Thomas Eakins

| Thomas Eakins | |

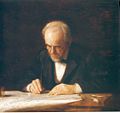

Self portrait (1902), National Academy of Design, New York. In 1894 the artist wrote: "My honors are misunderstanding, persecution & neglect, enhanced because unsought."[1] | |

| Birth name | Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins |

| Born | July 25 1844 Philadelphia |

| Died | June 25 1916 (aged 71) Philadelphia |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painting |

| Training | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Movement | Realism |

| Famous works | Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, 1871, The Gross Clinic, 1875, The Agnew Clinic, 1889 |

| Awards | National Academician |

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was a painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He was one of the greatest American painters of his time, an innovating teacher, and an uncompromising realist. He was also the most neglected major painter of his era in the United States.[2]

Eakins works upheld values of sincerity and truth, by depicting the subject's character in its truest form without presumed beauty and affectation. Indeed, the originality and individuality of his subjects were the expression of his concept of beauty. Such standards put him at odds with other artists of his time, which lends explanation to his ambiguous acceptance as a great American artist.

Early life

Eakins was born and lived most of his life in Philadelphia. He was the first child of Caroline and Benjamin Eakins, who moved to Philadelphia from Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in the early 1840's to raise their family. His father was a writing master and calligraphy teacher of Scots-Irish ancestry.[3] He influenced his son, Thomas, who, by age 12, demonstrated skill in precise line drawing, perspective, and the use of a grid to lay out a careful design.[4]

Eakins studied drawing and anatomy at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts beginning in 1861, and attended courses in anatomy and dissection at Jefferson Medical College from 1864-65. For a while he followed his father's profession and was listed in city directories as a "writing teacher."[5] His scientific interest in the human body led him to consider becoming a surgeon.[6] Eakins then studied art in Europe from 1866 to 1870, notably in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, being only the second American pupil of the French realist painter famous as a master of Orientalism.[7] He also attended the salon of Léon Bonnat, a realist painter who emphasized anatomical preciseness, a method later adapted by Eakins. While studying at L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he seems to have taken scant interest in the new Impressionist movement, nor was he impressed by what he perceived as the classical pretensions of the French Academy.

By age 24, he developed a strong desire for realistic artistic depictions of both anatomy and emotion. A trip to Spain for six months confirmed his admiration for the realism of artists such as Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera.[8] In Seville, in 1870, he painted Carmelita Requeña, a portrait of a seven year old gypsy dancer more freely and colorfully painted than his Paris studies, and in the same year attempted his first large oil painting, A Street Scene in Seville, wherein he first dealt with the complications of a scene observed outside the studio.[9] Although he failed to matriculate and showed no works in the salons, Eakins succeeded in absorbing the techniques and methods of French and Spanish masters, and he began to formulate his artistic vision which he demonstrated in his first major painting upon his return to America pronouncing, :I shall seek to achieve my broad effect from the very beginning."[10]

Work

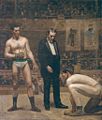

For the length of his professional career, from the early 1870s until his health began to fail some forty years later, Eakins worked exactingly from life, choosing as his subject the people of his hometown of Philadelphia. He painted several hundred portraits, usually of friends, family members, or prominent people in the arts, sciences, medicine, and clergy. Taken en masse, the portraits offer an overview of the intellectual life of Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; individually, they are incisive depictions of thinking persons. As well, Eakins produced a number of large paintings which brought the portrait out of the drawing room and into the offices, streets, parks, rivers, arenas, and surgical amphitheaters of his city. These active outdoor venues allowed him to paint the subject which most inspired him: The nude or lightly clad figure in motion. In the process he could model the forms of the body in full sunlight, and create images of deep space utilizing his studies in perspective.

