Turkmenistan

| Türkmenistan Turkmenistan |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Independent, Neutral, Turkmenistan State Anthem "Garaşsyz, Bitarap Türkmenistanyň Döwlet Gimni" |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Ashgabat 37°58′N 58°20′E | |||||

| Official languages | Turkmen | |||||

| Language of interethnic communication |

Russian | |||||

| Demonym | Turkmen | |||||

| Government | Presidential republic Single-party state | |||||

| - | President | Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - | Declared | 27 October 1991 | ||||

| - | Recognized | 25 December 1991 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 491,210 km² [1](52nd) 188,456 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 4.9 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2021 estimate | 5,579,889[2] (116th) | ||||

| - | Density | 10.5/km² (221st) 27.1/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $112.659 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $19,526[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $42.764 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $7,411[3] | ||||

| Gini (1998) | 40.8[4] | |||||

| Currency | Turkmen new manat (TMT) |

|||||

| Time zone | TMT (UTC+5) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+5) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .tm | |||||

| Calling code | +993 | |||||

Turkmenistan (also known as Turkmenia) is a country in Central Asia that until 1991, was part of the Soviet Union as the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic.

With one-half of its irrigated land planted in cotton, Turkmenistan is in the world's top 10-15 producers. It also possesses the world's fifth largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources.

The area now known as Turkmenistan claims a history of conquest by other peoples and nations, the most recent being the Soviet Union in the twentieth century. Following its independence in 1991, a single-party system was adopted and President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov presided over a unique personality cult that masked widespread unemployment, poverty, and human rights abuses until his sudden death in December 2006. As is the case with many of the nations of the Commonwealth of Independent States (formerly under Soviet rule), much work is needed in order to recover from former abuses, both to its people and its environment.

Geography

The name Turkmenistan is derived from Persian, meaning "land of the Turkmen people." The name Turkmen, both for the people and for the nation itself, is said to derive from the period the Russians first encountered the people, who said "Tūrk-men," meaning "I am Tūrk."

The country is bordered by Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the southwest, Uzbekistan to the northeast, Kazakhstan to the northwest, and the Caspian Sea to the west. At 188,457 square miles (488,100 square kilometers), Turkmenistan is the world's 52nd-largest country. It is comparable in size to Cameroon, and somewhat larger than the U.S. state of California.

The center of the country is dominated by the Turan Depression and the Karakum Desert, which covers 135,135 square miles (350,000 square kilometers) or over 80 percent of the country. Shifting winds create desert mountains that range from six to 65 feet (two to 20 meters) in height, and may be several miles in length. Also common are smooth, concrete-like clay deposits formed by the repeated rapid evaporation of flood waters, and large marshy salt flats in many depressions, including the Kara Shor, which occupies 580 square miles (1500 square kilometers) in the northwest. The Sundukly Desert west of the Amu Darya river is the southernmost extremity of the Qizilqum Desert, most of which lies in Uzbekistan to the northeast.

Turkmenistan's average elevation is 100 to 220 meters above sea level. Its highest point is Mount Ayrybaba at 10,291 feet (3137 meters) in the Kugitang Range of the Pamir-Alay chain in the east, and its lowest point is in the Transcaspian Depression 328 feet (100 meters) below sea level. The Kopet Dag mountain range, along the southwestern border, reaches 9553 feet (2912 meters). The Turkmen Balkan Mountains in the far west and the Kugitang Range in the far east are the only other significant elevations.

Turkmenistan has a subtropical desert climate. Summers are long (from May through September), hot, and dry, while winters generally are mild and dry, although occasionally cold and damp in the north. Precipitation is slight throughout the country, with annual averages ranging from 12 inches (300mm) in the Kopet Dag to 3.14 inches (80mm) in the northwest. The average temperature of the hottest month, July, is 80°F- 86°F (27°C-30°C). The absolute maximum reaches 122°F (50°C) in Central and south-east Karakum. Lows reach 22°F (-5.5°C) in Daşoguz, on the Uzbek border. The almost constant winds are northerly, north-easterly, or westerly.

The most important river is the Amu Darya, which has a total length of 1578 miles (2540km) from its farthest tributary, making it the longest river in Central Asia. The Amu Darya flows across northeastern Turkmenistan, thence eastward to form the southern borders of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Damming and irrigation uses of the Amu Darya have had severe environmental effects on the Aral Sea, into which the river flows.

Desertification and pollution caused productivity to decline by 30 to 50 percent in the last decades of the twentieth century. Year-round pasturing of cattle has hastened the creation of desert areas. The Karakum and Qizilqum deserts are expanding at a rate surpassed only by that in the Sahara and Sahel regions of Africa. Between 3000 and 4000 square miles (8000 and 10,000 km²) of new desert appears each year in Central Asia.

