Torture

Torture is any act by which severe physical or psychological pain is intentionally inflicted on a person. It can be used as a means of intimidation, as a deterrent, a punishment, or as a method for extracting information. Torture can also serve as a method of coercion or as a tool to control groups seen as a threat by governments. Throughout history, it has often been used as a method of inducing religious conversion or political "re-education."

Torture is almost universally considered to be a violation of human rights. Signatories of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions agree not to torture (enemy civilians and Prisoners of War (POWs) involved in armed conflicts. Signatories of the UN Convention Against Torture agree not to intentionally inflict severe pain or suffering on anyone in order to obtain information or a confession, to punish them, or to coerce them or a third person. These conventions and agreements notwithstanding, it is estimated by organizations such as Amnesty International that approximately two out of three countries fail to consistently abide by the spirit and letter of these statements. While the awareness that torture is a violation of the rights of each human being is a significant step in the establishment of a world of peace and harmony, this is only a step; full realization needs more than acknowledgment of the wrong, it needs a change in overall actions.

Etymology

The word torture derives from the Latin, tortura for torqu-tura, originally meaning "act of twisting." This root word means to apply torque, to turn abnormally, to distort, or to strain.

History of torture

Torture has been used by governments and authorities throughout history. In the Roman empire, for example, a slave's testimony was admissible only if it was extracted by torture, on the assumption that slaves could not be trusted to reveal the truth voluntarily.

Ancient and medieval philosophers—notably, Aristotle and Francis Bacon—were staunch champions of the utility of carefully monitored torture to the justice system. On the other hand, others such as Cicero and Saint Augustine argued against it as causing the innocent to be punished and to lie in order to escape it.

In much of Europe, medieval and early modern courts freely inflicted torture, depending on the accused's crime and the social status of the suspect. Torture was seen as a legitimate means for justice to extract confessions or obtain other information about the crime. Often, defendants sentenced to death would be tortured prior to execution so that they would have a last chance to disclose the names of their accomplices. Under the British common law legal system, a defendant who refused to plead would have heavier and heavier stones placed on their chest until a plea was entered or they suffocated. This method was known as peine forte et dure (French for "long and forceful punishment").

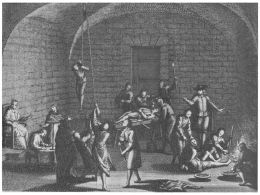

The use of torture was especially widespread throughout the Medieval Inquisition, although in Catholic countries it was putatively forbidden by papal bull in 1816. Within that time frame, men of considerable means delighted in building their own torture chambers, kidnapping innocent citizens of low birth off the streets, and subjecting them to procedures of their own invention, taking careful notes as to what techniques were more or less effective, and which body parts more or less receptive to pain.

In 1613, Anton Praetorius described the situation of the prisoners in the dungeons in his book Gründlicher Bericht über Zauberei und Zauberer (Thorough Report about Sorcery and Sorcerers). He was one of the first to protest against all means of torture.

Torture devices and methods

Throughout history tremendous ingenuity has been devoted to devising ever more effective and mechanically simpler instruments and techniques of torture. That those capable of applying such genius to the science of pain could be dangerous was not lost on the authorities. For example, after Perillos of Athens demonstrated his newly invented brazen bull, a hollow brass container that was designed to slowly roast a victim when a fire was lit under it, to Phalaris, Tyrant of Agrigentum, Perillos himself was immediately put inside to test it.

Some methods of torture practiced in the past were especially cruel. For example, scaphism, a method of execution practiced by the ancient Persians, required the naked victim to be firmly fastened within a back-to-back pair of rowboats and force-fed milk and honey to the point of severe diarrhea. Honey would be rubbed on his body so as to attract insects to the exposed appendages. The defenseless victim's feces accumulated within the container, attracting more insects, which would eat and breed within his exposed flesh.

One of the most common forms of medieval inquisition torture was known as strappado. The hands were bound behind the back with a rope, and the accused was suspended this way, dislocating the joints painfully in both arms. Under the method of mancuerda, a tight cord which was tied around the arms of the victim would be grasped by the torturer as they threw their weight backwards. The cord would then cut through skin and muscle right to the bone. Another torture method common at the time was the rack, which stretched the victim’s joints to breaking point, the forcible ingestion of massive quantities of water, or the application of red-hot pincers to fingers, toes, ears, noses, nipples, or even the penis.

Torture does not require complex equipment. Several methods need little or no equipment and can even be improvised from innocuous household or kitchen equipment. Methods such as consumption by wild animals (antiquity), impalement (Middle Ages), or confinement in iron boxes in the tropical sun (World War II Asia), are examples which required little more than readily available items.

