Vocational education (or Vocational Education and Training (VET), also called Career and Technical Education (CTE) prepares learners for careers in manual or practical activities, traditionally non-academic and only related to a specific trade, occupation, or "vocation." Vocational education might be contrasted with education in a usually broader scientific field, which might concentrate on theory and abstract conceptual knowledge, characteristic of tertiary education.

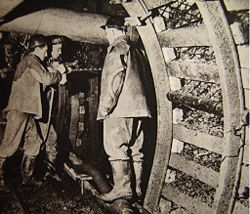

In the past, such education was in the form of apprenticeships, in which young people learned from the master the skills necessary for particular trades. Thus, it was associated with the lower social classes as compared to the classical education that was received by gentlemen. Following the industrialization of the nineteenth century, however, vocational education began to be introduced into the school educational system.

Vocational education has diversified over the twentieth century and now exists in industries as wide-ranging as retail, tourism, information technology, funeral services, and cosmetics, as well as in the traditional crafts and cottage industries. It thus forms an integral part of the educational system as a whole, providing training for a large proportion of members of modern society, complementing and supporting the more academic, scholarly educational programs offered in traditional liberal arts colleges and research universities.

History

The idea of vocational education can be traced to apprenticeships. Blacksmiths, carpenters, merchants, and other trades have existed almost since the advent of civilization, and there has always been apprenticeship-style relationships where specific techniques and trades have been passed down to members of the younger generation.[1]

Vocational education as we understand it today started in the early twentieth century. The industrialized countries of the West were the first to notice the benefits of having a specialized skilled work force and diverted funds to institutions that taught such skills. For most of the twentieth century, vocational education focused on specific trades such as an automobile mechanic or welder, and was therefore associated with the activities of lower social classes. As a consequence, it attracted a level of stigma, and is often looked upon as being of inferior quality to standard post-secondary education. However, as the labor market became more specialized and economies demanded higher levels of skill, governments and businesses increasingly invested in vocational education through publicly funded training organizations and subsidized apprenticeship or traineeship initiatives.

Towards the end of the twentieth century a new trend helped further the appreciation of vocational education. Up until that time, most vocational education had taken place at vocational or technology schools. However, community colleges soon started to offer vocational education courses granting certificates and associate degrees in specialized fields, usually at a lower cost and with comparable, if not better, curricula.[2]

Philosophy

The general philosophy of vocational education stands in stark contrast to the ideology of a liberal arts education. While a liberal arts style education strives to give students a broad range of cross-disciplinary knowledge and at the same time a single focus (the student's choice of major), vocational education operates under the theory that only information pertinent to a specific trade is necessary for a person to enter the work force. Within the trade that is chosen, a student of a vocational program may learn less theory than his or her counterpart at a liberal arts school, but will probably obtain more direct experience and be well suited to enter the workforce upon graduation. A vocational student will learn how to use the most up to date technology in the field he or she has chosen, will be taught about that industry's trends, the skills required to work in the field, possible places of employment, and will be ready to take any certification or registering tests that are required by local and/or regional governments.[1]

Programs offered at the secondary education level operate under the philosophy that such programs act as a supplement to students who may not necessarily have the skills required to go to a traditional post-secondary education or for students at high-risk, due to personal, economic, and social situations. While a social stigma may be attached to such programs, these curricula are often looked at as alternatives, aimed at giving those with different learning styles and interests a chance to earn an education that can be just as beneficial as a non-vocational one.[1]

Vocational education internationally

Vocational education programs can be found in countries throughout the world. Several examples follow.

Australia

In Australia vocational education and training is mostly post-secondary and provided through the Vocational Education and Training (VET) system and by Registered Training Organisations. This system encompasses both government and private providers in a nationally recognized quality system based on agreed and consistent assessment standards.

The National Centre for Vocational Education Research, or NCVER, is a not-for-profit company owned by the federal, state, and territory ministers responsible for training. It is responsible for collecting, managing, analyzing, evaluating and communicating research and statistics about vocational education and training (VET).[3]

Finland

Finland has two kinds of vocational education, secondary and post-secondary. Secondary education at a vocational school (ammattikoulu) is usually taken immediately after primary school, at ages of 16-21. Some programs, however, require a secondary academic degree (ylioppilastutkinto, or matriculation examination). The education is primarily vocational, and little academic education is given.