Salinization, which forms marshy salt flats, is caused by leakage from canals, especially the Garagum Canal, where nearly half of the water seeps out into lakes and salt swamps.

Over-use of fertilizer contaminates the ground water. The most productive cotton lands in Turkmenistan (the middle and lower Amu Darya and the Murgap oasis) receive as much as 250 kilograms of fertilizer per hectare, compared with the average application of 30 kilograms per hectare. Only 15 to 40 percent of the chemicals can be absorbed by cotton plants, while the remainder washes into the soil and subsequently into the groundwater.

Cotton requires more pesticides and defoliants than other crops, and farmers misuse these chemicals. Local herdsmen, unaware of the danger of DDT, mix the pesticide with water and applied it to their faces to keep away mosquitoes. In the late 1980s, a drive began in Central Asia to reduce agrochemical usage. In Turkmenistan the campaign reduced fertilizer use 30 percent between 1988 and 1989.

History

The territory of Turkmenistan has been populated since ancient times, especially the areas near oasis of Merv. Tribes of horse-breeding Iranian Scythians drifted into the territory of Turkmenistan at about 2000 B.C.E., possibly from the Russian steppes and moved along the outskirts of the Karakum desert into Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. The scant remains that have been found point to some sparse settlements, including possibly early Neanderthals.

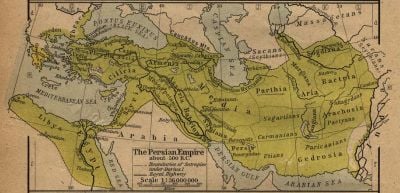

Persian and Macedonian conquests

The region's written history begins with its conquest by the Achaemenid Empire of ancient Persia (559 B.C.E.–330 B.C.E.), as the region was divided between the satrapys of Margiana, Khorezem and Parthia. Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.E.) conquered the territory in the fourth century B.C.E. on his way to India. Around that time the Silk Road was established as a trading route between Asia and the Mediterranean. In 330 B.C.E., Alexander founded the city of Alexandria near the Murgab River. Located on an important trade route, Alexandria later became the city of Merv (modern Mary). The ruins of Alexander's ancient city are still to be found. After Alexander's death his empire quickly fell apart.

Parthian Kingdom

About 150 years later Persia's Parthian Kingdom (150 B.C.E. and 224C.E.) established its capital in Nisa, now in the suburbs of the Turkmenistan capital, Ashgabat. At its height it covered all of Iran proper, as well as regions of the modern countries of Armenia, Iraq, Georgia, eastern Turkey, eastern Syria, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, the Persian Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. Nisa was believed to be founded by Arsaces I (who reigned c. 250–211 B.C.E.). Excavations at Nisa have revealed substantial buildings, mausoleums and shrines, many inscribed documents, Hellenistic art works, and a looted treasury. The Parthian Kingdom succumbed in 224 C.E. to the Sasanid rulers of Persia.

Göktürks

The Göktürks or Kök-Türks were a Turkic people who, under the leadership of Bumin Khan (d. 552) and his sons, established the first known Turkic state around 552 C.E. in the general area of territory that had earlier been occupied by the Huns, and expanded rapidly to rule wide territories in Central Asia. The Göktürks originated from the Ashina tribe, an Altaic people who lived in the northern corner of the area presently called the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. They were the first Turkic tribe to use the name "Türk."

Arab conquest

By the seventh century, Merv and Nisa became centers of sericulture (silkworms), and a busy caravan route, connecting China and the city of Baghdad (in modern Iraq), passed through Merv. Beginning in 651, the Arabs organized periodic marauding raids deep into the region. Central Asia came under Arab control by the early eighth century and was incorporated into Islamic Caliphate divided between provinces of Mawara'un Nahr and Khurasan. The Arabs brought Islam. The city of Merv was occupied by lieutenants of the caliph Uthman ibn Affan, and was the capital of Khorasan. Using this city as their base, the Arabs subjugated Balkh, Bokhara, Fergana and Kashgaria, and penetrated into China as far as the province of Kan-suh early in the eighth century.

Abu Muslim (d. 750) declared a new Abbasid dynasty at Merv, in February 748, and set out from the city to conquer Iran and Iraq and establish a new capital at Baghdad. The goldsmith of Merv famously challenged Abu Muslim to do the right thing and not make war on fellow Muslims. The goldsmith was put to death. In the latter part of the eighth century, Merv became known as the center of heretical propaganda preached by al-Muqanna "The Veiled Prophet of Khorasan." Merv, like Samarkand and Bukhara, was one of the great schools of learning, and the celebrated historian Yaqut studied there. Merv produced a number of scholars in Islamic law, Hadith, history, literature, and the like. In 874 Arab rule in Central Asia came to an end.