Physical torture

Physical torture uses physical pain to inflict torment and is the most well known form of torture. There are countless methods of physical torture. These include physical violence, such as beating and whipping, burning, choking, cutting, scalping, boiling, branding, and kneecapping. Sexual violence, such as rape, incest, other forms of sexual assault, and genital mutilation, is also often employed as a form of physical torture.

Many methods of torture, such as foot roasting, foot whipping, and caning the feet, and torture devices such as the boot, the instep borer, and the foot press are intended for application to the feet. One of the key characteristics of a successful torture is that it can be prolonged almost indefinitely without endangering life, and this can best be achieved by directing the pain as far as physically possible from the brain and vital organs. The only part of the body that satisfies these twin criteria is the foot. Both the feet and the hands have clusters of nerve endings, which makes them especially effective body parts for the application of pain. Denailing, breaking bones and removing limbs, as well as application of the thumbscrews or tablillas are done to either the victim's hands or feet.

Other common methods of physical torture include aggravated tooth extraction, blinding with light or by abacination, force-feeding, and depriving the victim of oxygen, food, light, or sensory information. Even an action as innocuous as tickling or dropping water on the victim's forehead can be considered torture when used excessively.

The line between "torture method" and "torture device" is often blurred, particularly when a specifically named implement is but one component of a method. Some well-known torture devices include the breaking wheel, iron Maiden, Judas chair, pau de arara, pillory, and stocks.

Any method of execution which involves, or has the potential to involve, a great deal of pain or mutilation is considered to be a form of physical torture and unacceptable to many who support capital punishment. Some of these methods, if halted soon enough, may not have fatal effects. Types of execution that were common in the past, such as the guillotine, hanging, crucifixion, the gas chamber, and the firing squad, are classified as torture today. Even lethal injection, an official method of capital punishment in the United States, is considered to be torture if the anesthetic drugs fail to keep the paralyzed victim unconscious as he dies.

Other forms of physical torture include medical, electrical, and chemical torture. At times, medicine and medical practitioners have been drawn into the ranks of torturers, either to judge what victims can endure, to apply treatments which will enhance torture, or as torturers in their own right. An infamous example of the latter is Dr. Josef Mengele, known then by inmates of Auschwitz as the "Angel of Death."

Electrical torture is a modern method of torture or interrogation in which electrical shocks are applied to the body of the victim. For added effects, torturers may apply the shocks to sensitive areas such as the nipples or genitalia, or insert the electrode into the mouth, rectum, or vagina. Devices used in electrical torture can include the picana, the parrila, exposed live wires, medical clamps, and hand-cranked generators such as the Tucker telephone.

In the method of chemical torture, victims may be forced to ingest (or be injected with) chemicals or other products, such as broken glass, heated water, or soaps, which cause pain and internal damage. Irritating chemicals or products may be inserted into the rectum or vagina, or applied on the external genitalia. For example, cases of women being punished for adultery by having hot peppers inserted into their vaginas have been reported in India.

Psychological torture

This method of torture uses psychological pain to inflict torment and is less well known than physical forms of torture because its effects are often invisible to others. The torturer uses non-physical methods to induce mental or emotional pain in the victim. Since there is no international political consensus on what constitutes psychological torture, it is often overlooked and denied. Despite this, some of its most prominent victims, such as United States Senator John McCain, have stated that it is the ultimate form of torture.

Common methods of psychological torture include: Extended solitary confinement, being forced to witness or commit atrocities, being urinated on or covered with fecal matter, being kept in confined spaces, extended sleep deprivation, total sensory deprivation, forced labor, threats to family members, shaming or public humiliation, being stripped naked, forced participation in or witnessing of sexual activity, public condemnation, constant shouting, verbal abuse and taunting, alterations to room temperature, ball and chain, and shackling. Oftentimes physical and psychological torture can overlap.

A related form of torture called psychiatric torture uses psychiatric diagnoses and their associated treatments to torture sane people for political, religious, or familial reasons. It was a common form of torture used against political prisoners in the former Soviet Union. Mild forms of psychiatric torture have been used in the United States military against otherwise sane dissenting officers. Some religious groups who shun dissenting members, a form of psychological torture, also attempt to use psychiatric torture to falsely diagnosis mental disorders, so that ongoing shaming is possible.

Torture by proxy

In 2003, Britain's Ambassador to Uzbekistan, Craig Murray, made accusations that information was being extracted under extreme torture from dissidents in that country, and that the information was subsequently being used by Western, democratic countries which officially disapproved of torture.[1] The accusations did not lead to any investigation by his employer, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and he resigned after disciplinary action was taken against him in 2004. No misconduct by him was proven. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office itself is being investigated by the National Audit Office because of accusations of victimization, bullying, and intimidating its own staff.[2].

