Watercolor painting

Watercolor painting is a painting method. A watercolor is either the medium or the resulting artwork. Watercolor, also known in French as aquarelle, is named for its primary component. It consists of a pigment dissolved in water and bound by a colloid agent (usually a gum, such as gum arabic); it is applied with a brush onto a supporting surface, such as vellum, fabric, or—more typically—dampened paper. The resulting mark (after the water has evaporated) is transparent, allowing light to reflect from the supporting surface, to luminous effect. Watercolor is often combined with gouache (or "bodycolor"), an opaque water-based paint containing a white element derived from chalk, lead, or zinc oxide.[1]

The technique of water-based painting dates to ancient times, and belongs to the history of many cultures in the world. In the West, European artists used watercolor to decorate illuminated manuscripts and to color maps in the Middle Ages, and to make studies from nature and portrait miniatures during the Renaissance.[2] When the Western world began to mass produce paper, the medium took on a whole new dimension of creativity.

The advantages of watercolor lie in the ease and quickness of its application, in the transparent effects achievable, in the brilliance of its colors, and in its relative cheapness.

History

Watercolor is a tradition that dates back to primitive man using pigments mixed with water to create cave paintings by applying the paint with fingers, sticks and bones. Ancient Egyptians used water-based paints to decorate the walls of temples and tombs and created some of the first works on paper, made of papyrus. But it was in the Far East and Middle East that the first watercolor schools or predominant styles emerged in the modern sense.

Chinese and Japanese masters painted on silk as well as exquisite handmade paper. Their art was filled with literary allusion and calligraphy, but the primary image was typically a contemplative landscape. This characteristic anticipated what was to be a central aspect of Western watercolor traditions in later centuries. In India and Persia, the opaque gouache paintings created by the Moslems depicted religious incidents derived from Byzantine art.[3]

During the Middle Ages, monks of Europe used tempera to create illuminated manuscripts. These books were considered a major form of art, equivalent to easel painting in later years. The most famous illuminated book was by the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Herman, and Jean. This calendar, Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, or sometimes called "The Book of Hours," was created about 1415. Medieval artists also worked in fresco which continued throughout the Renaissance. Fresco is a method by which pigments are mixed with water and applied to wet plaster. This method was used primarily to create large wall paintings and murals by such artists as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. The most famous fresco is Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, painted from 1508 to 1512.[4]

Paper played an important role in the development of watercolor. China has been manufacturing paper since ancient times. The Arabs learned their secrets during the eighth century. Paper was imported to Europe until the first papermaking mills were finally established in Italy in 1276. A few other mills developed later in other parts of Europe, while England developed its first mills by 1495. However, high-quality paper was not produced in Britain until much later, during the eighteenth century.[5]

During and after the Renaissance, artists like Albrecht Durer, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and Sir Anthony van Dyck used watercolors to tint and shade drawings and woodcuts. In Germany, Dürer's (1471-1528) watercolors led to the establishment of a school of watercolor painting that was led by Hans Bol (1534-1593).[6] Durer is traditionally considered the first master of watercolor because his works were full renderings used as preliminary studies for other works.

Since paper was considered a luxury item in these early ages, traditional Western watercolor painting was slow in evolving. The increased availability of paper by the fourteenth century finally allowed for the possibility of drawing as an artistic activity.

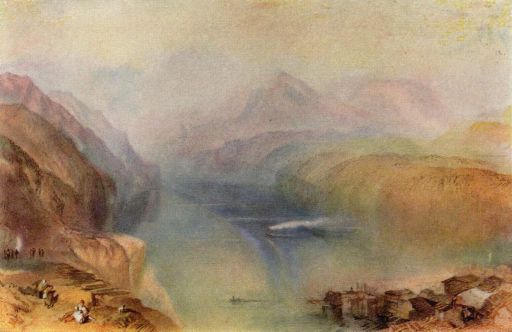

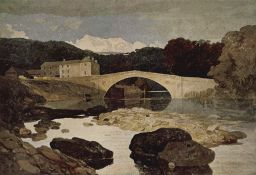

From the seventeenth century to the present, the British school of watercolor, which especially features landscape subjects, has been perhaps the most continuous and widely followed tradition in Europe. Among the most famous of the artists are: Alexander Cozens, William Gilpin, Thomas Gainsborough, Francis Towne, Paul Sandby, Thomas Girtin, John Sell Cotman, Samuel Palmer, William Blake, John Constable, J. M. W. Turner, and Richard Parkes Bonnington.

