Treaty

A Treaty is an agreement under international law that describes territorial or political agreements among states and international organizations. Such contracts are based on parties assuming obligations, under which they can be held liable under international law. Treaties may be multilateral, involving many parties, or bilateral, involving two parties which may be individuals or groups of states or organizations. Treaties are signed by heads of state and organizations, or their designated representatives with full authority.

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties is an agreement on the form, process, execution, amending, and ending treaty obligations. a treaty should be interpreted in good faith and to the full extent of its meaning. When all parties agree to a treaty's wording, then they recognize that the other side is a sovereign state and that the agreement is enforceable under international law. If a party has violated or breached its treaty obligations, the other parties may suspend or terminate the treaty. The United Nations Charter states that treaties must be registered with the UN before it can be enforced by its judiciary branch, the International Court of Justice.

Many treaties have been formulated at the conclusion of warfare, in which case they involve concessions by the defeated party and a commitment to honor them. Such treaties have been essential historically, due to the numerous conflicts among tribes and nations. However, for treaties to be effective and lead to lasting harmonious relationships, the concerns of all parties must be well represented. Treaties can work well when they represent a norm that is highly valued by all of the signers. If a treaty clearly reflects diverse concerns, the states that become party to the agreement recognize the value of complying with its terms and thus maintaining a harmonious relationship with all the parties involved.

Definition

A Treaty is a formal agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely states and international organizations. It is normally negotiated between plenipotentiaries (persons who have "full powers" to represent their government). A treaty may also be known as: (international) agreement, protocol, covenant, convention, or exchange of letters. The key feature that defines a treaty is that it is binding on the signing parties.

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties defines a treaty as "an international agreement concluded between states in written form and governed by international law," as well as affirming that "every state possesses the capacity to conclude treaties."[1]

Note that in United States constitutional law, the term "treaty" has a special meaning which is more restricted than its meaning in international law. U.S. law distinguishes what it calls "treaties" from "congressional-executive agreements" and "sole-executive agreements."[2] The distinctions concern their method of ratification: By two-thirds of the Senate, by normal legislative process, or by the President alone, respectively. All three classes are considered treaties under international law; they are distinct only from the perspective of internal United States law.

The fundamental purpose of a treaty is to establish mutually agreed upon norms of behavior in such areas as peace, alliance, commerce, or other relations between two or more states or international organizations. A treaty most often deals with the rights and duties of nations, but they may also grant certain rights to individuals.

Treaties can be loosely compared to contracts: Both are means by which willing parties assume obligations among themselves, and a party that fails to live up to their obligations can be held liable under international law for that breach. The central principle of treaty law is expressed in the maxim, pacta sunt servanda—"pacts must be respected."

The Vienna Convention

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) concerns the customary international law on treaties between states. It was adopted on May 22, 1969[3] and opened for signature on May 23, 1969. The Convention entered into force on January 27, 1980.[1] The VCLT had been ratified by 108 states as of May 2007; those that had not ratified it may still recognize it as binding upon them in as much as it is a restatement of customary law.

Customary international law comprises those aspects of international law that derive from custom. Coupled with general principles of law and treaties, custom is considered by the International Court of Justice, jurists, the United Nations, and its member states to be among the primary sources of international law. For example, laws of war were long a matter of customary law before they were codified in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, Geneva Conventions, and other treaties.

The vast majority of the world's governments accept in principle the existence of customary international law, although there are many differing opinions as to what rules are contained in it. Examples of items of customary international law are various international crimes—a state which carries out or permits slavery, genocide, war of aggression, or crimes against humanity is always violating customary international law. Other examples include the principle of non-refoulement, immunity of visiting foreign heads of state, and the right to humanitarian intervention.

Types of treaties

Multilateral treaties

A multilateral treaty establishes rights and obligations between each party and every other party. Multilateral treaties are often, but not always, open to any state; some may be regional in scope. Multilateral treaties are generally subject to formal ratification by the governments of each state that is a signatory.

Bilateral treaties

Bilateral treaties by contrast are negotiated between two parties, most commonly individual states, establishing legal rights and obligations between those two parties only. It is possible however for a bilateral treaty to have more than two parties; consider for instance the bilateral treaties between Switzerland and the European Union (EU) following the Swiss rejection of the European Economic Area agreement. Each of these treaties has 17 parties. These however are still bilateral, not multilateral, treaties. The parties are divided into two groups, the Swiss ("on the one part") and the EU and its member states ("on the other part"). The treaty establishes rights and obligations between the Swiss and the EU and the member states severally; it does not establish any rights and obligations amongst the EU and its member states.

