Zionism

Zionism is an international political movement that originally supported the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine (Eretz-Yisra'el) and continues primarily in support for the modern state of Israel.

The term "Zionism" is derived from the word Zion (Hebrew: ציון—Tzi-yon), referring to Mount Zion, a small mountain near Jerusalem. In several biblical verses, the Israelites were called the people of Zion (Isaiah 12:6; Joel 2:23, for example). While Zionism is based in part upon the religious tradition linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, the modern Zionist movement was mainly secular, beginning largely as a response by European Jewry to antisemitism across Europe. Several types of Zionism emerged from these beginnings, including Labor Zionism, Liberal Zionism, Revisionist Zionism, and Religious Zionism.

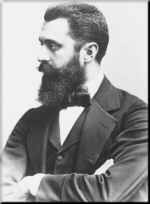

The modern Zionist movement was formally established by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl in the late nineteenth century. In response to the tragedy of European Jews during the Holocaust, Zionism became the dominant Jewish political movement after World War II. The movement eventually succeeded in establishing the state of Israel in 1948, as the world's first and only modern Jewish state.

Although some Israeli and American Jews are critical of Zionism, anyone who supports the existence of Israel as a Jewish homeland is technically defined as a Zionist. In this sense, despite widespread opposition, Zionism must be viewed as one of the most successful modern political movements.

History

| year | Jews | Non-Jews |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 6,700 | 268,000 |

| 1880 | 24,000 | 525,000 |

| 1915 | 87,500 | 590,000 |

| 1931 | 174,000 | 837,000 |

| 1947 | 630,000 | 1,310,000 |

In Jewish tradition, Eretz Israel, or Zion, is a land promised to the Jews by God, dating back to God's covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. However, although there has been a constant presence of Jews in the Land of Israel, most Jews have lived in exile since the first or second century C.E.

Jews from Babylonia, Asia Minor, and Europe are known to have immigrated to Palestine and lived in the region throughout the last millennium, though not in large numbers.[2] In the nineteenth century, a current in Judaism supporting the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the traditional Land of Israel grew in popularity.

Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest in 1882. The so-called First Aliyah (first return) saw the arrival of about 30,000 Jews over 20 years. Most immigrants came from Russia, where antisemitism was a major problem. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe. The Second Aliyah started in 1904. Further immigrations followed between the two World Wars, fueled in the 1930s by Nazi persecution.

In the 1890s, Theodor Herzl infused Zionism with a new and practical urgency. He founded the World Zionist Organization (WZO) and, together with Nathan Birnbaum, planned its first congress at Basel in 1897. This was followed a year later by a second congress held in Cologne.

The ruling power of the area, up until 1917, was the Ottoman Empire, followed by Britain on behalf of the League of Nations until after WWII. Lobbying by Chaim Weizmann and others culminated in the Balfour Declaration of 1917 by the British government. This declaration endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1922, the League of nations endorsed the declaration in the mandate it gave to Britain:

The Mandatory (Britain)… will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.[3]

However, Palestinian Arabs resisted Zionist migration. There were riots in 1920, 1921, and 1929, sometimes accompanied by massacres of Jews. Britain continued to support Jewish immigration in principle, but in reaction to Arab violence imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration to the area.

| year | Muslims | Jews | Christians | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 486,177 | 83,790 | 71,464 | 7,617 |

| 1931 | 493,147 | 174,606 | 88,907 | 10,101 |

| 1941 | 906,551 | 474,102 | 125,413 | 12,881 |

| 1946 | 1,076,783 | 608,225 | 145,063 | 15,488 |

In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws made German Jews (and later Austrian and Czech Jews) stateless refugees. Similar rules were subsequently applied by Nazi allies throughout much of Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration led to the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, which in turn led the British to establish the Peel Commission to investigate the situation. The commission called for a two-state solution and compulsory transfer of populations. This solution was rejected by the British and instead the White Paper of 1939 proposed an end to Jewish immigration by 1944, with a further 75,000 to be admitted by then. In principle, the British stuck to this policy until the end of the Mandate.

After WWII and the Holocaust, support for Zionism increased, especially among Holocaust survivors and those who sympathized with them. However, restrictions on Jewish immigration to the future Jewish homeland led to an increased sense of urgency and desperation among some Zionists. The British were attacked in Palestine by certain Zionist factions, the best known being the 1946 King David Hotel bombing. Unable to resolve the conflict, the British referred the issue to the newly created United Nations.