Eakins's first works upon his return from Europe in 1870, included a large group of rowing scenes, eleven oils and watercolors in all, of which the first and most famous is The Champion Single Sculling, known also as Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871). Both his subject and his technique drew attention. His selection of a contemporary sport was "a shock to the artistic conventionalities of the city."[11]

. According to one prescient reviewer in 1876: "This portrait of Dr. Gross is a great work—we know of nothing greater that has ever been executed in America."[12]

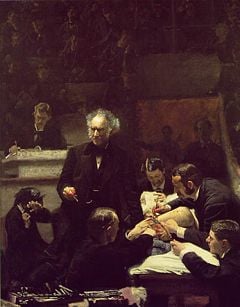

Eakins enjoyed painting portraits as an opportunity to reveal the character of an individual through the modeling of solid anatomical form.[13] Although artistically accomplished, he was not altogether commercially successful and received only a few commissions on his more than 250 portraits."[14]Indeed, his lack of sales may be explained by his preference for realism and his unique portrayal of character instead of the pretension and dramatization usually associated with artistic subjects. In The Gross Clinic (1875), a renowned Philadelphia surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, is seen presiding over an operation to remove part of a diseased bone from a patient's thigh. In the painting Dr. Gross is lecturing in an amphitheater crowded with students at Jefferson Medical College, onlookers to the graphic scene before them. Eakins spent nearly a year on the painting, again choosing a novel subject—the discipline of modern surgery, in which Philadelphia, at that time, was in the forefront. He initiated the project and may have had the goal of a large scale work befitting a showing at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. Though rejected for the Art Gallery, the painting was shown on the centennial grounds at an exhibit of a U.S. Army Post Hospital.

Of Eakins' later portraits, many took as their subjects women who were friends or students. Unlike most portrayals of women at the time, they are devoid of glamor and idealization, including his portrait of Maud Cook (1895), where the obvious beauty of the subject is noted with "a stark objectivity." The portrait of Miss Amelia C. Van Buren (ca. 1890), a friend and former pupil, suggests the melancholy of a complex personality, and has been called "the finest of all American portraits."[15] Even Susan Macdowell Eakins, a strong painter and former student who married Eakins in 1884, was not sentimentalized: Despite its richness of color, The Artist's Wife and His Setter Dog (ca. 1884-89) is a penetratingly candid portrait.[16]

Some of his most vivid portraits resulted from a late series done for the Catholic clergy, which included paintings of a cardinal, archbishops, bishops, and monsignors. As usual, most of the sitters were engaged at Eakins' request, and were given the portraits when Eakins had completed them. In portraits of His Eminence Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli (1902), Archbishop William Henry Elder (1903), and Monsignor James P. Turner (ca. 1906), Eakins took advantage of the brilliant vestments of the offices to animate the compositions in a way not possible in his other male portraits.

Teaching

No less important in Eakins' life was his work as a teacher. He returned to the Pennsylvania Academy in 1876, where he taught and rose to the position of director by 1882. Eakins gave only terse instruction to his students, allowing them to learn from example and find their own way. Most notable was his delight in teaching drawing of the human form, which involved studies of nude models and casts made from dissections. In addition, Eakins encouraged students to take up photography as an aid to anatomy and study of motion. He, himself, took keen interest in this new technology, adapting paintings from prints he took and creating series on aspects of the human form. Eakins is now seen as an innovator of motion photography.

Behavioral and sexual controversy shaped much of his career. He insisted on teaching men and women "the same," and—unusual for its time—used nude models in mixed-gender classes. One account includes posing nude for a female student in a private setting and pulling the loin cloth from a male model in a classroom full of females. Today, scholars see these controversies as caused by a combination of factors such as the bohemianism of Eakins and his artistic circle.