Content

As well as varying according to the number of parties involved, treaties also differ with regard to their content.

- Political treaties

Political treaties deal with such issues as alliances, war, cessions of territory, and rectification of boundaries.

- Commercial treaties

Commercial treaties may govern fishing rights, navigation, tariffs, and monetary exchange.

- Legal treaties

Legal treaties are concerned with agreements regarding the extradition of criminals, patent and copyright protection, and so forth.

- Human-rights treaties

Human-rights treaties are based on a system of laws, both domestic and international, designed to promote the human rights of all individuals. Treaties governed by such laws include international covenants on economic, social, and cultural rights.

Execution and implementation

Treaties may be seen as "self-executing," in that merely becoming a party puts the treaty and all of its obligations in action. Other treaties may be non-self-executing and require "implementing legislation"—a change in the domestic law of a state party that will direct or enable it to fulfill treaty obligations. An example of a treaty requiring such legislation would be one mandating local prosecution by a party for particular crimes. If a treaty requires implementing legislation, a state may be in default of its obligations by the failure of its legislature to pass the necessary domestic laws.

Interpretation

The language of treaties, like that of any law or contract, must be interpreted when it is not immediately apparent how it should be applied in a particular circumstance. Article 31 of the VCLT states that treaties are to be interpreted in good faith according to "the ordinary meaning given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose." [4]

International legal experts also often invoke the "principle of maximum effectiveness," which interprets treaty language as having the fullest force and effect possible to establish obligations between the parties. Consent by all parties to the treaty to a particular interpretation has the legal effect of adding an additional clause to the treaty—this is commonly called an "authentic interpretation."

International tribunals and arbiters are often called upon to resolve substantial disputes over treaty interpretations. To establish the meaning in context, these judicial bodies may review the preparatory work from the negotiation and drafting of the treaty as well as the final, signed treaty itself.

Consequences of terminology

One significant part of treaty making is that signing a treaty implies recognition that the other party is a sovereign state and that the agreement being considered is enforceable under international law. Hence, nations are very careful about terming an agreement a treaty. For example, within the United States agreements between states are compacts and agreements between states and the federal government or between agencies of the government are memoranda of understanding.

Protocols

A "protocol" is generally a treaty or international agreement that supplements a previous treaty or international agreement. A protocol can amend the previous treaty, or add additional provisions. Parties to the earlier agreement are not required to adopt the protocol.

For example, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established a framework for the development of binding greenhouse-gas-emission limits, while the Kyoto Protocol contained the specific provisions and regulations later agreed upon.

Adding and amending treaty obligations

Reservations

Reservations are essentially caveats to a state's acceptance of a treaty. They are unilateral statements purporting to exclude or to modify the legal obligation and its effects on the reserving state.[5] These must be included at the time of signing or ratification—a party cannot add a reservation after it has already joined a treaty.

Originally, international law did not accept treaty reservations, rejecting them unless all parties to the treaty accepted the same reservations. However, in the interest of encouraging the largest number of states to join treaties, a more permissive rule regarding reservations emerged. While some treaties still expressly forbid any reservations, they are now generally permitted to the extent that they are not inconsistent with the goals and purposes of the treaty.

Procedure

Articles 19–22 of the Vienna Convention detail the procedures relating to reservations. Article 19 contains the requirements for a reservation to be legally valid: A state may not formulate a reservation if:

- The reservation is prohibited by the treaty.

- The treaty provides that only specified reservations, which do not include the reservation in question, may be made. This is often the case when during negotiations it becomes apparent that a certain provision in a treaty will not be agreed upon by all parties. Therefore, the possibility is given to parties not to agree with that provision but to agree with the treaty in general.

- In cases not falling under (1) or (2), the reservation is incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty. This is known as the "compatibility test."

Amendments

There are three ways an existing treaty can be amended. First, formal amendment requires states party to the treaty to go through the ratification process all over again. The re-negotiation of treaty provisions can be long and protracted, and some parties to the original treaty may not become parties to the amended treaty. Treaties can also be amended informally by the treaty executive council when the changes are only procedural, technical, or administrative (not principled changes). Finally, a change in customary international law (state behavior) can also amend a treaty, where state behavior evinces a new interpretation of the legal obligations under the treaty. Minor corrections to a treaty may be adopted by a procès-verbal; but a procès-verbal is generally reserved for changes to rectify obvious errors in the text adopted, such that it does not correctly reflect the intention of the parties adopting it.