Zionism's victory and its aftermath

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended the partition of western Palestine into a Jewish state, an Arab state, and a UN-controlled territory around Jerusalem.[5] This partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote, which required a two-thirds majority, was a very dramatic affair and led to celebrations in the streets of Jewish cities.[6]

The Arab states, however, rejected the UN decision, demanding a single state with an Arab majority. Violence immediately exploded in Palestine between Jews and Arabs. On May 14, 1948, at the end of the British mandate, the Jewish Agency led by David Ben-Gurion declared the creation of the State of Israel. On the same day, the armies of Egypt, Transjordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia joined forces against the newly created Israel. (Yemen and Saudi Arabia sent only small contingents of soldiers and Lebanese forces did not actually enter the country.)

During the following eight months, Israel forces defended the Jewish sector and conquered portions of the Arab sector, enlarging its portion to 78 percent of British mandatory Palestine. The conflict led to the relocation of more than 700,000 Arab Palestinians,[7] of whom about 46,000 became internally displaced persons in Israel. The war ended with the 1949 Armistice Agreements, which included new cease-fire lines, the so-called Green line.

Zionism had, thus, not only succeeded in its primary goal of establish a Jewish homeland, but had proven victorious in defending the Jewish state against the combined forces of its Arab neighbors. However, despite the armistice, the Arab nations continued to reject Israel's right to exist and demanded that it retreat to the 1947 partition lines. They sustained this demand until 1967, when the rest of western Palestine was conquered by Israel during the Six-Day War, after which Arab states demanded that Israel only retreat to the 1949 cease fire line, the "borders" currently recognized by the international community. These borders are commonly referred as the "pre-1967 borders" or the "green line." The border with Egypt was legalized in the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty, and the border with Jordan in the 1994 Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace.

After the creation of the State of Israel the WZO continued to exist as an organization dedicated to assisting and encouraging Jews to migrate to Israel, as well as providing political support for Israel. The major Israeli political parties remain avowedly Zionist, although the major Israeli political parties are sharply divided on many economic, political, religious, and foreign policy issues. Some anti-Zionist Israeli groups also exist, both Jewish and Arab.

Types of Zionism

Labor Zionism

Labor Zionism became the dominant trend in the Zionist movement in the early-mid twentieth century. Labor Zionists originated in Russia. They believed that centuries of being oppressed in antisemitic societies had reduced Jews to a meek, vulnerable, despairing existence which invited further antisemitism. In their view, the best protection for Jews was to become farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own. Most Labor Zionists rejected religion as perpetuating a "diaspora mentality" among the Jewish people. After emigrating, they established rural communes in Israel called "kibbutzim," which became a mainstay of the Jewish population there in the early twentieth century.

Major theoreticians of Labor Zionism included Moses Hess, Nahum Syrkin, Ber Borochov, and Aaron David Gordon. Leading political figures in the movement included David Ben-Gurion and Berl Katznelson. Most Labor Zionists embraced Hebrew as the common Jewish tongue, rejecting Yiddish as part of the Jewish experience as second-class citizens of Europe. Because Labor Zionism was ardently secularist, the movement often had an antagonistic relationship with Orthodox Judaism.

However, Labor Zionism became the dominant force in the political and economic life of the Jews in the Land of Israel during the British Mandate of Palestine—partly as a consequence of its role in organizing Jewish economic life through the Histadrut labor movement. Labor Zionism remained the dominant ideology of the political establishment in Israel until Israel's 1977 election, when the Likud party emerged from a coalition of other Zionist factions in opposition to the Histadrut's socialist agenda.

Liberal Zionism

General Zionism (or Liberal Zionism) was the leading trend within the Zionist movement from the First Zionist Congress, in 1897, until after the First World War. Many of the General Zionists were German or Russian liberals. However, following the Bolshevik revolution and the rise of fascism, the liberals lost ground and the more militant Labor Zionists came to dominate the movement. Liberal Zionists identified with the European Jewish middle class from which many Zionist leaders, such as Herzl and Chaim Weizmann, originated. They believed that a Jewish state could be accomplished through lobbying the Great Powers of Europe and influential circles in European society. General Zionism declined in the face of growing extremism and antisemitism in Central Europe, and because of the superior ability of labor Zionism to generate migration to Palestine. The trend re-emerged in the early 1970s, in oppositions to decades of Labor dominance in Israeli politics.

Revisionist Zionism

The Revisionist Zionists were a right wing Zionist group led by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated pressing Britain to allow mass Jewish emigration and the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine. The army would force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration and promote British interests in the region. Jabotinsky was a founder and leader of the clandestine Jewish armed organization Irgun, noted for several infamous terrorist acts against the British.