Conquest of Merv

By 780, the eastern parts of the Syr Darya were ruled by the Karluk Turks and the western region (Oghuz steppe) was ruled by the Oghuz Turks. In 1040, the Seljuk Turks crossed the Oxus from the north, and having defeated Masud, Sultan of Ghazni, raised Toghrul Beg, grandson of Seljuk, to the throne of Persia, founding the Seljukid dynasty, with its capital at Nishapur. A younger brother of Toghrul, Daud, took possession of Merv and Herat. Toghrul was succeeded by his nephew Alp Arslan (the Great Lion), who was buried at Merv. During the reign of Sultan Sanjar, in the middle of the eleventh century, Merv was overrun by the Turkish tribes of the Ghuzz from beyond the Oxus. After mixing with the settled peoples in Turkmenistan, the Oguz living north of the Kopet-Dag Mountains gradually became known as the Turkmen people. In 1157, Seljuk rule came to an end in Khorasan, and the Turkic rulers of Khiva took control, under the title of Khwarezmshahs. The Turkmen became independent tribal federation.

Mongols and Timurids

In 1221, Mongol warriors swept across the region from their base in eastern Asia. Under the command of Genghis Khan, the Mongols conquered Khorasan and burned the city of Merv to the ground. The Mongol leader ordered the massacre of Merv's inhabitants as well as the destruction of the province's farms and irrigation works. The Turkmen who survived the invasion retreated north to the plains of Kazakhstan or eastward to the shores of the Caspian Sea.

Small, semi-independent states arose under the rule of the region's tribal chiefs later in the fourteenth century. In the 1370s, the Mongol leader Timur "The Lame" (known as Tamerlane in Europe), a self-proclaimed descendant of Genghis Khan, conquered Turkmen states once more and established the short-lived Timurid Empire, which collapsed after Timur's death in 1405, when Turkmens became independent once again.

Turkmen traditions coalesce

As the Turkmen migrated from the area around the Mangyshlak Peninsula in contemporary Kazakhstan toward the Iranian border region and the Amu Darya river basin, tribal Turkmen society further developed cultural traditions that would become the foundation of Turkmen national consciousness. Persian shahs, Khivan khans, the emirs of Bukhara and the rulers of Afghanistan fought for control of Turkmenistan between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Popular epics such as Korogly and other oral traditions took shape during this period which could be taken as a beginning of Turkmen nation. The poets and thinkers of the time, such as Devlet Mehmed Azadi and Magtymguly Pyragy, became a voice for an emerging nation, calling for unity, brotherhood and peace among Turkmen tribes. Magtymguly is venerated in Turkmenistan as the father of the national literature.

Russian conquest

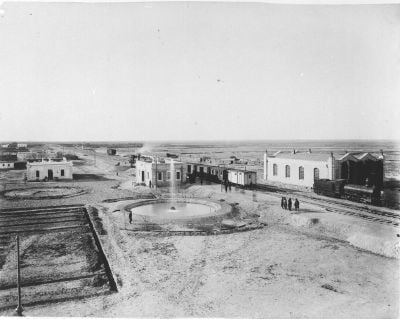

The Russian Empire began to spread into Central Asia during the Great Game, a period generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, during which Britain and Tsarist Russia competed for influence in Central Asia. Turkmen people resisted Russian advances more than other countries in the region, until their defeat at the battle of Gök Tepe in 1881, when thousands of women and children were slaughtered. The Russian army continued fighting until it had secured Merv (Mary) in 1884. Slowly, Russian and European cultures were introduced. The Russians ended slavery, brought the Transcaspian Railroad, and brought Russian colonists. This was evident in the architecture of the newly formed city of Ashgabat, which became the capital.

Soviet rule

The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia and subsequent political unrest led to the declaration of the area as the Turkmen SSR, one of the six republics of the Soviet Union in 1924, assuming the borders of modern Turkmenistan. The tribal Turkmen people were encouraged to become secular and adopt Western-style clothing. The Turkmen alphabet was changed from the traditional Arabic script to Latin and finally to Cyrillic. The Turkmen people continued their nomadic lifestyle until 1948. Nationalist organizations existed during the 1920s and the 1930s.

Independence

When the Soviet Union began to collapse, Turkmenistan and the rest of the Central Asian states heavily favored maintaining a reformed version of the state, mainly because they needed the economic power and the common markets of the Soviet Union to prosper. Turkmenistan declared independence on October 27, 1991, one of the last republics to secede. Saparmurat Niyazov became chairman of the Supreme Soviet in January 1990, and was elected as the country's first president that October. He was the only candidate in Turkmenistan's first presidential elections in 1992. A 1994 plebiscite extended his term to 2002, and parliament extended his term indefinitely in 1999.