Ending treaty obligations

Denunciation

"Denunciation" refers to the announcement of a treaty's termination. Some treaties contain a termination clause that specifies that the treaty will terminate if a certain number of nations denounce the treaty. For instance, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs' Article 41 specifies that the treaty will terminate if, as a result of denunciations, the number of Parties falls below 40.[6]

Treaties without termination clauses

Article 42 of The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states that "termination of a treaty, its denunciation or the withdrawal of a party, may take place only as a result of the application of the provisions of the treaty or of the present Convention."[7] Article 56 states that if a treaty does not provide for denunciation, withdrawal, or termination, it is not subject to denunciation or withdrawal unless:

- It is established that the parties intended to admit the possibility of denunciation or withdrawal

- A right of denunciation or withdrawal may be implied by the nature of the treaty

Any withdrawal under Article 56 requires 12 months' notice.

Withdrawal

Treaties are not necessarily permanently binding upon the signatory parties. As obligations in international law are traditionally viewed as arising only from the consent of states, many treaties expressly allow a state to withdraw as long as it follows certain procedures of notification. Many treaties expressly forbid withdrawal. Other treaties are silent on the issue, and so if a state attempts withdrawal through its own unilateral denunciation of the treaty, a determination must be made regarding whether permitting withdrawal is contrary to the original intent of the parties or to the nature of the treaty. Human-rights treaties, for example, are generally interpreted to exclude the possibility of withdrawal, because of the importance and permanence of the obligations.

Suspension and termination

If a party has materially violated or breached its treaty obligations, the other parties may invoke this breach as grounds for temporarily suspending their obligations to that party under the treaty. A material breach may also be invoked as grounds for permanently terminating the treaty itself.

A treaty breach does not automatically suspend or terminate treaty relations, however. The issue must be presented to an international tribunal or arbiter (usually specified in the treaty itself) to legally establish that a sufficiently serious breach has in fact occurred. Otherwise, a party that prematurely and perhaps wrongfully suspends or terminates its own obligations due to an alleged breach itself runs the risk of being held liable for breach. Additionally, parties may choose to overlook treaty breaches while still maintaining their own obligations towards the party in breach.

Treaties sometimes include provisions for self-termination, meaning that the treaty is automatically terminated if certain defined conditions are met. Some treaties are intended by the parties to be only temporarily binding and are set to expire on a given date. Other treaties may self-terminate if the treaty is meant to exist only under certain conditions.

A party may claim that a treaty should be terminated, even absent an express provision, if there has been a fundamental change in circumstances. Such a change is sufficient if unforeseen, if it undermined the “essential basis” of consent by a party, if it radically transforms the extent of obligations between the parties, and if the obligations are still to be performed. A party cannot base this claim on change brought about by its own breach of the treaty. This claim also cannot be used to invalidate treaties that established or redrew political boundaries.

Invalid treaties

There are several reasons an otherwise valid and agreed upon treaty may be rejected as a binding international agreement, most of which involve errors at the formation of the treaty.

Ultra vires treaties

A party's consent to a treaty is invalid if it had been given by an agent or body without power to do so under that state's domestic law. States are reluctant to inquire into the internal affairs and processes of other states, and so a “manifest” violation is required such that it would be “objectively evident to any State dealing with the matter." A strong presumption exists internationally that a head of state has acted within his proper authority.

Misunderstanding, fraud, corruption, coercion

Articles 46-53 of the Vienna Convention set out the ways that treaties can be invalidated—considered unenforceable and void under international law. A treaty will be invalidated due to either the circumstances by which a state party joined the treaty, or due to the content of the treaty itself. Invalidation is separate from withdrawal, suspension, or termination, which all involve an alteration in the consent of the parties of a previously valid treaty rather than the invalidation of that consent in the first place.

A state's consent may be invalidated if there was an erroneous understanding of a fact or situation at the time of conclusion, which formed the "essential basis" of the state's consent. Consent will not be invalidated if the misunderstanding was due to the state's own conduct, or if the truth should have been evident.

Consent will also be invalidated if it was induced by the fraudulent conduct of another party, or by the direct or indirect "corruption" of its representative by another party to the treaty. Coercion of either a representative, or the state itself through the threat or use of force, if used to obtain the consent of that state to a treaty, invalidates that consent.