Higher vocational schools (ammattikorkeakoulu, or AMK) award post-secondary degrees based on three to five years of study. Legally, AMK degrees are not university degrees in Finland, although in foreign countries similar degrees may be called "university level." This is reflected by some Finnish schools giving English titles such as Bachelor of Science, with no Finnish translation.

German speaking countries

Vocational education is an important part of the education systems in Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland (including the French speaking part of the country).

For example, in Germany a law (the Berufsausbildungsgesetz) was passed in 1969 which regulated and unified the vocational training system and codified the shared responsibility of the state, the unions, associations, and chambers of trade and industry. The system is very popular in modern Germany: in 2001, two-thirds of young people aged under 22 began an apprenticeship, and 78 percent of them completed it, meaning that approximately 51 percent of all young people under 22 have completed an apprenticeship. One in three companies offered apprenticeships in 2003; in 2004 the government signed a pledge with industrial unions that all companies except very small ones must take on apprentices.[4]

The vocational education systems in the other German speaking countries are very similar to the German system and a vocational qualification from one country is generally also recognized in the other states within this area.

Additionally, there is the Fachhochschule (FH) since the 1970s in West Germany and since the 1990s in Austria, former East Germany, Liechtenstein, and in Switzerland. Historically, Fachhochschulen were meant as a way of academic qualification for people who went through an apprenticeship, especially in technical professions. This is called Zweiter Bildungsweg (rough literal translation: second educational path), an alternative to the classical academic career path from Gymnasium (school) to a university. However, nowadays Fachhochschule have become a fixture in German higher education and a considerable percentage of the FH students do not have an apprenticeship, but rather enter the FH straight after secondary school. Until recently, Fachhochschulen only offered Diplom (FH) degrees (such as a diploma in engineering or social work) in programs which stretched over seven or eight semesters, and typically include one semester or so of industrial internship. More recently, many Fachhochschulen switched to a system where they offer Bachelor's and Master's degrees.[5]

India

Vocational training in India is provided on a full time as well as part time basis. Full time programs are generally offered through industrial training institutes. Part time programs are offered through state technical education boards or universities who also offer full-time courses. Vocational training has been successful in India only in industrial training institutes and that too in engineering trades. There are many private institutes in India which offer courses in vocational training and finishing, but most of them have not been recognized by the Government of India. India is a pioneer in vocational training in Film & Television, and Information Technology.[6]

New Zealand

New Zealand is served by 41 Industry Training Organsiations (ITO). The unique element is that ITOs purchase training as well as set standards and aggregate industry opinion about skills in the labor market. Industry Training, as organized by ITOs, has expanded from apprenticeships to a more true life long learning situation with, for example, over ten percent of trainees are aged 50 or over. Moreover much of the training is generic. This challenges the prevailing idea of vocational education and the standard layperson view that it focuses on apprenticeships.[7] Polytechnics, Private Training Establishments, Wananga, and others also deliver vocational training, amongst other areas.

United Kingdom

Apprenticeships have a long tradition in the United Kingdom's education system. In early modern England "parish" apprenticeships under the Poor Law came to be used as a way of providing for poor children of both genders alongside the regular system of apprenticeships, which tended to provide for boys from slightly more affluent backgrounds.

In modern times, the system became less and less important, especially as employment in heavy industry and artisan trades declined. Traditional apprenticeships reached their lowest point in the 1970s: by that time, training programs were rare and people who were apprentices learned mainly by example. In 1986, National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) were introduced, in an attempt to revitalize vocational training.

In 1994, the government introduced Modern Apprenticeships (in England, but not Scotland or Wales, the name was changed to Apprenticeships in 2004), again to try to improve the image of work-based learning and to encourage young people and employers to participate. These apprenticeships are based on "frameworks" that consist of National Vocational Qualifications, a technical certificate, and key skills such as literacy and numeracy.