Famous watercolorists

The three English artists credited with establishing watercolor as an independent, mature painting medium are Paul Sandby (1730-1809), Thomas Girtin (1775-1802), who pioneered watercolor's use in large format landscape painting, and J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851). Turner created hundreds of historical, topographical, architectural, and mythological paintings. His method of developing the watercolor painting in stages, starting with large, vague color areas established on wet paper, then refining the image through a sequence of washes and glazes, permitted him to produce large numbers of paintings with workshop efficiency and made him a multimillionaire in part through sales from his personal art gallery, the first of its kind. Among the important and highly talented contemporaries of Turner and Girtin were John Varley, John Sell Cotman, Anthony Copley Fielding, Samuel Palmer, William Havell, and Samuel Prout. The Swiss painter Louis Ducros was also widely known for his large format, romantic paintings in watercolor.

The American West was an important area in the history of American art, and of watercolor in particular. Much of the record of exploration of the lands and people west of the Mississippi was kept by artists whose only means of painting was watercolor. George Catlin (1796-1870) was one of the "explorer artists" who used watercolor to document his travels among Indian tribes during the 1830s. Thomas Moran's watercolor sketches of Yellowstone, in 1871, so impressed Congress that they voted to make Yellowstone the nation's first National Park. The American Society of Painters in Watercolor (now the American Watercolor Society) was founded in 1866.[7]

Major nineteenth century American exponents of the medium included William Trost Richards, Fidelia Bridges, Thomas Moran, Thomas Eakins, Henry Roderick Newman, John LaFarge, and, preeminently, Winslow Homer. Watercolor was less popular in continental Europe, though many fine examples were produced by French painters, including Eugene Delacroix, Francois-Marius Granet, Henri-Joseph Harpignies, and the satirist Honore Daumier.

Among the many twentieth century artists who produced important works in watercolor were Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, Egon Schiele, and Raoul Dufy; in America the major exponents included Charles Burchfield, Edward Hopper, Charles Demuth, Elliot O'Hara, and, above all, John Marin, 80 percent of whose total output is in watercolor. In this period, American watercolor (and oil) painting was often imitative of European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but significant individualism flourished within "regional" styles of watercolor painting in the 1920s to 1940s, in particular the "Ohio School" of painters centered around the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the "California Scene" painters, many of them associated with Hollywood animation studios or the Chouinard School of Art (now CalArts Academy).

During the 1940s, artistic experimentation became a major focus in the New York City art scene resulting in the development of Abstract Expressionism. Watercolor began to lose a certain amount of its popularity. It was not a medium which played a role in the evolution of the new movement in abstraction. Watercolors were small and intimate in scale and were subordinate to the huge canvases of the Abstract Expressionists.

However, one such artist, Mark Rothko (1903-1970), utilized large areas of transparent washes and color staining on his canvases to create large scale works which were atmospheric, contemplative, and reminiscent of the watercolor tradition. Later, a second generation of Abstract Expressionist, including Sam Francis (1923-1994) and Paul Jenkins (b. 1923), also employed similar wash methods to produce transparent color fields on large canvases. By incorporating watercolor techniques into canvas painting, American artists not only re-popularized the medium but continued a long tradition of innovative experimentation.[8]

Watercolors continue to be utilized by important artists such as Joseph Raffael, Andrew Wyeth, Philip Pearlstein, Eric Fischl, Gerard Richter, and Francesco Clemente. Modern watercolor paints are now as durable and colorful as oil or acrylic paints, and the recent renewed interest in drawing and multimedia art has also stimulated demand for fine works in watercolor.