Legacy

Misunderstood and ignored in his lifetime, his posthumous reputation places him as "the strongest, most profound realist in nineteenth and early-twentieth century American art."[17]

Deeply affected by his dismissal from the Academy, Eakins's later career focused on portraiture. His steadfast insistence on his own vision of realism, in addition to his notoriety from his school scandals, combined to impact his income negatively in later years. Even as he approached these portraits with the skill of a highly trained anatomist, what is most noteworthy is the intense psychological presence of his sitters. However, it was precisely for this reason that his portraits were often rejected by the sitters or their families. [60] As a result, Eakins came to rely on his friends and family members to model for portraits. His portrait of Walt Whitman (1887-1888) was the poet's favorite.[18]

Late in life, Eakins did experience some recognition. In 1902, he was made a National Academician. In 1914, the sale of a portrait study of D. Hayes Agnew for the Agnew Clinic to Dr. Albert C. Barnes precipitated much publicity when rumors circulated that the selling price was fifty thousand dollars. In fact, Barnes bought the painting for four thousand dollars.[19]

In the year after his death, Eakins was honored with a memorial retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1917-18, the Pennsylvania Academy followed suit. Eakins' attitude toward realism in painting, and his desire to explore the heart of American life proved influential. He taught hundreds of students, among them his future wife, Susan Macdowell, African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Thomas Anshutz, who taught, in turn, Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan, and Everett Shinn, future members of the Ashcan School, and artistic heirs to Eakins's philosophy.[20] Even though Eakins struggled to make a living from his work, today he is regarded as one of the most important American artists of any period.

On November 11, 2006, the Board of Trustees at Thomas Jefferson University agreed to sell The Gross Clinic to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, for a record $68,000,000, the highest price for an Eakins painting as well as a record price for an individual American-made portrait.[21] On December 21, 2006, a group of donors agreed to pay $68,000,000 in order to keep the painting in Philadelphia. It will be displayed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Darrel Sewell, Thomas Eakins: Artist of Philadelphia (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982).

- ↑ Lloyd Goodrich, Thomas Eakins (Harvard University Press, 1982).

- ↑ Goodrich, Volume I, pages 1-4.

- ↑ Amy B. Werbel, Thomas Eakins (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001) ISBN 0-87633-142-8

- ↑ Amy B. Werbel, p. 10.

- ↑ John Canaday, "Thomas Eakins; Familiar truths in clear and beautiful language," Horizon, Volume VI, number 4, Autumn, 1964.

- ↑ H. Barbara Weinberg, Thomas Eakins (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001). ISBN 0-87633-142-8

- ↑ Updike, p. 72.

- ↑ Homer, p. 44.

- ↑ H. Barbara Weinberg, p. 23.

- ↑ Marc Simpson, Thomas Eakins (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001). ISBN 0-87633-142-8

- ↑ Sewell, p. 43.

- ↑ Goodrich, p. 57-8.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Canaday, p. 95.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Artist's Wife and his Setter Dog. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Goodrich, p. 285.

- ↑ Goodrich, p. 35.

- ↑ Homer, p. 249.

- ↑ Goodrich, p. 309.

- ↑ Kathryn Shattuck, Got Medicare? A $68 Million Operation, New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Henry. Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0195156684

- Canaday, John and Thomas Eakins. "Familiar truths in clear and beautiful language." Horizon. 6 (4) Autumn 1964.

- Goodrich, Lloyd. Thomas Eakins. Harvard University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-674-88490-6

- Homer, William Innes. Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art. Abbeville Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55859-281-4

- Johns, Elizabeth. Thomas Eakins. Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 0691002886

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney. The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0300108559

- Lubin, David. Acts of Portrayal: Eakins, Sargeant, James. Yale University Press, 1985. ISBN 0300032137

- Sewell, Darrel. Thomas Eakins: Artist of Philadelphia. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982. ISBN 0-87633-047-2

- Updike, John: Still Looking: Essays on American Art. Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4418-9

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. Thomas Eakins and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.

- Werbel, Amy. Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia. Yale University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780300116557.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Thomas Eakins Artchive.com.

- Thomas Eakins Ibiblio.org.

- Thomas Eakins Artcyclopedia.com.

- Thomas Eakins - Scenes from Modern Life Pbs.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.