Murray later stated that he felt that he had unwittingly stumbled upon what has elsewhere been called "torture by proxy" or "extraordinary rendition." He thought that Western countries moved people to regimes and nations where it was known that information would be extracted by torture and then made available to them. This, he alleged, was a circumvention and violation of any agreement to abide by international treaties against torture. If it was true that a country was doing this and it had signed the UN Convention Against Torture, then that country would be in specific breach of Article 3 of that convention.

The term "torture by proxy" can, by logical extension, refer to the application of torture to persons other than the one from whom information or compliance is demanded. The ancient Assyrians, for example, specialized in brutally torturing children—flaying or roasting them alive, perhaps—before their parents' very eyes to wrest cooperation from the parents.

Torture murder

Torture murder is a term given to the commission of torture by an individual or small group as part of a sadistic agenda. Such murderers are often serial killers, who kill their victims by slowly torturing them to death over a prolonged period of time. Torture murder is usually preceded by a kidnapping, where the killer will take the victim to a secluded or isolated location.

Legal status of torture

On December 10, 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. Article 5 states "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment." Since that time the use of torture has been regulated by a number of international treaties, the most important of which are the United Nations Convention Against Torture and the Geneva Conventions.

United Nations Convention Against Torture

The "United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment" (UNCAT), came into force in June 1987. The most relevant articles are 1, 2, 3, and the first paragraph of article 16. At the present time, the UNCAT treaty has been signed by about half of all countries in the world. These are reproduced below:

- Article 1

- 1. Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

- 2. This article is without prejudice to any international instrument or national legislation which does or may contain provisions of wider application.

- Article 2

- 1. Each State Party shall take effective legislative, administrative, judicial, or other measures to prevent acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction.

- 2. No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.

- 3. An order from a superior officer or a public authority may not be invoked as a justification of torture.

- Article 3

- 1. No State Party shall expel, return ("refouler"), or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.

- 2. For the purpose of determining whether there are such grounds, the competent authorities shall take into account all relevant considerations including, where applicable, the existence in the State concerned of a consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights.

- Article 16

- 1. Each State Party shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article I, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. In particular, the obligations contained in articles 10, 11, 12, and 13 shall apply with the substitution for references to torture of references to other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

Potential loopholes

In Section 1, torture is defined as "severe pain or suffering," which means there are also levels of pain and suffering which are not severe enough to be called torture. Discussions regarding this area of international law are influenced by a ruling of the European Court of Human Rights(ECHR). Section 2 of the treaty states that if a state has signed the treaty without reservations, then there are "no exceptional circumstances whatsoever" where a state can use torture and not break its treaty obligations. However, the worst sanction that can be applied to a powerful country is a public record that they have broken their treaty obligations.[3] In certain exceptional cases, authorities in those countries may consider that, with plausible deniability, this is an acceptable risk to take since the definition of "severe" is open to interpretation. Furthermore, Section 16 of the treaty contains the phrase, "territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment," so if the government of a state authorizes its personnel to use such treatment on a detainee in territory not under its jurisdiction then it has not technically broken this treaty obligation.

Geneva Conventions

The four Geneva Conventions provide protection for those who fall into enemy hands. The third and fourth Geneva Conventions (GCIII and GCIV) are the two most relevant to the treatment of the victims of conflicts. Both treaties state in similarly worded articles that in a "non-international armed conflict persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms… shall in all circumstances be treated humanely" and that there must not be any "violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture or outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment."

Under GCIV most enemy civilians in an "international armed conflict will be 'Protected Persons.'" Under article 32, these persons have the right to protection from "murder, torture, corporeal punishments, mutilation and medical or scientific experiments…but also to any other measures of brutality whether applied by non-combatant or military agents."

GCIII covers the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs) in an international armed conflict. In particular, article 17 states that "No physical or mental torture, nor any other form of coercion, may be inflicted on prisoners of war to secure from them information of any kind whatever. Prisoners of war who refuse to answer may not be threatened, insulted or exposed to unpleasant or disadvantageous treatment of any kind. If a person is an enemy combatant in an international armed conflict, then they will have the protection of GCIII. If there is a question as to whether the combatant is unlawful or not, they must be treated as POW's "until their status has been determined by a competent tribunal" (GCIII article 5). Even if the tribunal decides that they are unlawful, they will still be protected under GCIV Article 5 and must be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial [for war crimes], shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial prescribed by the present Convention."