- Watercolors

Albrecht Durer's Tal von Kalchreuth (1494-1495)

J.M.W. Turner's Ein Bett:Faltenwurfstudie

Winslow Homer'sAfter the Hurricane (1899)

Materials

Paint

Commercial watercolor paints come in two grades: "Artist" (or "Professional") and "Student." Artist quality paints are usually formulated using a single pigment, which results in richer color and vibrant mixes. Student grade paints have less pigment, and often are formulated using two or more less expensive pigments. Artist and Professional paints are more expensive but many consider the quality worth the higher cost.

Paints comprise four principal ingredients:

- Colorant, commonly pigment (an insoluble inorganic compound or metal oxide crystal, or an organic dye fused to an insoluble metal oxide crystal)

- Binder, the substance that holds the pigment in suspension and fixes the pigment to the painting surface

- Additives, substances that alter the viscosity, hiding, durability or color of the pigment and vehicle mixture

- Solvent, the substance used to thin or dilute the paint for application and that evaporates when the paint hardens or dries

Thanks to modern industrial organic chemistry, the variety, saturation (brilliance), and permanence of artists' colors available today is greater than ever before.

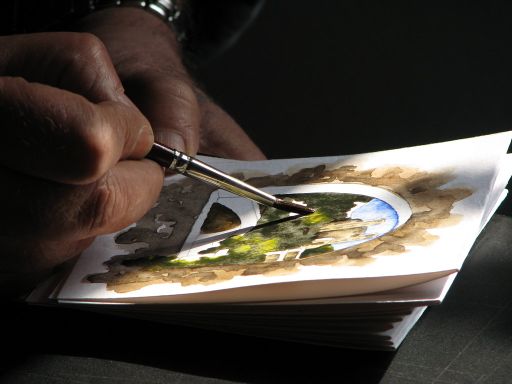

Brushes

A brush consists of three parts: The tuft, the ferrule and the handle. The tuft is a bundle of animal hairs or synthetic fibers tied tightly together at the base; the ferrule is a metal sleeve that surrounds the tuft, gives the tuft its cross sectional shape, provides mechanical support under pressure, and protects from water the glue joint between the trimmed, flat base of the tuft and the lacquered wood handle, which is typically shorter in a watercolor brush than in an oil painting brush, and also has a distinct shape—widest just behind the ferrule and tapering to the tip.

Every watercolor painter works in specific genres and has a personal painting style and "tool discipline," and these largely determine his or her preference for brushes.

Paper

Most watercolor painters before 1800 had to use whatever paper was at hand: Thomas Gainsborough was delighted to buy some paper used to print a Bath tourist guide, and the young David Cox preferred the heavy paper used to wrap packages. James Whatman first offered a wove watercolor paper in 1788, and the first machinemade ("cartridge") papers from a steam powered mill in 1805.

All art papers can be described by eight attributes: Furnish, color, weight, finish, sizing, dimensions, permanence, and packaging. Watercolor painters typically paint on paper specifically formulated for watermedia applications. Fine watermedia papers are manufactured under the brand names Arches, Fabriano, Hahnemuehle, Lanaquarelle, Saunders Waterford, Strathmore, Winsor & Newton, and Zerkall; and there has been a recent remarkable resurgence in handmade papers, notably those by Twinrocker, Velke Losiny, Ruscombe Mill, and St. Armand.

Techniques

Watercolor painting has the reputation of being quite demanding; it is more accurate to say that watercolor techniques are unique to watercolor. Unlike oil or acrylic painting, where the paints essentially stay where they are put and dry more or less in the form they are applied, water is an active and complex partner in the watercolor painting process, changing both the absorbency and shape of the paper when it is wet and the outlines and appearance of the paint as it dries. The difficulty in watercolor painting is almost entirely in learning how to anticipate and leverage the behavior of water, rather than attempting to control or dominate it.

Washes and glazes

Basic watercolor technique includes washes and glazes. In watercolors, a wash is the application of diluted paint in a manner that disguises or effaces individual brush strokes to produce a unified area of color. Typically, this might be a light blue wash for the sky.