Revisionist Zionism was detested by the Labor Zionist faction which accused the Revisionists as being influenced by fascism. After the 1929 Arab riots, the British banned Jabotinsky from entering Palestine. Revisionism was popular in Poland but lacked large support in Palestine. In 1935, the Revisionists left the Zionist Organization and formed an alternative, the New Zionist Organization. They rejoined the ZO in 1946.

Religious Zionism

In the 1920s and 1930s, a small but vocal group of religious Jews began to develop the concept of Religious Zionism under such leaders as Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and his son, Rabbi Zevi Judah Kook. They saw great religious and traditional value in many of Zionism's ideals, while rejecting its anti-religious undertones. They were also motivated by a concern that growing secularization of Zionism and antagonism towards it from Orthodox Jews would lead to a schism in the Jewish people. As such, they sought to forge a branch of Orthodox Judaism which would properly embrace Zionism's positive ideals while also serving as a bridge between Orthodox and secular Jews. The movement also established several religious kibbutzim in Israel.

After the Six Day War, the Religious Zionism movement came to play a significant role in Israeli political life. It is a major component in the Israeli settler movement, although not all Religious Zionists support the settlements. Those who do often justify their attitude on the basis of the biblical promises of God to Abraham, in which the current Palestinian territories are described as belonging to Abraham's descendants through Isaac, and specifically not through the descendants of Ishmael (Genesis 21:12), through whom many Muslims trace their ancestry.

Critics of Zionism

There have been a number of critics of Zionism, including Jewish anti-Zionists, pro-Palestinian activists, academics, and politicians. Some of the most vocal critics of Zionism have been Arabs, many of whom view Israel as occupying Arab land. Such critics generally opposed Israel's creation in 1948, and continue to criticize the Zionist movement which underlies it. These critics view the changes in demographic balance which accompanied the creation of Israel, including the displacement of some 700,000 Arab refugees, and the accompanying violence, the inevitable consequences of Zionism and the concept of a Jewish State.

While most Jewish groups are pro-Zionist, some haredi Jewish communities (most vocally the Satmar Hasidim and the small Neturei Karta group), oppose Zionism on religious grounds and denounce all cooperation with Zionists. The primary haredi anti-Zionist work is Vayoel Moshe by Satmar Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum. Some other haredi groups support Israeli political parties which are also anti-Zionist but work through the political structure in order that their interests not be neglected.

The non-Zionist Israeli Canaanite movement led by poet Yonatan Ratosh, in the 1930s and 1940s, argued that "Israeli" should be a new pan-ethnic nationality. A related modern movement is known as post-Zionism, which asserts that Israel should abandon the concept of a Jewish state. Some critics of Zionism have accused it of racism, an accusation endorsed by the 1975 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379, which was revoked in 1991. There are also individual Jews who have taken strong public stands against various aspects of Israeli policy, but who resist the claim that they oppose Zionism itself. The most famous of is the linguist and left-wing political activist Noam Chomsky.

Christian Zionism

In addition to Jewish Zionists, a small number of Christian Zionists have been active from the early days of the Zionist movement. Throughout the entire nineteenth and early twentieth century, the return of the Jews to the Holy Land was widely supported by such eminent figures in the Christian world.

Evangelical Christians have a long history of supporting Zionism. Famous evangelical supporters of Israel include British Prime Ministers David Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Christian Zionism strengthened significantly after the 1967 Six-Day War, and many dispensationalist Christians, especially in the United States, now strongly support Zionism, seeing the establishment of the State of Israel as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gorny (1987), 5.

- ↑ Smith (2001), 1-12, 33-38.

- ↑ League of Nations Palestine Mandate, July 24, 1922.

- ↑ United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, Report to the General Assembly. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ↑ United Nations Special Committee on Palestine; Report the General, A/364, September 3, 1947.

- ↑ Youtube, Three minutes, 2000 years. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ↑ General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950, GA A/1367/Rev.1, October 23, 1950.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Almog, S., Jehuda Reinharz, and Anita Shapira. Zionism and Religion. Brandeis, 1998. ISBN 978-0874518825.

- Berkowitz, Michael. Nationalism, Zionism and Ethnic Mobilization of the Jews in 1900 and Beyond. Leiden: Brill, 2004. ISBN 9789004131842.

- Gorni, Yosef. Zionism and the Arabs, 1882-1948: A Study of Ideology. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987. ISBN 9780198227212.

- Rose, John. The Myths of Zionism. London: Pluto Press, 2004. ISBN 9780745320557.

- Shapiro, Yonathan. Leadership of the American Zionist Organization, 1897-1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971. ISBN 9780252001321.

- Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2001. ISBN 0312208286.

- Sofer, Sasson, and Dorothea Shefer-Vanson. Zionism and the Foundations of Israeli Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780521630122.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.