He styled himself as a promoter of traditional Muslim and Turkmen culture, calling himself "Turkmenbashi," or "leader of the Turkmen people." But he quickly became notorious in the Western world for his dictatorial rule and extravagant cult of personality. The extent of his power was increased in the early 1990s, and in 1999, he became President-for-Life. Russian-Turkmeni relations suffered under his rule.

An attempt was made on the president’s life in November 2002, when his motorcade was attacked. A total of 46 people were found guilty of trying to assassinate Niyazov, who died unexpectedly on December 21, 2006, leaving no heir-apparent and an unclear line of succession. Deputy prime minister Gurbanguly Berdimuhammedow was named acting president, and was elected president in his own right on February 11, 2007, in elections condemned by international observers as fraudulent. Berdymukhamedov embarked on reform of the education, health care, and pension systems, and began to reduce the Niyazov personality cult.

Government and politics

The politics of Turkmenistan take place in the framework of a presidential republic, with the president both head of state and head of government. Turkmenistan has a single-party system. Under the 1992 constitution, the president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. The president appoints a cabinet of ministers.

There are two parliamentary bodies. A unicameral People's Council, or Halk Maslahaty, a supreme legislative body of up to 2500 delegates, some of whom are elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and some of who are appointed, meets at least yearly. A unicameral Assembly, or Mejlis, of 50 seats (scheduled to be increased to 65), comprises members elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms. All 50 elected officials are members of the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan and were pre-approved by the president.

In late 2003, a law was adopted reducing the powers of the Mejlis and making the Halk Maslahaty the supreme legislative organ, which can legally dissolve the Mejlis. The president may participate in the Mejlis as its supreme leader. The Mejlis can no longer adopt or amend the constitution or announce referendums or its elections. Since the president is both the "Chairman for Life" of the Halk Maslahaty, and the supreme leader of the Mejlis, the 2003 law has the effect of making him the sole authority of both the executive and legislative branches of government.

Only one political party, the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan, is legally allowed to hold power. Formal opposition parties are outlawed. Unofficial, small opposition movements exist underground or in foreign countries, and the two most prominent opposition groups in exile have been National Democratic Movement of Turkmenistan (NDMT) and the United Democratic Party of Turkmenistan (UDPT).

An independent judiciary is required by the constitution, but the president appoints all judges for a term of five years. The court system is similar to that under Soviet rule. There are 61 district and city courts, six provincial courts, a Supreme Court, and a supreme economic court for disputes between business enterprises and ministries. Military courts were abolished in 1997. Decisions of lower courts may be appealed higher courts. Although defendants in criminal cases have the right to a public trial and to defense counsel, these rights are often denied. There are few private lawyers. Defendants may seek clemency. The president releases large numbers of prisoners in periodic amnesties. The legal system is based on civil law.

Türkmen customary law, or adat is the guideline of etiquette and behavior, and Islamic law, Şarigat, gives guidance on inheritance, property ownership, marriage, family life, respect for elders, hospitality, and tribal and clan identity.

Human rights

Any opposition to the government is considered treason and punishable by life imprisonment. Turkmenistan has many political prisoners, the most well-known of whom are Batyr Berdiev, Yazgeldy Gundogdiyev, Boris Shikhmuradov, and Mukhametkuli Aimuradov. Arbitrary arrests and mistreatment of detained persons are common in Turkmenistan, as is torture to obtain confessions. In 2004, border guards shot and killed six people who were allegedly illegally crossing the border from Iran.

The Turkmen government's decision to cancel a dual-citizenship agreement with Russia in 2003 prompted thousands of ethnic Russians to leave Turkmenistan as they lost their property. For those who remained, estimated at around 100,000, all Soviet-time diplomas, certificates and other official documents that were issued outside the Turkmen SSR had their status nullified, effectively limiting drastically the people's access to work.

Controversy surrounds the death in custody of Radio Free Europe journalist Ogulsapar Muradova. According to Reporters Without Borders' 2006 World Press Freedom Index, Turkmenistan had the second worst press freedom conditions in the world, behind North Korea. It is considered to be one of the "10 Most Censored Countries." Each broadcast begins with a pledge that the broadcaster's tongue will shrivel if he slanders the country, flag, or president. This pledge is recited by students at the beginning of the school day, and at the beginning of virtually all official meetings. While he was president, Niyazov controlled all Turkmen media outlets and personally appointed journalists. News anchors, both men and women, were prevented from wearing any sort of makeup after Niyazov discovered he was unable to tell the difference between them when the presenters wore makeup.

Niyazov banned playing of video games, listening to car radios, performing opera and ballet, smoking in public, and even growing facial hair. Niyazov ordered the closure of all libraries outside the capital of Ashgabat in the belief that all Turkmen are illiterate.

Any act of homosexuality in Turkmenistan is punishable by up to five years in prison.

