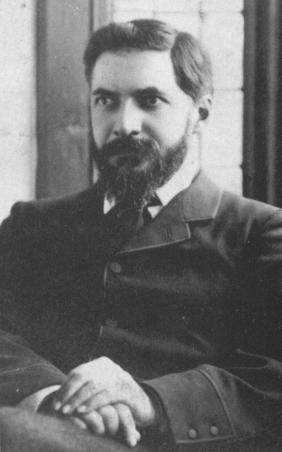

William Matthew Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (June 3, 1853 – July 28, 1942), commonly known as Flinders Petrie, was an English Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology. His work allowed precise measurement and dating of ancient monuments. His particular interest was in Ancient Egypt, beginning with the Great Pyramid of Giza, and excavating numerous sites of Greek origin from the Mycenaean civilization. Among his significant discoveries was the stele of Merneptah, which contains the earliest known reference to Israel.

Flinders Petrie was fascinated by the Holy Land, visiting Palestine on several occasions, and living the last years of his life in Jerusalem. He was knighted for his contributions to archaeology, advancing scientific knowledge of the part of the world that holds great spiritual significance to humankind.

Life

William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born on June 3, 1853 in Charlton, England, in a family of devoted Christians. He was the grandson of the explorer, Captain Matthew Flinders, who was the first man to chart Australia. His mother, Anne, was also interested in science, collecting fossils and minerals. She encouraged the intellectual pursuits of her son, teaching him at home, and introducing him to the Hebrew, Latin, and Greek languages.

On the other hand, his father William, a civil engineer and professional surveyor, taught his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for a career excavating and surveying ancient sites in Egypt and the Levant. Already as a teenager Petrie started to survey buildings and historical places across England, including the famous Stonehenge. In 1880 he published this work in Stonehenge: Plans, Description, and Theories. At that time he was working as a practical surveyor in south England. His only formal education was a university course in mathematics.

Under the influence of the theories of Piazzi Smyth, Petrie and his father went to Egypt in 1880 to survey the pyramids. William Petrie saw in Smyth's theories an admirable reconciliation of science and religion, and decided that he and his son should use their skills to secure more precise measurements of the Great Pyramid. However, Flinders Petrie's measurements proved that Smyth's theories were based on a logical fallacy. Nevertheless, he himself had become hooked on Egyptology.

Having accomplished such impressive work at Giza, Petrie was recommended to the Egypt Exploration Fund (later the Egypt Exploration Society), who needed an archaeologist in Egypt to succeed Édouard Naville. Petrie accepted the position and was given the sum of £250 per month to cover the excavations’ expenses.

In November 1884, Petrie arrived in Egypt and continued his excavations. His meticulous and systematic style of research soon made him famous. Petrie went on to excavate many of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt such as Abydos and Amarna. He also made a very significant discovery, that of the stele of Merneptah. At the same time he occasionally traveled to Middle East, where he performed several field studies in Palestine.

Although Petrie had no formal education, he was made a professor at the University College, London. There he served from 1892 to 1933 as the first Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology. This chair had been funded by Amelia Edwards, a strong supporter of Petrie. He continued to excavate in Egypt after taking up the professorship, training many of the best archaeologists of the day. In 1913 Petrie sold his large collection of Egyptian antiquities to University College, London, where it is housed in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. The year 1923 saw Petrie knighted for services to British archaeology and Egyptology.

In 1926 the focus of Petrie’s work shifted permanently to Palestine and he began excavating several important sites in the southwestern region of the country, including Tell el-Jemmeh and Tell el-Ajjul. Petrie spent the last years of his life living in Jerusalem, where he died in 1942. During this period, he lived with Lady Petrie at the British School of Archaeology, and then temporarily headquartered at the American School of Oriental Research (later the Albright Institute).

Petrie arranged that, on his death, his head be donated to science, specifically the Royal College of Surgeons of London, so that it could be studied for its high intellectual capacity. Petrie was, no doubt, influenced by his interest in eugenics. However, due to the wartime conditions that existed in 1942, his severed head was delayed in transport from Jerusalem to London, and was eventually lost. Petrie’s body, minus its head, was interred in the Protestant Cemetery on Mt. Zion.

Work

Petrie can be considered the founder of systematic research methods in archaeology. His work Inductive Metrology: Recovery of Ancient Measures from the Monuments, which he wrote in his early twenties, described an innovative and precise method of determining the units of measurement used in constructing ancient monuments. His painstaking recording and study of artifacts set new standards in the field. By linking styles of pottery with time periods, he was the first to use seriation, a new method for establishing the chronology of a site. A number of Petrie's discoveries were presented to the Royal Archaeological Society and described in the society's Archaeological Journal by his good friend and fellow archaeologist, Flaxman Charles John Spurrell.