Geneva Conventions' additional protocols

There are two additional protocols to the Geneva Convention: Protocol I (1977), which broadens the definition of a lawful combatant in occupied territory to include those who carry arms openly but are not wearing uniforms and Protocol II (1977), which supplements the article relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts. These protocols clarify and extend the definitions of torture in some areas, but to date many countries, including the United States, have either not signed them or have not ratified them.

Other conventions

During the Cold War, in Europe a treaty called European Convention on Human Rights was signed. The treaty included the provision for a court to interpret it and Article 3, Prohibition of Torture, stated, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."

In 1978, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that techniques of "sensory deprivation" were not torture but were "inhuman or degrading treatment."

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights also explicitly prohibits torture and "cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment."

The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners states, "corporal punishment, punishment by placing in a dark cell, and all cruel, inhuman or degrading punishments shall be completely prohibited as punishments for disciplinary offenses."

Supervision of anti-torture treaties

In times of armed conflict between a signatory of the Geneva conventions and another party, delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) monitor the compliance of the signatories, which includes monitoring the use of torture.

The Istanbul Protocol (1999), an official UN document, is the first set of international guidelines for documentation of torture and its consequences.

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) "shall, by means of visits, examine the treatment of persons deprived of their liberty with a view to strengthening, if necessary, the protection of such persons from torture and from inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment," as stipulated in Article 1 of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[4]

Human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International and the Association for the Prevention of Torture, actively work to stop the use of torture throughout the world and publish reports on any activities they consider to be torture.

Domestic and national law

Countries which have signed the UNCAT have a treaty obligation to include the provisions into domestic law. The laws of many countries, therefore, formally prohibit torture. However, such legal provisions are by no means a proof that the signatory country does not actually use torture. To prevent torture, many legal systems have a right against self-incrimination or explicitly prohibit undue force when dealing with suspects.

Torture was abolished in England around 1640 (except peine forte et dure which was only abolished in 1772), in Scotland in 1708, in Prussia in 1740, in Denmark around 1770, in Russia in 1801.[5]

The French 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, of constitutional value, prohibits submitting suspects to any hardship not necessary to secure his person. Statute law explicitly makes torture a crime. In addition, statute law prohibits the police or justice from interrogating suspects under oath.

The United States includes this protection in the fifth amendment to its constitution, which in turn serves as the basis of the Miranda warning that is issued to individuals upon their arrest. Additionally, the US Constitution's eighth amendment expressly forbids the use of "cruel and unusual punishments," which is widely interpreted as a prohibition of the use of torture.

Torture in recent times

Even after the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, torture was still practiced in countries around the world. It remains a frequent method of repression in totalitarian regimes, terrorist organizations, and organized crime groups. In authoritarian regimes, torture is often used to extract confessions, whether true or not, from political dissenters, so that they admit to being spies or conspirators. Most notably, such forced confessions were extracted by the justice system of the Soviet Union (thoroughly described in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago).

Some Western democratic governments have on occasions resorted to torture, or acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, of people thought to possess information perceived to be vital for national security which cannot be obtained quickly by other methods. An example is the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp of the U.S. government, where detainees were subjected to extreme coercive methods. U.S. interrogation practices at Guantanamo have been identified as "torture" by the International Committee of the Red Cross (2004), the UN Commission on Human Rights (2006), and by nongovernmental organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

Many countries find it expedient from time to time to use torture techniques; at the same time, few wish to be described as doing so, either to their own citizens or international bodies. So a variety of devices are used to bridge this gap, including state denial, "secret police," "need to know," denial that given treatments are tortuous in nature, appeal to various laws (national or international), use of jurisdictional argument, claim of "overriding need," and so on. Torture has been a tool of many states throughout history and for many states it remains so today. Despite worldwide condemnation and the existence of treaty provisions that forbid it, torture is still practiced in many of the world's nations.[6]

Information extracted from torture

The use of torture has been criticized not only on humanitarian and moral grounds, but also on the grounds that evidence extracted by torture tends to be extremely unreliable and that the use of torture corrupts institutions which tolerate it.

The purpose of torture is often as much to force acquiescence on an enemy, or destroy a person psychologically from within, as it is to gain information, and its effects endure long after the torture itself has ended. In this sense, torture is often described by survivors as "never ending." Depending on the culture, torture has at times been carried on in silence (official denial), semi-silence (known but not spoken about), or openly acknowledged in public (in order to instill fear and obedience).

Since torture is, in general, not accepted in modern times, professional torturers in some countries tend to use techniques such as electrical shock, asphyxiation, heat, cold, noise, and sleep deprivation which leave little evidence, although in other contexts torture frequently results in horrific mutilation or death. Evidence of torture also comes from the testimony of witnesses.