Recognizing that many young people, parents, and employers still associated apprenticeship and vocational education with craft trades and manual occupations, the government developed a major marketing campaign in 2004.[8] Vocational training opportunities now extend beyond "craft" and skilled trades to areas of the service sector with no apprenticeship tradition. Providers are usually private training companies but might also be further education colleges, voluntary sector organizations, Chambers of Commerce, or employer Group Training Associations. There is no minimum time requirement for completion of a program, although the average time spent completing a framework is roughly twenty-one months.

United States

In the United States, the approach varies from state to state. Most of the technical and vocational courses are offered by community colleges, though several states have their own institutes of technology which are on an equal accreditational footing with other state universities.

Historically, junior high schools and high schools have offered vocational courses such as home economics, wood and metal shop, typing, business courses, drafting, and auto repair, though schools have put more emphasis on academics for all students because of standards based education reform. School to Work is a series of federal and state initiatives to link academics to work, sometimes including spending time during the day on a job site without pay.

Federal involvement is principally carried out through the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act. Accountability requirements tied to the receipt of federal funds under this Act provide some overall leadership. The Office of Vocational and Adult Education within the US Department of Education also supervises activities funded by the Act.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Encyclopedia of Education, 2002, "History of Vocational and Technical Education" The Gale Group, Inc. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ↑ C. W. Brodhead, "Image 2000: A Vision for Vocational Education," Vocational Education Journal 66, no. 1 (January 1991): 22-25.

- ↑ NCVER.com, 2007, "About NCVER: What We Do" Retrieved October 17, 2007

- ↑ Dagmar Kraemer, The Dual System of Vocational Training in Germany, BASIS-INFO 11-1995, Social Policy.

- ↑ University of Applied Sciences, 2007, Fachhochschule Bielefeld Retrieved October 19, 2007

- ↑ Education in India, 2007, Vocational Education in India Retrieved October 19, 2007

- ↑ Industry Training Federation, New Zealand, 2007, "About Us" Retrieved October 19, 2007

- ↑ Department for Education and Skills, 2005, Blueprint for Apprenticeships.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Achilles, C. M., M.N. Lintz, and W.W. Wayson. 1989. "Observations on Building Public Confidence in Education." Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11 no. 3, 1989: 275-284.

- Banach, William J. 1996. The ABC Complete Book of School Marketing. Banach, Banach & Cassidy.

- Brodhead, C. W. "Image 2000: A Vision for Vocational Education." Vocational Education Journal 66, no. 1, January 1991: 22-25.

- Buzzell, C.H. "Let Our Image Reflect Our Pride." Vocational Education Journal 62, no. 8, November-December 1987: 10.

- Clarke, Linda. 2007. Vocational Education: International Perspectives and Development. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415380614

- Felder, Henry and Sarah L. Glavin. 1995. Vocational Education: Changes at High School Level After Amendments to Perkins Act. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0788141041

- O'Connor, P.J., and S.T. Trussell. "The Marketing of Vocational Education." Vocational Education Journal 62, no. 8, November-December 1987: 31-32.

- Ries, E. "To 'V' or Not to 'V': for Many the Word 'Vocational' Doesn't Work." Techniques 72, no. 8 (November-December 1997): 32-36.

- Ries, A., and J. Trout. 1994. The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing. Profile Business. ISBN 978-1861976109

- Sharpe, D. "Image Control: Teachers and Staff Have the Power to Shape Positive Thinking." Vocational Education Journal 68, no. 1, January 1993: 26-27.

- Shields, C.J. "How to Market Vocational Education." Curriculum Review, November 1989: 3-5

- Silberman, H.F. "Improving the Status of High School Vocational Education." Educational Horizons 65, no. 1, Fall 1986: 5-9.

- Tuttle, F.T. "Let's Get Serious about Image-Building." Vocational Education Journal 62, no. 8, November-December 1987: 11.

- "What Do People Think of Us?" Techniques 72, no. 6, September 1997: 14-15.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

Vocational School Examples

- Automotive Vocational Schools, a website devoted to vocational schools in the automotive field.

- Jschool: Journalism Education & Training, an example of a vocational college in journalism education.

- Medical Vocational Schools, a website devoted to vocational schools in the medical field.

- Agricultural Vocational Schools, website for the TeachAManToFish network of agricultural vocational schools.

National and International organizations and agencies

- European Forum of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (EFVET)

- UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training

- US Dept of Education - Office of Vocational and Adult Education

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.