Among many his significant discoveries in Egypt is his work in the Al-Fayyum region. There, he found numerous examples of papyrus and pottery of Greek origin, which substantiated dates of ancient Mycenaean civilization. In addition, he excavated thousands of graves of ancient Egyptians at Naqadah, north of Thebes, and found the remains of the city of Akhenaton, containing many beautiful ornaments from the Amarna age (fourteenth century B.C.E.). Petrie was also involved in excavations of pit tombs in Abydos, the stelae (standing stone slabs) of which initially suggested that they belonged to pharaohs of the early Egyptian dynasties.

During his career as an Egyptologist, Petrie often made forays into Palestine, where he conducted important archaeological work. His six-week excavation of Tell el-Hesi (which was mistakenly identified as Lachish), in 1890 represents the first scientific excavation of an archaeological site in the Holy Land. At another point in the late nineteenth-century, Petrie surveyed a group of tombs in the Wadi al-Rababah (the biblical Hinnom) of Jerusalem, largely dating to the Iron Age and early Roman periods. There, in the ancient monuments, Petrie discovered two different metrical systems.

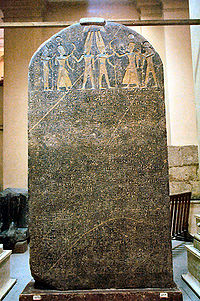

Stele of Merneptah

In Thebes, Petrie discovered a stele of Merneptah. There, he found writings that contained the earliest known Egyptian reference to Israel.

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele because of this reference to Israel, is the reverse of a stele originally erected by the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III, but later inscribed by Merneptah in the thirteenth century B.C.E. There is, in fact, only one line about Israel—"Israel is wasted, bare of seed" or "Israel lies waste, its seed no longer exists"—and very little about the region of Canaan as a whole, as Merneptah inserted just a single stanza to the Canaanite campaigns and multiple stanzas to his defeat of the Libyans.

As the stele contains only that single line about Israel, it is difficult for scholars to draw a substantial amount of information about what "Israel" meant. The stele does point out that Israel, at this stage, referred to a people, since a hieroglyphic determinative for "country" is absent regarding Israel (whereas the other areas had the determinative for "country" applied to them).

Legacy

Petrie’s most significant contribution to archaeology is his method of statistical analysis of the materials, through which he was able to rather precisely (for that time) determine how old the material was. This method began to be used again in the 1970s, with the advent of computers able to perform the calculations, replacing Petrie’s cards and calculations by hand.

In addition, Petrie improved the technique and method of field excavations, paving the way for of modern archaeology. His excavations in Palestine were the first of such a kind in the Holy Land, providing the guidelines for all future research in that area.

Major Works

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1877] 2010. Inductive Metrology: Recovery of Ancient Measures from the Monuments. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1164680628

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1880] 1990. Stonehenge: Plans, Description, and Theories. Histories & Mysteries of Man. ISBN 1854170317

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1883] 2002. The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. London: Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710307098

- Petrie, W. M. F. 1892. "The Tomb-Cutter’s Cubits at Jerusalem" in Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly 24: 24–35.

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1898] 2001. Syria and Egypt: From the Tell el Amarna Letters. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402195222

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1895] 2001. Egyptian Tales Translated from the Papyri. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402186258

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1905] 2001. A History of Egypt. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0543993264

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1906] 2001. Researches in Sinai. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402175159

- Petrie, W. M. F. & John Duncan. [1906] 2005. Hyksos and Israelite Cities. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402142293

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1907] 2005. Gizeh and Rifeh. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1421216817

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1912] 2005. The Revolutions of Civilisation. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402159315

- Petrie, W. M. F. [1932] 1969. Seventy Years in Archaeology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press Reprint. ISBN 0837122414

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Callaway, Joseph A. 1980. “Sir Flinders Petrie, Father of Palestinian Archaeology.” Biblical Archaeology Review 6 (6): 44–55.

- Dever William G. 2002. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel? Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 080282126X

- Drower, Margaret S. 1995. Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299146243

- Drower, Margaret S. 2004. Letters from the Desert: The Correspondence of Flinders and Hilda Petrie. Aris & Philips. ISBN 0856687480

- Uphill, E. P. 1972. “A Bibliography of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942).” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 31: 356–379.

External links

All links retrieved May 11, 2023.

- William Flinders Petrie, Father of Pots by Marie Parsons, TourEgypt

- Life in pictures – Photos of Petrie

- The Israel Stela

- The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology – Petrie’s Museum in London, UK

- Sir William M. Flinders Petrie, 1853-1942 The Palestine Exploration Fund

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.