Although information gathered by torture is often worthless, torture has been used to terrorize and subdue populations to enforce state control. This was a central theme of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Motivation to torture

It was long thought that only evil people would torture another human being. Research over the past 50 years suggests a disquieting alternative view, that under the right circumstances and with the appropriate encouragement and setting, most people can be encouraged to actively torture others. For example, the Stanford prison experiment and Milgram experiment showed that many people will follow the direction of an authority figure in an official setting, to the point of torture, even if they have personal uncertainty. The main motivations for this appear to be fear of loss of status or respect, and the desire to be seen as a "good citizen" or "good subordinate."

Both official and peer encouragement can incite people to torture others. The processes of dehumanization of victims, or disinhibition, are social factors that can also contribute to torture. Like many other procedures, once torture becomes established as part of internally acceptable norms under certain circumstances, its use often becomes institutionalized and self-perpetuating over time, as what was once used exceptionally for perceived necessity finds more reasons claimed to justify wider use. One of the apparent ringleaders of the Abu Ghraib prison torture incident, Charles Graner Jr., exemplified some of these when he was reported to have said, "The Christian in me says it's wrong, but the corrections officer in me says, 'I love to make a grown man piss himself.'"[7]

Effects of torture

Torture is often difficult to prove, particularly when some time has passed between the event and a medical examination. Many torturers around the world use methods designed to have a maximum psychological impact while leaving only minimal physical traces. Medical and Human Rights Organizations worldwide have collaborated to produce the Istanbul Protocol, a document designed to outline common torture methods, consequences of torture, and medico-legal examination techniques. Typically, deaths due to torture are shown in autopsy as being due to "natural causes." like heart attack, inflammation, or embolism due to extreme stress.[8]

For survivors, torture often leads to lasting mental and physical health problems. Physical problems can be wide-ranging, and can include musculo-skeletal problems, brain injury, post-traumatic epilepsy and dementia, or chronic pain syndromes. Mental health problems are equally wide-ranging; post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders are common.

Treatment of torture-related medical problems requires a wide range of expertise and often specialized experience. Common treatments are psychotropic medication such as SSRI antidepressants, counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, family systems therapy, and physiotherapy.

Notes

- ↑ Robin Gedye, The envoy silenced after telling undiplomatic truths, The Daily Telegraph, October 23, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Robert Winnett, "Foreign Office faces probe into 'manipulation,'" The Sunday Times, March 20, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Maggie Farley, Report: US Is Abusing Captives. Los Angeles Times, February 13, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Council of Europe, European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT). Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume IV: Mediaeval Christianity. A.D. 590-1073. Chapter VI. Morals And Religion: Page 80:The Torture. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Edward Peters, We Should Call Torture By Its Proper Name. History News Network, August 8, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Ted Olsen, Weblog: The Religious Side of the Abu Ghraib Scandal, Christianity Today Library, May 1, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Steven H. Miles, Medical Investigations of Homicides of Prisoners of War in Iraq and Afghanistan Medscape General Medicine 7(3) (2005). Retrieved May 22, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fiske, S.T., L.T. Harris, and A.J. Cuddy. "Social Psychology: Why Ordinary People Torture Enemy Prisoners." Science, 306 (2004): 1482-1483.

- Glasser, William. WARNING: Psychiatry Can be Dangerous to Your Health. Harper Paperbacks, 2004. ISBN 006053866X

- Hochschild, Adam. "What’s in a Word? Torture." New York Times, MAY 23, 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- Kellaway, Jean. The History of Torture & Execution: From Early Civilization through Medieval Times to the Present. Mercury Books, 2004. ISBN 1904668038

- Millet, Kate. The Politics of Cruelty: An Essay on the Literature of Political Imprisonment. W.W. Norton, 1994.

- Peters, Edward. Torture. Basil Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 0812215990

- Sampson, William. Confessions of an Innocent Man: Torture and Survival in a Saudi Prison. McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 2005. ISBN 0771079036

- Sontag, Susan. "Regarding the Torture of Others: Notes on what has been done—and why—to prisoners, by Americans." New York Times Magazine 42 (2004):24-29.

- Stover, Eric and Elena Nightingale. The Breaking of Bodies and Minds: Torture, Psychiatric Abuse, and the Health Professions. W. H. Freeman, 1985. ISBN 0716717336

External links

All links retrieved May 1, 2023.

- The Dark Art of Interrogation Mark Bowden article that covers modern methods of torture in The Atlantic.

- The Stain of Torture by Burton J. Lee III, former presidential physician to George H.W. Bush, Washington Post July 1, 2005.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.