Cult of personality

Turkmenistan is dominated by a pervasive cult of personality extolling the late president as “Türkmenbaşy” ("Leader of all Turkmen"), a title he assumed in 1993. His face adorns many everyday objects, from banknotes to bottles of vodka. The logo of Turkmen national television is his profile. Many institutions are named after his mother. All watches and clocks made must bear his portrait printed on the dial-face. A giant 15-meter (50 feet) tall gold-plated statue of him stands on a rotating pedestal in Ashgabat, so it will always face into the sun and shine light onto the city.

A slogan popular in Turkmen propaganda is "Halk! Watan! Türkmenbashi!" ("People! Motherland! Leader!") Niyazov renamed the days of the week after members of his family and wrote the new Turkmen national anthem/oath himself.

His book, Ruhnama (or Rukhnamaor “The Book of the Soul”), which is revered in Turkmenistan almost like a holy text, has been translated into 32 languages and distributed for free among international libraries. It is a combination of autobiography, historical fiction, and spiritual guidebook. The text is composed of many stories and poems, including those by Sufi poet Magtymguly Pyragy.

Niyazov issued the first part of the work in 2001, saying it would "eliminate all shortcomings, to raise the spirit of the Turkmen." Niyazov issued the second part, which covers morals, philosophy, and life conduct, in 2004. Ruhnama is imposed on religious communities, is the main component of education from primary school to university. Knowledge of the text – up to the ability to recite passages from it exactly – is required for passing education exams, holding any state employment, and to qualify for a driving license. Public criticism of or even insufficient reverence to the text was seen as the equivalent to showing disrespect to the former president himself, and harshly punished by dispossession, imprisonment or torture of the offender or the offender's whole family if the violation was grave enough.

In March 2006 Niyazov was recorded as saying that he had interceded with Allah to ensure that any student who reads the book three times would automatically get into paradise. An enormous mechanical replica of the book is located in the capital; every night at 8 P.M. it opens and passages are recited with accompanying video.

Military

Turkmenistan’s army had 21,000 personnel in 2003, and its air force had 4300 personnel. For naval defense, the country has a joint arrangement with Russia and Kazakhstan in the Caspian Sea flotilla. Border security was increased in 1994, when Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia formed the Caspian Border Patrol Force. All men aged 18 or over are liable to military service. Turkmenistan spends about 1.2 per cent of GDP on defense.

International relations

Turkmenistan belongs to the Commonwealth of Independent States, the United Nations, the Partnership for Peace, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Economic Cooperation Organization, the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the Group of 77, and the Non-Aligned Nations.

Economy

Turkmenistan is largely a desert country with nomadic cattle raising, intensive agriculture in irrigated oases, and huge natural gas and petroleum resources. One-half of its irrigated land is planted in cotton, placing the country in the top 10-15 producers. It possesses the world's fifth largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources.

Until the end of 1993, Turkmenistan had experienced less economic disruption than other former Soviet states because of higher prices for oil and gas. But in 1994, the Russian government's refusal to export Turkmen gas, and the mounting gas debts of its customers in the former Soviet Union, contributed to a sharp fall in industrial production and caused the budget to shift from surplus to deficit. Poor harvests in the early 2000s led to an almost 50 percent decline in cotton exports.

With an authoritarian ex-Communist regime in power and a tribally based social structure, Turkmenistan has taken a cautious approach to economic reform, hoping to use gas and cotton sales to sustain its inefficient economy.

Ownership has been an issue. Traditional ownership land and water were in common, by villages and nomadic groups. Under Soviet rule, the government owned all land and property. In 1995, the government enabled leases of farmland, preferably to groups, and revived the traditional position of mirap (the post overseeing water distribution and management). Legalities for foreign ownership of land and buildings were being settled in 2007. However, privatization goals remained limited.

Two-thirds of Turkmen gas goes through the Russian state-owned Gazprom. Between 1998 and 2005, Turkmenistan suffered from the lack of adequate export routes for natural gas, and from extensive short-term external debt. At the same time, however, the value of total exports has risen by about 15 percent each year from 2003-2006 because of higher international oil and gas prices.

President Niyazov extensively renovated cities, Ashgabat in particular. Corruption watchdogs voiced concern over the management of Turkmenistan's currency reserves, most of which are held in off-budget funds such as the Foreign Exchange Reserve Fund in the Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt, according to a 2006 report by London-based Global Witness. Since 2003, electricity, natural gas, water and iodized salt were to be provided free of charge to citizens up to 2030. However, shortages were frequent.

Widespread internal poverty, a poor educational system, government misuse of oil and gas revenues, and Ashgabat's unwillingness to adopt market-oriented reforms are obstacles to prosperity. Turkmenistan's economic statistics are state secrets, and GDP and other figures are subject to wide margins of error. President Berdymukhammedov’s election platform included plans to build a gas line to China, to complete the Amu Darya railroad bridge in Lebap province, and to create special border trade zones in southern Balkan province.