Peremptory norms

A treaty is null and void if it is in violation of a peremptory norm. These norms, unlike other principles of customary law, are recognized as permitting no violations and so cannot be altered through treaty obligations. These are limited to such universally accepted prohibitions as those against genocide, slavery, torture, and piracy, meaning that no state can legally assume an obligation to commit or permit such acts.

Role of the United Nations

The United Nations Charter states that treaties must be registered with the UN to be invoked before it or enforced in its judiciary organ, the International Court of Justice. This was done to prevent the proliferation of secret treaties that occurred in the nineteenth and twentieth century. The Charter also states that its members' obligations under it outweigh any competing obligations under other treaties.

After their adoption, treaties as well as their amendments have to follow the official legal procedures of the United Nations, as applied by the Office of Legal Affairs, including signature, ratification, and entry into force.

Treaty strengths and weaknesses

Treaties can work when they represent a norm that is highly valued by all of the signers. If the treaty is well made to reflect diverse concerns, the states that become party to the agreement are satisfied with the terms and see no reason to defect. Treaties can be successful when their goals are simply and clearly expressed, and are measurable. States may remain confident in the agreement when there is a sound verification system in place, thus assuring that compliance will not threaten the tenets of the compact.

Treaties may not work for several reasons. States join treaties not to help make a better world or to help resolve an international problem, but only to join the treaty-signing event at the UN in order be seen as a multilateral player. Others are attracted to treaties for side benefits that are unrelated to core goals of the agreement, such as the supposed inalienable right of the party. Alternatively, states may be pressured by allies to join treaties, even though they are not that interested. Treaties may also fail if they are poorly made, giving signers opportunities to avoid compliance; if there is inherent vagueness and unfairness in the agreement; or if there is a lack of proper verification provisions. Treaties may fail because the bureaucracies intended to oversee them lose sight of their responsibility. Treaty failure may occur when there is an absence of sound compliance mechanisms, thus robbing the treaty of its intended powers and causing confusion among the parties. Noncompliance problems with treaties can sometimes be solved through improved implementation of existing instruments, including amending or adding to existing treaties, or supplementing the agreement with non-treaty mechanisms acceptable to all parties.

Notable treaties

- Peace of Augsburg (1555) between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and the forces of the Schmalkaldic League.

- Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the Thirty Years' War and the Eighty Years' War, and established the principle of the sovereignty of nations in use today.

- Treaty of Paris (1783) ended the American Revolutionary War.

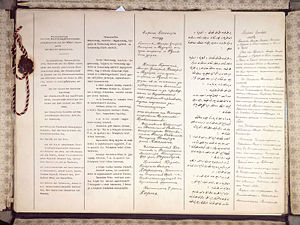

- Treaty of Ghent (1814) ended the War of 1812.

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) ended Russian involvement in World War I.

- Treaty of Versailles (1919) formally ended World War I.

- Munich Pact (1938) surrendered the Sudetenland to Germany.

- UN Charter (1945) established the United Nations.

- North Atlantic Treaty (1949) established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

- Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963) prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except underground.

- Camp David Accords (1978) agreement between Egypt and Israel reached at Camp David and witnessed by United States President Jimmy Carter.

- Maastrich Treaty (1992) established the European Union.

- Kyoto Protocol (1997) mandated the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 UN Treaty, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969, United Nations, 2005. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, Treaties and other International Agreements: the Role of the United States Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ UN Treaty, Law of treaties. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ United Naitons, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ United Nations, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Article 2 Sec. 1(d). Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ INCB, Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 (United Nations, 1972). Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ United Nations, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aust, Anthony. Modern Treaty Law and Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521591539.

- Brennan, Sean. Treaty. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1862875593.

- Gardiner, Richard K. Treaty Interpretation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0199277919.

- Goodman, R. Human Rights Treaties, Invalid Reservations and State Consent. The American Journal of International Law 96 (3) (July 2002): 531-560.

- Klabbers, J. Accepting the Unacceptable? A New Nordic Approach to Reservations to Multiltereral Treaties. 66 Nordic Journal of International Law 2000 66 (2000): 179-193.

- Korkella, Konstantin. New Challenges to the Regime of Reservations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. European Journal of International Law 13(2): 437-477.

- MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World. New York, NY: Random House, 2002. ISBN 978-0375508264.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- American Society of International Law

- European Union Treaties Office

- Reservations and Declarations made to the Council of Europe. Includes text of reservations.

- United Nations Treaty Section

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/250px-Signing_of_Treaty_of_Ghent_(1812).jpg)