandal made it the first symbol of government corruption in twentieth-century America. The scandal did reveal the problem of natural resource scarcity and the need to provide reserves against the future depletion of resources in a time of emergency. President Calvin Coolidge, in the spirit of his campaign slogan "Keep Cool with Coolidge," handled the problem very systematically and quietly, and his administration avoided damage to its reputation by blaming congressional Republicans for the scandal. Overall the Teapot Dome scandal came to represent the corruption of American politics over the preceding decades. This sort of thing had happened before; President Theodore Roosevelt had crusaded against this type of behavior twenty years earlier. Teapot Dome was just the first time this kind of corruption had been exposed nationally.

Warren G. Harding was not, directly, personally or otherwise, aware of the scandal. At the time of his death in 1923 he was just beginning to learn of problems deriving from the actions of his appointee when he undertook his Voyage of Understanding tour of the United States in the summer of 1923. Largely as a result of the Teapot Dome scandal, Harding’s administration has been remembered in history as one of the most corrupt to occupy the White House. Harding may not have acted inappropriately with regard to Teapot Dome, but he appointed people who did. This has resulted in Harding's name being forever linked to the infamous (and misnamed) Ohio Gang. It was revealed in 1923 that the FBI (then named the Bureau of Investigation) monitored the offices of members of Congress who had exposed the Teapot Dome scandal, including breaking in and wiretapping. When the agency's actions were revealed, there was a shakeup at the Bureau of Investigation, resulting in the appointment of J. Edgar Hoover, who would lead for 48 years as Director.

Following the exposure of Teapot Dome, Harding’s popularity plunged from the record highs it had been at throughout his term. The late President and First Lady Florence Kling Harding’s bodies were interred in the newly completed Harding Memorial in Marion, Ohio in 1927, but a formal dedication ceremony wouldn’t be held until 1930 when enough of the scandal had faded from the American consciousness.

Notes

- ↑ See MeKay, Emad. "POLITICS-US: The Best Democracy Money Can Buy," Inter-Press Service on the huge amount of money spent by lobbyists. POLITICS-US: The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.

- ↑ Senate Investigates the "Teapot Dome" Scandal Retrieved January 17, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hargrove, Jim. The Story of the Teapot Dome Scandal. Cornerstones of freedom. Chicago: Childrens Press, 1989. ISBN 9780516047225

- Weisner, Herman B. The Politics of Justice A.B. Fall and the Teapot Dome Scandal: a New Perspective. Albuquerque, NM: Creative Designs, 1988. ISBN 9781880047033

- Werner, M. R., and John Starr. Teapot Dome. Clifton, N.J.: A.M. Kelley, 1973. ISBN 9780678031797

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.