Exports totalled $5.421-billion in 2006. Export commodities included gas, crude oil, petrochemicals, cotton fiber, and textiles. Export partners included Ukraine 42.8 percent, Iran 14.8 percent, Hungary 5.3 percent.

Imports totalled $3.936-billion in 2006. Import commodities included machinery and equipment, chemicals, and foodstuffs. Import partners included United Arab Emirates 12.7 percent, Azerbaijan 11.1 percent, United States 9.6 percent, Russia 9.1 percent, Ukraine 7.6 percent, Turkey 7.3 percent, Iran 6.2 percent, and Germany 5.4 percent.

In 2004, the unemployment rate was estimated to be 60 percent; the percentage of the population living below the poverty line was thought to be 58 percent a year earlier. The unreliable per capita GDP estimate for 2005 was $8098, or 73rd on a list of 194 countries.

Demographics

Turkmen were not settled in cities and towns until the Soviet system of government which restricted freedom of movement and collectivized the nomadic herdsmen by the 1930s. Many pre-Soviet cultural traits have survived, and since independence in 1991, a cultural revival has occurred with the return of moderate Islam and celebration of Novruz, an Iranian tradition for New Year's Day.

Ethnicity

Türkmen descend from the Oguz, a confederation of tribes that migrated out of the Gök Türk empire (fifth to eighth centuries) near Mongolia. Ethnic Turkmen make up the majority of the population, with smaller numbers of Russians, Uzbeks, Azerbaijanis, Armenian, and Tatars.

Türkmen are related to other Turkic peoples, the Uighurs, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Kirghiz, Tatars, Başkurts, Azerbaijanis, and those in Turkey. For centuries, the Türkmen were a fragmented group of tribes that alternately co-operated or fought against each other. They were the ethnic base of the Seljuk and Ottoman empires, as well as modern Azerbaijan and Turkey. They were magnificent horsemen and warriors who raided their neighbors, especially Persia, for slaves and wealth.

Religion

Türkmenistan remained secular after independence, despite a surge of interest in Islam. The majority of Türkmen are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school. When Arab and Persian invasions brought Islam to Central Asia in the seventh and eighth centuries, nomadic Turks mixed aspects of Islam with elements of Zoroastranism (the celebration of Novruz), and retained the name of the sky god Gök for the words blue and green. Religious leaders are called mollas. The oldest man in a group leads prayer.

In 1992, the government established Turkmenistan’s own highest religious authority, known as the Kazyÿat, separate from the Central Asian Müftiÿat, to promote Islam as an aspect of national culture. Secularism and atheism remain prominent for many Turkmen intellectuals who favor moderate social changes and often view extreme religiosity and cultural revival with distrust.

Language

The Türkmen language, a member of the East Oghuz branch of Turkic, is spoken by the majority percent of the population; other languages include Russian, Uzbek language, Balochi language. Türkmen is closest to the language spoken in Turkey and Azerbaijan, although all Turkic dialects are mutually understandable. Türkmen writers used a Turkic literary language (Chagatai) until the eighteenth century when a Türkmen literary language began to emerge. The modern language was developed in the 1920s as a result of Soviet interest in creating a national literary language. There are many borrowed words from Arabic, Persian, and Russian, especially for technical and scientific terms.

Men and women

In the traditional nomadic lifestyle, men hunted, tended the herds, and kept the horses, while women cooked, tended the home, and made textiles. Women were always considered equal partners, and the last independent Türkmen leader was a woman, Güljamal Hatun. Under Soviet rule, women could attain higher education, began to work outside the home, and were represented in a wide range of occupations, including politics. Men tend to work in heavy industry and with livestock. Men and women may sit and eat together, although during a social event, they may remain in separate rooms.

Marriage and the family

Türkmen marry in their early twenties, and expect to have a baby in the first year of marriage. The groom's parents can demand a divorce if they suspect that the bride is infertile. A bride price (galyñ) is paid. A nomadic tradition of wife stealing is still practiced. A man may kidnap any unmarried girl 15 years of age and over. The girl spends a night alone with the man. The next day she is taken to meet her mother-in-law, who ties a scarf around the girl's head show she is married. A Türkmen wedding is a festive occasion characterized by historic Turkic rituals. Polygamy is not common. The youngest son remains (with his wife and family) with his parents to care for them in their old age, and inherits the home upon their deaths. Many Turkmen live in extended families, especially in rural areas.

There is a complex kinship system with terms to refer to gender, seniority, and to indicate whether a person is related on the mother's or father's side. Türkmen families, which are close, belong to clans, and to tribes, and relationships within and between these govern loyalties, economics, marriages, and even migration. Most marry within the tribe, and jobs are frequently filled along tribal lines.