A glaze is the application of one paint color over a previous paint layer, with the new paint layer at a dilution sufficient to allow the first color to show through. Glazes are used to mix two or more colors, to adjust a color (darken it or change its hue or chroma), or to produce an extremely homogeneous, smooth color surface or a controlled but delicate color transition (light to dark, or one hue to another). This method is currently very popular for painting high contrast, intricate subjects, in particular colorful blossoms in crystal vases brightly illuminated by direct sunlight.

Wet in wet

Wet in wet includes any application of paint or water to an area of the painting that is already wet with either paint or water. In general, wet in wet is one of the most distinctive features of watercolor painting and the technique that produces the most striking painterly effects.

Drybrush

At the other extreme from wet in wet techniques, drybrush is the watercolor painting technique for precision and control, supremely exemplified in many botanical paintings and in the drybrush watercolors of Andrew Wyeth. The goal is to build up or mix the paint colors with short precise touches that blend to avoid the appearance of pointilism. The cumulative effect is objective, textural, and highly controlled, with the strongest possible value contrasts in the medium.

Notes

- ↑ Metmuseum.org, Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Big City Art, Watercolor History. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Answers.com, Watercolor painting.

- ↑ Collectorsguide.com, What is Watercolor? Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Big City Art, Brief History of Watercolor Painting. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brandt, Rex. The Winning Ways of Watercolor: Basic Techniques and Methods of Transparent Watercolor in Twenty Lessons. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1973. ISBN 0-442-21404-9

- Clarke, Michael. The Tempting Prospect: A Social History of English Watercolors. British Museum Publications, 1981.

- Dewey, David. The Watercolor Book: Materials and Techniques for Today's Artist. Watson-Guptill, 1995. ISBN 0-8230-5641-4

- Finch, Christopher. Nineteenth-Century Watercolors. Abbeville Press, 1991. ISBN 1558590196

- Finch, Christopher. American Watercolors. Abbeville Press, 1991.

- Finch, Christopher. Twentieth-Century Watercolors. Abbeville Press, 1988. ISBN 089659811X

- Hardie, Martin. Water-Colour Painting in Britain. Chrysalis Books, 1988 (original 1966-1968). ISBN 0713406992

- LeClair, Charles. The Art of Watercolor. Watson-Guptill, 1999. ISBN 0-8230-0292-6

- Lyles, Anne & Robin Hamlyn. British Watercolours from the Oppé Collection. Tate Gallery Publishing, 1997. ISBN 1-85437-240-8

- Royal Watercolour Society. The Watercolour Expert. Cassell Illustrated, 2007 (original 2004). ISBN 1844031497

- Ruskin, John. The Elements of Drawing [1857]. Watson-Guptill, 1997. ISBN 0-8230-1602-1

- Seymour, Pip. Watercolour Painting: A Handbook for Artists. Lee Press, 1997. ISBN 0-9524727-4-0

- Shanes, Eric. The Great Watercolours. Royal Academy of Arts, 2000. ISBN 0-8109-6634-4

- Sideway, Ian. The Watercolor Artist's Paper Directory. North Light, 2000. ISBN 1581800347

- Smith, Stan. Watercolor: The Complete Course. Reader's Digest, 2000 (original 1995). ISBN 0-89577-653-7

- Turner, Jacques. Brushes: A Handbook for Artists and Artisans. Design Press, 1992. ISBN 0830639756

- Turner, Sylvie. The Book of Fine Paper. Thames & Hudson, 1998. ISBN 0500018715

- Wilton, Andrew & Anne Lyles. The Great Age of British Watercolours (1750-1880). Prestel, 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1254-5

- Whitney, Edgar A. Complete Guide to Watercolor Painting. Watson-Guptill, 2001 (original 1974). ISBN 0-486-41742-5

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Brief History of Watercolor painting Bigcityart.com.

- "Guide to Watercolor Painting". Handprint.com.

- Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850 Metmuseum.org.

- Learning Center Watercolorpainting.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.