Male babies are circumcised in a special ceremony. Women are responsible for raising the children, although fathers teach their sons about labor, ethics, and etiquette. A young girl prepares the items necessary for her marriage and practices cooking, sewing, embroidery, and textile making.

Education

Education was in the Islamic tradition before the state-funded Soviet system, which remained after independence. There are kindergartens and elementary schools, and graduation at eighth grade is mandatory. Enrollment rates for secondary education are about 90 per cent, and 25 to 30 per cent of those are eligible for further education. Seventy-seven percent of schools teach in Türkmen, and 16 percent in Russian. The role of English has expanded. There are several higher institutes in Aşgabat, and there is one teacher training college in Türkmenabad. The high standard of literacy is estimated at 98 per cent, but all institutions lack financial security, are short of up-to-date text books, and have dilapidated buildings and under-trained teachers.

Class

A traditional distinction was between nomadic pastoralists and settled agriculturalists, although tribal affiliation was the main marker. Under Soviet rule, an elite developed among the party bosses and some writers, artists, and scholars, although privileged individuals (those with summer homes in rural areas) could quickly fall out of favor as the political wind shifted. Changes in agriculture, the oil industry and the business world have created opportunities, especially younger Turkmen people who know English. Tribal loyalties and personal contacts remain important.

Culture

Turkmen have a prominent horse culture, and the “Akhal-Teke” breed of horse is a national symbol. Noted for their speed and for endurance on long marches, these "golden-horses" have adapted to severe climatic conditions and are thought to be one of the oldest surviving breeds. A Soviet law outlawing private ownership of livestock in the 1920s, and attempts to erase the Akhal-Teke through breeding with Russian horses, put the breed at risk. In 1935, a group of Türkmen rode 300 miles to Moscow in a bid to protect the breed. By 1973, only 18 pure bred Akhal-Teke horses remained. Independence restored the right to own horses and encouraged promotion of the Akhal-Teke breed. The state seal, created in 1992, bears the image of the Akhal-Teke, as does the currency, and April 27 was declared the annual holiday of the Türkmen horse.

Architecture

People live in one-story homes with walled courtyards, or Soviet-era apartment high-rises. The traditional dwelling is a felt tent called a "black house" (gara oÿ) like the yurts used by nomads through the region. The frame may be dismantled so that the tent can be packed up for travel. Some homes have furniture, and some do not. Padded mats, the traditional bedding style, may be folded away allowing sleeping space to be used during the day. Cooking is done in a separate space, usually by women, although men do outdoors spit roasts. Most Türkmen eat sitting on the floor around a large cloth. The toilet is separate. Living spaces are kept clean, shoes are never worn in the house, and the dwelling is covered with carpets.

Art

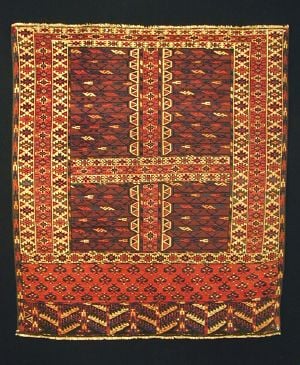

The five traditional carpet designs that form motifs in the country's state emblem and flag represent the main five tribes—Teke, Yomut, Arsary, Chowdur, and Saryk. The yomut is a type of carpet hand-woven by Yomut tribe members.

Food

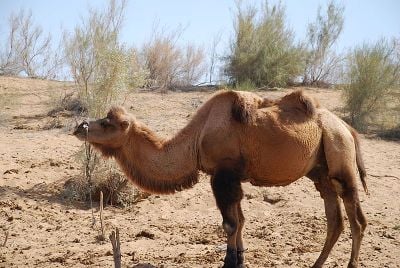

Turkmen are meat eaters. Meat from sheep, cattle, camels, goats, chicken, and pig is boiled or fried inside a casing of dough. Soup is served with meat or noodles, and may serve as breakfast. Every meal includes bread, either cheap Russian-style loaves or traditional flatbread that is made at home in a traditional Central Asian dome-shaped clay oven placed outside the home. Hot green tea accompanies most meals, drunk from shallow bowl-like cups. Türkmen also drink black tea, seltzer water, imported sodas, wine, beer, and liquor. Fruit, vegetables, nuts, and grains are bought at the bazaar. State stores sell butter, bottled water, milk, and sausages.

Clothing

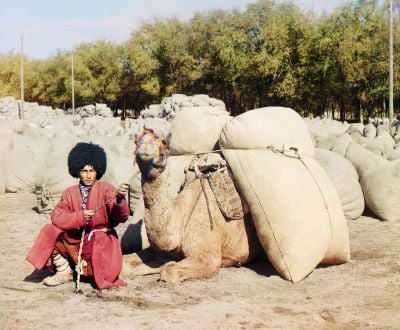

Men wear Western-style pants and jackets, as well as the distinctive traditional telpek large black sheepskin hats that resemble "afro" hairstyles. On special occasions, white telpeks are worn with dark, baggy pants tucked into high black boots. Traditional clothing includes baggy pants, knee-length boots and a cotton overcoat. Traditional clothing for women includes long, flowing solid-colored dresses in bright tones decorated with elaborate embroidery around the collar. Some women continue the tradition of wearing a head scarf in the first year of marriage. Adult women wear their hair long and upswept, and in long braids for girls. Silver jewelry and pierced ears are common.

Literature

Folk literature includes the epic poems (dastans) Gorgut Ata and Göroglu, which show early Turkic culture with Islamic values added. Turkmen oral tradition is based on the dastan, which is a combination epic tale and lyric poem, sung by an itinerant bakshy who sing either unaccompanied or with instruments such as the two-stringed lute called dutar. After independence, efforts were made to revive the dastan tradition, to promote Türkmen identity and unity.

Literary figures include the poets Mammetveli Kemine (1770–1840) and Mollanepes (1810–1862), as well as eighteenth century poet Magtymguly Pyragy, who is considered the Türkmen national poet, who wrote four line qoshunk lyrics. His poems called for the fragmented Türkmen tribes to unite, and later governments promoted Magtymguly’s work to foster nationalism.

Music

The music of the nomadic and rural Turkmen people is closely related to Kyrgyz and Kazakh folk forms. The Central Asian classical music tradition mugam is present in Turkmenistan where it is called mukamlar. It is performed by a dutarist and gidjakist, or by an ensemble of dutarists. The dutar is the most representative instrument of Turkmen folk music. It is used in many styles, ranging from the mukamlar and saltiklar to the kirklar and navoi. These are performed by professional musicians called sozanda. Bakshy were formerly the most important musicians in Turkmen society, along with tuidukists. They played the dutar to celebrate weddings, births, and other events. New music combines pop and traditional Türkmen music called estrada.

As a republic of the Soviet Union, Turkmenistan's national anthem was Turkmenistan, composed by Veli Mukhatov with words by Aman Kekilov. In 1997 (well after independence), the anthem was changed to Independent, Neutral, Turkmenistan State Anthem, the music and lyrics of which were written by President-for-Life Saparmurat Niyazov.

Performing arts

The government promotes traditional dancing. Troupes of female dancers act as cultural ambassadors. Soviet rule brought theaters, television, radio, and cinemas imparting Soviet values. Satellite television dishes have become popular in the cities, bringing broadcasts of Indian music videos, Mexican and American soap operas, as well as American pop music.

Sports

Horse riding and falconry are traditional sports in Turkmenistan. There is a National Falconers Club of Turkmenistan. Football is a popular team game.

Notes

- ↑ О Туркменистане Туркменистан — одна из пяти стран Центральной Азии, вторая среди них по площади (491,21 тысяч км2), расположен в юго-западной части региона в зоне пустынь, севернее хребта Копетдаг Туркмено-Хорасанской горной системы, между Каспийским морем на западе и рекой Амударья на востоке. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ↑ CIA, Turkmenistan World Factbook. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Turkmenistan International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ CIA, Turkmenistan World Factbook. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blackwell, Carole. Tradition and Society in Turkmenistan: Gender, oral culture and song. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2001. ISBN 0700713549

- Broughton, Simon, and Mark Ellingham (eds.). World Music, Vol. 2: Latin & North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific. Rough Guides, 2000. ISBN 1858286360

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn. Tribal Nation: Ghe making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 0691117756

- Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game: The struggle for empire in central Asia. New York: Kodansha International, 1992. ISBN 4770017030

- Irons, William. The Yomut Turkmen: A study of social organization among a central Asian Turkic-speaking population. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1975. ISBN 978-1949098037

- Rall, Ted. Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the new Middle East? New York: NBM, 2006. ISBN 1561634549

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Turkmenistan Countries and Their Cultures

- Turkmenistan CIA World Factbook

- Turkmenistan country profile BBC

- Turkmenistan Encyclopedia of the Nations

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Turkmenistan history

- Geography_of_Turkmenistan history

- History_of_Turkmenistan history

- Turkmen_language history

- Politics_of_Turkmenistan history

- Economy_of_Turkmenistan history

- Demographics_of_Turkmenistan history

- Human_rights_in_Turkmenistan history

- Saparmurat_Niyazov history

- Göktürks history

- Akhal-Teke history

- Music_of_Turkmenistan history

- Culture_of_Turkmenistan history

- Turkmen_people history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/400px-Presidential_Palace%2C_Ashgabat%2C_(5730564029).jpg)